The international music world pauses to reflect on composer Leonard Bernstein’s centenary

BERLIN on Christmas morning 1989 was bright and sunny. Outside the city’s grand old concert hall, the Schauspielhaus, hundreds of people packed the square.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BERLIN on Christmas morning 1989 was bright and sunny. Outside the city’s grand old concert hall, the Schauspielhaus, hundreds of people packed the square.

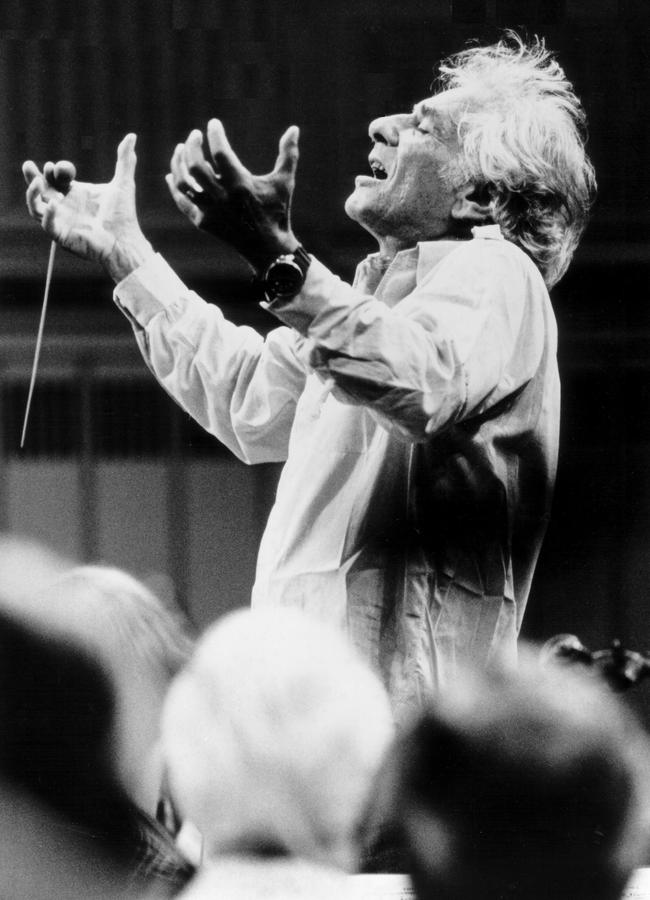

Inside, an audience sat spellbound as Leonard Bernstein, 71, conducted The Ode To Freedom Concert.

It was indeed the first free Christmas in Berlin since the infamous Berlin Wall had been thrown up overnight in 1961, dividing the city. The Wall had fallen just weeks before Bernstein took up his baton.

Just as the world had watched the Wall come down in chunks, 100 million people around the world tuned in as Bernstein led the orchestra, choirs and soloists at the Schauspielhaus.

For the big event, Bernstein chose Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which was long associated with freedom and peace. He made just one adjustment to Beethoven’s masterwork. When the libretto called for the word “joy” to be sung, Bernstein substituted the word “freedom”.

At the end of the symphony, the audience’s standing ovation looked as though it would never end. Bouquet after bouquet were brought to Bernstein on the podium. Elated, the conductor threw some of them into the midst of his orchestra, causing the entire audience to laugh and to clap even louder.

Leonard Bernstein would later describe that Christmas concert as truly unforgettable.

“I am experiencing a historical moment, incomparable with others in my long, long life,” Bernstein wrote.

After the concert, Bernstein went to the Berlin Wall. Borrowing a little boy’s chisel, he chipped off some fragments to take home to New York.

He would not live to enjoy his souvenirs for long.

On October 14 of the following year, Bernstein died from cardiac arrest brought on by side-effects of treatment for mesothelioma.

