Australian WWI diggers went from battlefield horrors to victory in 1919 Peace Regatta

One minute the men were fighting for their lives in the blasted battlefields of World War I. Th e next they were rowing to victory between the soft green banks of the River Thames

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Even for this fit and enduring group of returning Australian soldiers, the shock of place must have been shattering.

One minute they were fighting for their lives in the stinking trenches and blasted battlefields of World War I. The next they were rowing an elegant, eight-oar racing scull to victory between the soft green banks of the pretty River Thames at Henley.

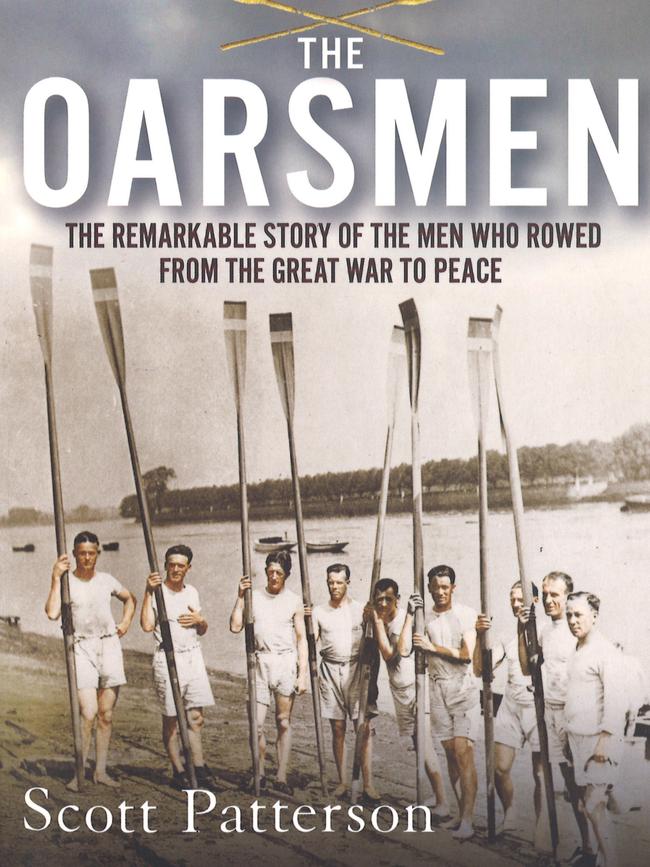

The extraordinary story of the 1919 Royal Henley Peace Regatta is told in The Oarsmen, author and filmmaker Scott Patterson’s new book to be launched in Sydney on Thursday.

The book, published by Hardie Grant Books, begins with Private Thomas Whyte who, having rowed regularly for South Australia, was manning the oars on one of the vessels taking troops to shore at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. Hours before, Whyte had written: “Personally, I feel exactly like I used to on the morning of an important boat race”. It was to be the last race of his life. Shot through the pelvis by a Turkish sniper as he rowed for the beach, Whyte bled out and died the same day. Arthur Blackburn, an old school friend, wrote to Whyte’s fiance that her beloved had been joking and laughing all the way to the pre-dawn shore before being shot.

Fit and adventurous and highly disciplined in teamwork, Australian oarsmen had volunteered for the war in large numbers. Syd Middleton, who would play a leading role in the Peace Regatta, was one of them. Born in 1884 in Pyrmont, he was big and tall with “natural competitive aggression”. He had rowed in the 1912 Henley Royal Regatta Grand Challenge Cup and the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. A clerk at the AMP Society, Middleton enlisted with the AIF on May 5, 1915 and arrived at Gallipoli in August.

Another 1912 Olympian, Henry “Harry” Hauenstein of Macdonaldtown, Sydney, had also joined up. On the day of his enlistment, he married Eva Loaney at St Stephen’s Church, Newtown. Hauenstein was “a giant of a man, fond of a drink, loyal to his friends, terrifying to his enemies”. He served on the Western Front and was awarded the Military Medal for bravery.

Among other rowers who distinguished themselves in the war were men who would ultimately row to victory in the AIF No. 1 boat in the Henley Peace Regatta — they were Archie Robb, Fred House, George Mettam, Arthur Scott, Tom McGill and Clive Disher with Albert Smedley as coxswain. Hauenstein and Middleton were also in the No 1. team.

The Peace Regatta came about when military authorities needed a plan at the end of the war to ameliorate frustration among the 200,000 Australian soldiers awaiting repatriation. Sport was the answer, and the military brass “began to comb the ranks of the Australian armed forces for talented sportsmen who could spearhead this ambitious reworking of martial arts aggression into good-natured sportsmanship”.

Middleton, whose reputation as a sportsman was huge and who was awarded a DSO in 1919, was put in charge. While already suffering from the shell shock and depression that would dog him for years to come, Middleton organised a squad of Australian rowers to compete at the Valhalla of rowing, Henley on Thames.

On July 5, 1919, after only a couple of months of training and amid a sea of spectators including “English roses beautifully decked out with flower-adorned wide-brimmed hats and their prettiest dresses”, the Australians rowed to victory for the coveted King’s Cup.

“As the AIF No. 1 crew neared 100 yards from the finish line, one length clear of Oxford, the roar from the diggers was deafening,” Patterson writes. “The AIF No. 1 crew crossed the finish line in a fast 7 minutes 7 seconds — the fastest time recorded for the eights throughout the whole of the Royal Henley Peace Regatta.”

On the riverbank, men who had lost their legs in war were lifted out of their wheelchairs for a view of the victors.

Disher described the rejoicing that met him as he climbed out of the boat at race’s end: “The ‘digger’ of whom there seemed to be hundreds nearly went mad. General Hobbs the Corps Commander almost cried down my neck and barely had voice to tell me he was the happiest man this side of the world”.

Princess Arthur of Connaught presented the King’s Cup to the Australians. For the oarsmen of Henley, who would soon return to their homes and their jobs, it was a sweet victory after the much bigger contest they had just survived.