Stories of us: Rum rise and rapid fall of a Darlinghurst empire

Richard ‘China’ Jones went from one of colonial Sydney’s wealthiest men to bankrupt but still made his mark on one of Sydney’s most colourful ‘hoods.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If you stand on Kellett St in Potts Point today, you can see snippets of its centuries-old history — from its beginnings as an affluent hamlet for some of Sydney’s wealthiest residents in the early 1800s, to the tawdriness of the razor gangs in the 1920s and 30s.

Today Kellett St remains a product of its history with prestigious Victorian terraces, wine bars, cool cafes and stylish businesses existing alongside brothels and gentlemen’s bars.

Max Burns-McRuvie, the founder of Journey Walks whose company runs tours of Kings Cross focusing on Kellett St, said the street has almost come full circle from its colonial Sydney beginnings.

“It’s a real mix of all the different eras the street has experienced,” Burns-McRuvie said.

“Today it has more of a leafy, residential feel like when it was first established, but it also has remnants of the seedy element it experienced in the 1920s with a few brothels and a gentleman’s bar down one end.”

In the 19th century, what we know as Kellett St today was part of the area where wealthy businessmen built their mansions, up on the hill overlooking grimy Sydney town.

Allotments of land in this area, then known as Woolloomooloo Hill, were granted to cashed-up businessmen to create a feeling of wealth in Sydney.

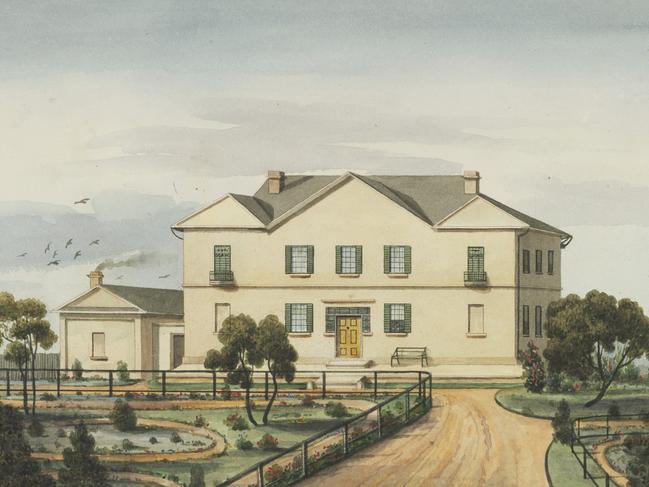

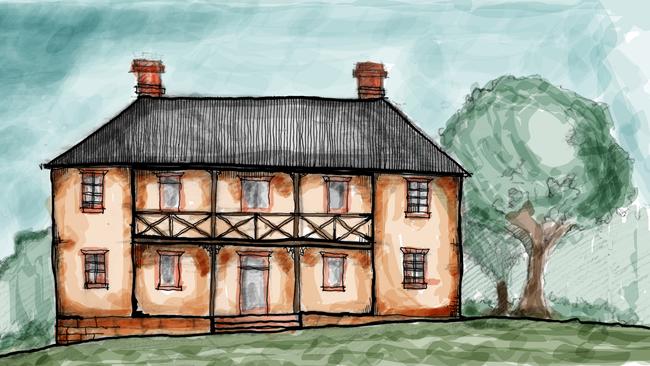

One of these grants was given to Sydney’s second surveyor and businessman, Samuel Augustus Perry, who built a mansion on modern day Kellett St in 1831 named Bona Vista, or beautiful view.

It was a two-storey Georgian sandstone structure surrounded by English gardens, which he sold three years later to wealthy merchant Richard “China” Jones nicknamed for his imports of tea and silk from the orient.

But it was his monopoly of the rum trade during the later years of Governor Macquarie’s rule that garnered a lot of Jones’ wealth.

From his mansion on the hill, Jones ran his empire, which at its height included part ownership in five whaling ships, 10,000 acres on the Hunter River where he grazed sheep he brought over from Saxony — revolutionising the Australian sheep industry — and dairy, pigs, poultry and a vineyard in Penrith, which in 1844 produced 10,000 litres of wine.

With his socialite wife, Mary Louisa, by his side they ran with the wealthy crowd in Sydney including their good friends Governor and Mrs Darling.

In the 1830s, Darling changed the name of the hilltop area to Darlinghurst and to cement the neighbourhood’s new name, the Jones’s changed the name of their mansion from Bona Vista to Darlinghurst House.