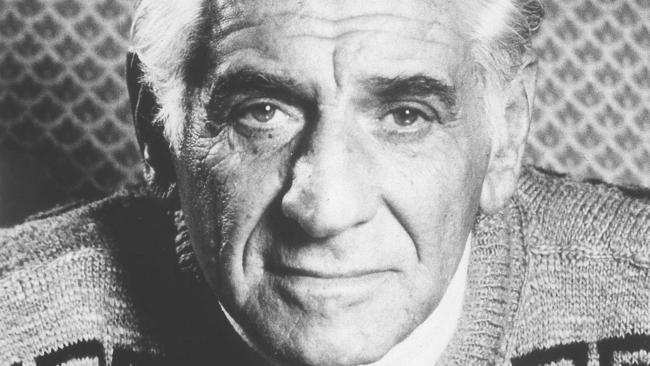

Today, on what would have been his 100th birthday, the musical and humanitarian worlds are pausing to reflect on Berstein’s legacy as pianist, conductor, composer and humanitarian.

Leonard Bernstein is closely aligned with New York City. He lived in the Dakota Building on Central Park and his most famous work, West Side Story, is set in the city.

But he was actually born in Massachusetts, where his parents fostered his early love of piano.

He studied at Harvard, where he met composer Aaron Copland. Bernstein would later call Copland his only real composition teacher. After further study in Philadelphia, Bernstein moved to New York.

In 1943, while working as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, the 25-year-old stood in for guest conductor Bruno Walter, who was ill, and made a triumph.

“I strode out and I don’t remember a thing from that moment — I don’t even remember the intermission — until the sound of people standing and cheering and clapping,” Bernstein said.

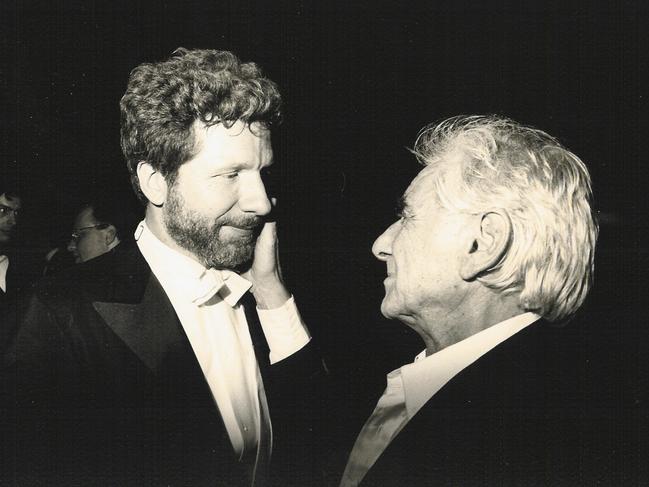

He met choreographer Jerome Robbins, with whom Bernstein collaborated on the ballets Dybbuk and Facsimile and the musicals West Side Story and On The Town.

“The one thing about Lenny’s music which was so tremendously important was that there always was a kinetic motor,” Robbins said. “There was a power in the rhythms of his work which had a need for it to be demonstrated by dance.”

Bernstein was becoming, as conductor John Mauceri said, “the iconic voice” of his age.

In 1951 Bernstein had married Felicia Cohn Montealegre, a Chilean-born American actor with whom he had children Jamie, Alexander and Nina. Bernstein was also a homosexual, as revealed in a book published several years ago.

Meanwhile, the plaudits flowed. In 1953 Bernstein became the first American to conduct at La Scala in Milan. He composed the music for Marlon Brando’s classic 1954 film On The Waterfront, which cleaned up at the Oscars.

In 1959 he conducted the New York Philharmonic’s first tour to the then USSR, and at the 1961 pre-inaugural gala for President John F. Kennedy.

Bernstein was never a music snob. He loved all kinds of music, including The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and African music.

And he adored the visual arts, finding the playfulness of Picasso’s work particularly inspirational.

Bernstein’s 100th birthday marks the halfway point in an official, two-year celebration of his life involving at least 2000 events around the world.

But for his son Jamie, it was the Berlin Christmas concert that best reflected Bernstein’s biggest hope — “that if enough hearts would open themselves to the beauty of great music, there would be no room left in any of those hearts for evil, greed or hate”.