With the economic depression of the 1840s, a drought in Australia and the end of convict transportation, and hence free labour, Jones’s many business ventures failed.

“Jones lost all his holdings in the 1840s, sold all his ships, his property, including Darlinghurst House, and filed for bankruptcy in 1843,” Burns-McRuvie said.

“He went from being one of the wealthiest men in Sydney to having next to nothing in a very short span of time.”

The house was bought by Sir Stewart Alexander Donaldson, a business partner of Jones who went on to become the first premier of NSW. He changed the mansion’s name again, to Kellett House, giving rise in later years to the street name.

In 1877 the house was sold once again, to William Buchanan, a gold prospector, landholder and pastoralist, who demolished it.

In its place he built a row of six Victorian row houses called Bayswater Terraces, giving rise to an era of denser housing during which Kellett St lost its lush garden landscape.

The economic depression of the 1890s led to many of the old mansions in Potts Point to be subdivided and turned into cheap boarding houses, attracting a new demographic to the area.

In the 1920s the razor gangs roamed the streets of Potts Point, Darlinghurst, East Sydney and nearby Surry Hills with sly grog shops, brothels and illegal gambling run out of many of the old Victorian terraces.

Got a local history story to share? email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

ROUGH END TO A NOISY PARTY

In 1929 the Battle of Kellett Street raged where once well-heeled ladies had walked. Rival gangs associated with madams Tilly Devine and Kate Leight fought it out with pistols, razors, fists, rocks and bottles.

“On August 8, the rival gangs have a street party fuelled by alcohol and cocaine,” Burns-McRuvie said.

“A resident tells them to bugger off and the gangs turn on him. He lets off a warning shot from his revolver and it kicks the fighting off.” Amazingly, Burns-McRuvie adds, nobody died.

THE MARVELLOUS MRS JONES

A prominent merchant, land owner and pastoralist with political aspirations, Richard Jones needed a wife who could lift his place in society.

He arrived in Sydney in 1823 with his 18-year-old bride, Mary Louisa, and a decade later the pair moved into their new mansion on Kellett St. Mary Louisa, who was 18 years her husband’s junior, became a society lady chummy with Governor Darling’s wife, Lady Eliza.

She raised eight children and outlived her husband by more than 30 years, dying in 1887, aged 84.

SYDNEY’S NUDIST PIONEER NO STRANGER TO SCANDAL

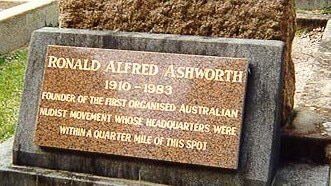

The residents of pretty and leafy Ashworth Ave in Belrose may not be aware of the link between their street’s name and a gravesite in the neighbouring Frenchs Forest Bushland Cemetery.

If they were to visit the final resting place of Ronald Alfred Ashworth they would discover their homes were built on or near land that was once Australia’s first long-term nudist club.

While the club was established in 1932 around Berowra in the Hornsby Shire, Ashworth later moved it to what is today Ashworth Ave, Belrose, with plans to build a clubhouse, pool, tennis courts and a miniature golf course for the club’s growing membership.

Local historian Beth Robertson says in the mid-1900s the area around Belrose and Frenchs Forest was remote bushland with little access and complete privacy — a perfect place for a nudist colony.

“I’m sure what attracted him to the area was that it was so isolated,” Robertson says.

“It was remote, beautiful bushland and perhaps the club members used the tracks to Frenchs Creek to swim.”

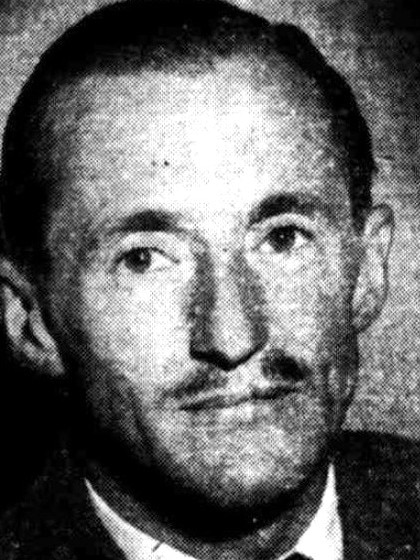

Ashworth was born in 1910 in Rockdale in Sydney’s south. He completed an apprenticeship as a mechanical fitter and later worked as an engineer. He married Ivy Hillard in 1938 and the pair settled in Balgowlah.

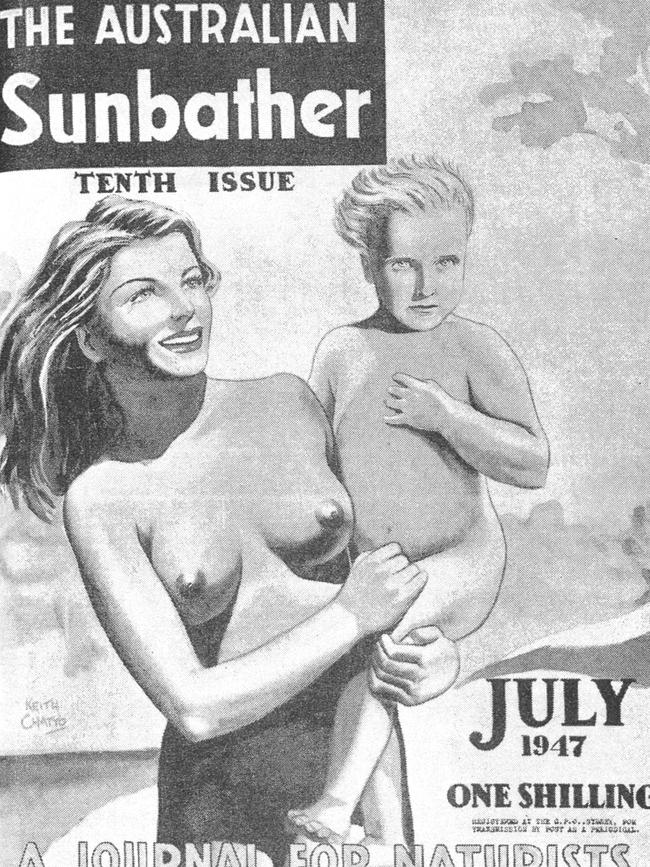

With club numbers growing, Ashworth launched Australia’s first nudist magazine, The Australian Sunbather, in 1946 and a year later bought the land at Belrose to accommodate the club’s growing membership.

On the weekend of November 13 and 14, 1948, an annual nudist convention was held at the Belrose property which Ashworth hoped would lead to a national body for nudists.

The weekend proved a great success with the formation of the Australian Sunbathing Association.

A tongue-in-cheek story ran in a local newspaper, reporting: “The fact that Sydney was experiencing one of its coldest weekends for some time did not deter nudists from all over Australia staging their first national convention.”

Nudists from Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and even New Zealand attended.

Ashworth was also a prolific publisher. In 1948, he launched The Australian Sunbathing Quarterly Review and in 1950 he published Naturism Illustrated, and at around the same time he brought out the magazine, Dare.

A story goes that the female staff at The Manly Daily newspaper, which in the mid-century also printed materials from business cards to magazines, refused to sell the magazine.

The growing membership also attracted disdain from the community and in December 1948 Ashworth defended his club in a local paper.

“We don’t want trouble with police, but we’d like an opportunity to show that we’re not breaking laws — written or unwritten,” he stated.

In the same article he claimed his club now had 600 members.

Despite his public protestations, Ashworth still managed several run-ins with the police and courts, the most notable in 1950 when he was caught in a hotel room with a married woman.

He faced court in the divorce proceedings that followed and was fined £100 and ordered to pay the husband’s legal fees.

The incident was captured in the satirical newspaper, The Truth, which called him the “apostle of nudism” and the “fresh air fiend”.

The article read: “(Ashworth) created a most embarrassing situation for himself when he set up his own after-dark nudist camp in a small hotel room with an attractive female convert to the cult as the only other member.”

He was also called before the court on charges of aiding and abetting the sale of an obscene article in 1948.

In 1952 he was not so lucky and was fined £5 for publishing obscene material in The Australian Sunbather, which included an image of a 12-year-old child. And in 1954 he was fined £20 under the obscene publications act.

In this same year, Ashworth closed his nudist club, his wife died and he largely disappeared from public view.

He died in 1983.

Got a local history story to share? email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

AUSSIE NUDISTS’ LONG WAIT

While public nudity has been around since ancient times – athletes participated nude in the ancient Olympic Games in Greece – the first official nudist clubs didn’t spring up until the early 1900s in Germany.

In Australia, nudists, or naturists as they prefer to be called, had to wait much longer for a nude swim in the ocean. In 1975, Maslin Beach in Adelaide became the first beach in Australia to legally allow nudists.

In Sydney, Lady Jane Beach at Watsons Bay became the state’s first ‘clothes optional’ beach in 1976 and since then many more have followed including Cobblers Beach and Obelisk Beach in Mosman.

FAMOUS NAMES LAID TO REST

The Frenchs Forest Bushland Cemetery recorded its first burial in 1940 and today has more than 25,000 burial plots.

Among them are some significant Australians, including yachtsman Ben Lexcen whose famed winged keel helped the Australia II to its breakthrough victory in the America’s Cup in 1983. Also buried there is writer and political commentator Bob Ellis, as well as poet Douglas Stewart.

The cemetery is also the final resting place of more than 1500 returned veterans.

However, only about 30 per cent of them have their military contribution inscribed on their memorial.

DAY WINDSOR RD REVEALED BURIED COLONIAL TREASURE

Anyone could have pulled back the grass on a spot by the side of Windsor Rd in Sydney’s northwest suburb of Beaumont Hills and discovered an important archaeological site.

Had you chosen the right spot, you would have found the sandstone and sandstock brick foundations of one of the area’s most popular colonial inns, as a group of archaeologists working for Transport NSW did in 2013.

The group, led by planning and environmental consultancy group, EMM, were doing a test excavation as part of an early works program for the Sydney Metro Northwest Project when they pulled back the grass and, just below it, found the foundations of the White Hart Inn.

They didn’t know it at the time, but the inn was one of the most popular on the road between Parramatta and Windsor, a respite for weary passengers undertaking the arduous road trip in the early to mid-1800s.

While the test excavation found the footings of a two-storey Georgian property which would have had a veranda at the front, a wing room off either side, a detached kitchen at the rear and a cistern out back, the site was again carefully covered up and preserved for future archaeologists. The further protection of a state heritage order was granted in 2016.

As a result, Transport NSW redesigned the sky rail that would pass over the site and shifted away a pier that was initially designed to plunge right through the heart of the inn.

The White Hart Inn was built about 1827 by pardoned convict James Gough who also built properties of significance in Windsor and Sydney, and on land owned by the principal magistrate of the Hawkesbury, William Cox.

Gough became the Inn’s first licensed publican, but many other publicans followed, including Sarah Tighe, whose husband John Booth was the publican at the nearby Royal Oak Inn, which we today know as the Mean Fiddler.

When the White Hart Inn opened, the Sydney Gazette stated it was “fine and noble looking”.

Pamela Kottaras, historic archaeologist for EMM, says the find was of local and state importance due to the involvement of renowned convict builder, James Gough, the early period it dates from and the fact so much of it survives.

Artefacts such as coins dating from 1816, pharmaceutical and perfume bottles, a clay smoking pipe, buttons and a near-intact ceramic toothpaste container were also found.

“Wherever there are new roads, you’ll find inns because they served a very important function of providing food and lodging for travellers on the road,” Kottaras says.

“A few kilometres down the road there was the Box Hill Inn, which today stands in ruins, and the Royal Oak, or Mean Fiddler also nearby. All these inns would have been direct competitors in the mid-1800s. But the important thing to note here is that these inns weren’t used for holidays, they were a necessary stop on a long and difficult road journey.”

Kottaras adds that when the railway line from Sydney to Richmond was constructed in 1864 and a stop to Windsor added shortly after, the use for inns slowly disappeared.

Many became family homes, as did the White Hart Inn when the Bryan family bought it at auction in 1881. Little more is known of the inn after this date, but at some stage around the late 1800s or turn of the century it was abandoned.

“The interest in sites like this is not so much in the bricks and mortar, but in the stories they reveal about the people that lived there and the communities they serviced,” Kottaras says.

“We had a three-day event in 2014 to share with the community what had been unearthed. People were brought in by coach and there was a person speaking about the artefacts that were found, and archaeologists who worked on the site showed people around.

“There was immense interest from the community.”

Got a historical story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

FROM ROYAL OAK TO MEAN FIDDLER

The Royal Oak Inn was built in 1929 on the corner of Windsor Rd and what would later become Commercial Rd. It was passed through several different owners and even used as a private home from 1916 to 1925 but was revived as a restaurant in 1947.

In the 1960s, after renovations, it operated as The Royal Oak Inn restaurant and over the years was extensively extended and renovated, even adding a wedding venue.

In 1996, it was renamed The Mean Fiddler but in an effort to erase its once notorious rough profile, it again changed its name in 2014 to The Fiddler.

KELLYVILLE’S CONVICT PAST

The land where the White Hart Inn once stood is today known as the suburb of Beaumont Hills. But before that modern-day suburb was founded in 2002, it was part of greater Kellyville.

It is believed Kellyville was named after Hugh Kelly, who arrived in Australia from Ireland as a convict in 1803 but was later given a land grant in Sydney’s northwest. It is said Kellyville was once nicknamed ‘There and Nowhere’ as it was on the road from Parramatta to Windsor, as well as ‘Irish Town’ for its predominantly Irish residents.

CRITICS CIRCLED WHEN FRIDGE KING MADE HAY FOR TARONGA

The only thing that remains of the once-impressive Taronga Zoo Farm in Mona Vale is a tarnished bronze plaque, hidden among the chaos of busy modern suburbia.

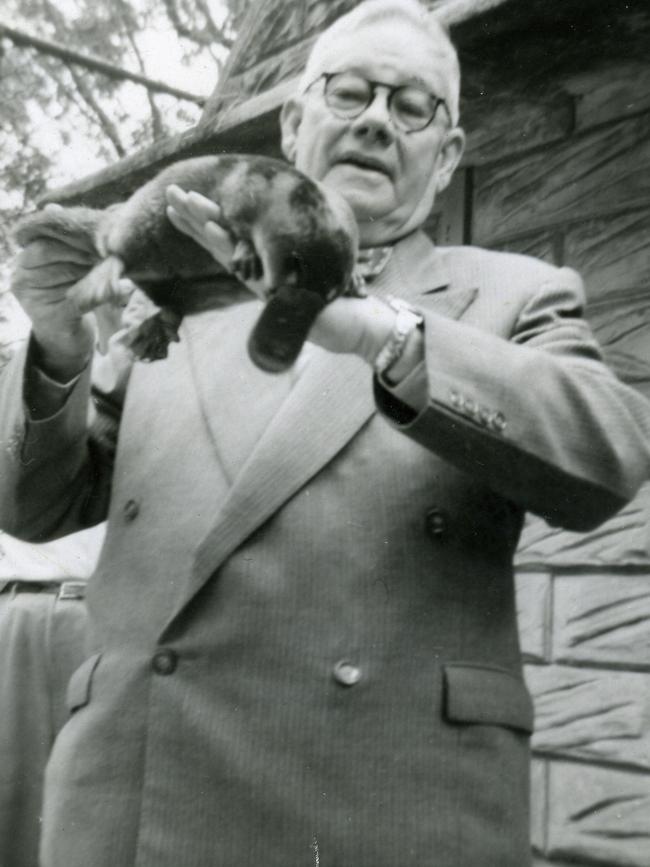

It tells the story of Edward Hallstrom, who in 1947 bought a 40-acre block in the northern beaches suburb and established the Taronga Zoo Farm and koala sanctuary.

Today the site is mostly occupied by the Aveo Bayview Gardens retirement village.

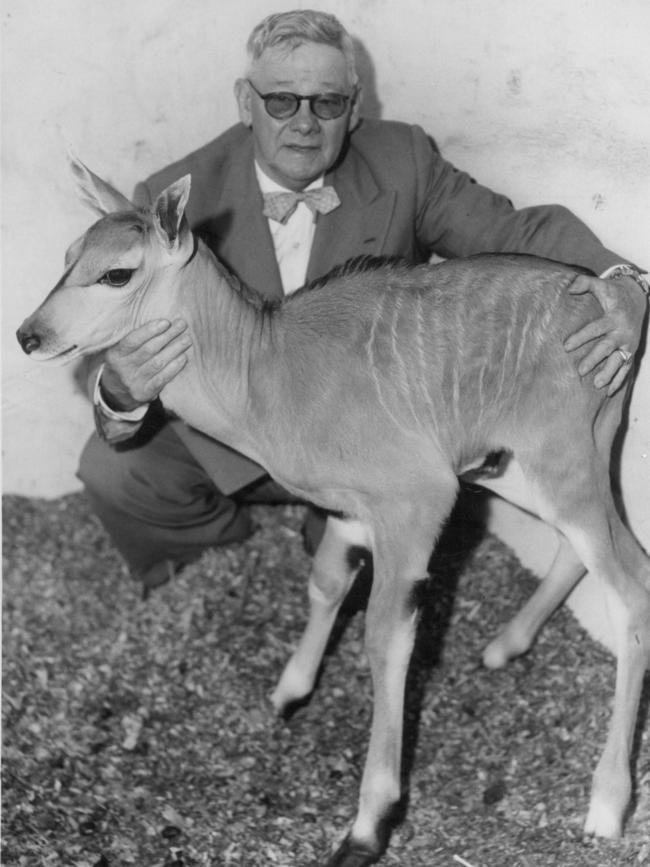

Edward Hallstrom was born near Coonamble in 1886, the second-youngest of nine children.

When he was four, his father’s farm collapsed and the big family moved to the inner-west Sydney suburb of Waterloo.

While his early childhood was challenging – his parents’ divorce forced 10-year-old Edward to contribute to the family income with odd jobs – he fostered a love of animals from an early age and is said to have had pets which included dogs, white mice, guinea pigs, cats, rabbits, parrots and other birds.

Although Hallstrom left school at 13, he was a keen businessman and inventor, making his money in refrigeration.

In the backyard of the family’s Dee Why home in 1923, Hallstrom invented the Icy Ball absorption refrigerator and later the Silent Knight Upright Refrigerator which became a popular domestic product in the 1940s.

The Australian National University’s Australian Dictionary of Biography states his company was producing 1200 Silent Knight refrigerators a week by the mid-1940s.

With the proceeds of his refrigeration company, Hallstrom donated two rhinoceroses to Taronga Park Zoo in 1937, establishing a long partnership with the Sydney zoo and in 1941 he was appointed a trustee.

He would later hold the positions of vice-chairman and president.

Wanting to provide the animals with a fresh food source close to the zoo’s Mosman location, Hallstrom established the Taronga Zoo Farm on a 40-acre block at the back of Mona Vale. The site also became home to Hallstrom’s own private animal collection which included many birds, albino kangaroos and two sets of twin white wallabies.

He also established a koala sanctuary there and, with the help of a veterinarian, treated sick and injured koalas. The sanctuary would later develop a breeding program and was used for research into the conservation of koalas.

While he was largely considered a generous philanthropist and dedicated animal lover, Hallstrom came under attack for his work with the zoo and was quoted in a local paper defending the captivity of animals in 1951.

“In many ways zoo animals are lucky, kept in reserves as at Taronga Park,” he said.

“They are assured of good food, expert veterinary attention and complete freedom from fear of death from their natural enemies.”

His involvement in sending two koalas to the US to appear in the Hollywood film Botany Bay, in the 1950s, was also criticised.

He had a special permit from the state government allowing the transfer of the koalas as export of these animals had been banned since the 1920s.

They were later homed in the San Diego Zoo and other koalas were sent to a zoo in San Francisco, making them the only animal parks at the time to have koalas in captivity outside Australia.

Hallstrom’s philanthropy – he is believed to have donated about $4m to medical research and hospitals as well as Taronga Zoo – attracted a knighthood in 1952, but soon after two state government inquiries criticised his lack of professional skills as a zoologist.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography states he even came under court surveillance for the illegal trafficking of fauna in 1966, though he was never charged.

Around this time, food produced at his Mona Vale farm was found to be deficient in vitamin E and the lucerne too rich for the animals, so Western Plains Zoo took over hay production for Taronga Zoo.

Hallstrom’s Zoo Farm was subdivided and sold from 1976.

Hallstrom donated his entire personal collection of animals to Taronga Zoo in 1968 and two years later he died at his Northbridge home.

* Got a local history to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

TARONGA’S BEST BUT NOT FIRST

Although Taronga Zoo is heralded around the world as one of the best animal parks, it was not the first to open in Sydney. That honour goes to a public zoo created at Moore Park on a site known as Billy Goat Swamp. Inspired by the bar-less animal exhibits at the Hamburg Zoo on a trip in 1908, the zoo secretary proposed a new site be sought for Sydney’s public zoo and the state government granted a site north of the Harbour. Taronga Park Zoo opened in 1916 with the landmark top entrance, the seal ponds, elephant temple and monkey pits established.

BEACHSIDE SUBURB’S MANY NAMES

The origins of Mona Vale’s name are often disputed. It is commonly accepted that Mona Vale was named by one of its earliest settlers, Robert Campbell, in honour of a town in his Scottish homeland. However, Pittwater Online News reports the suburb has been known by several names, including Turimetta after a local

Indigenous clan. They state Turimetta Village was used by locals to refer to the centre of Mona Vale as late as the 1960s. It was also known as Rock Lily, for the large amounts of that flower found in the area.

MORE STORIES

Paddington’s first picture show no picnic for patrons

Frugal life and lonely death of Australia’s first millionaire