The Cold War came to Bentleigh East when defecting KGB spies moved to the ‘burbs

The arrival of two defecting Soviet spies in a nondescript street in suburban Melbourne was officially strictly hush-hush. So naturally, it was Bentleigh East’s worst-kept secret.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s not much to look at from the street, and apparently it’s hardly changed in more than 60 years — but this brick veneer pile in Bentleigh East was a part of Australia’s most dramatic Cold War incident, the Petrov Affair.

Vladimir Petrov was third secretary at the Soviet Embassy in Canberra, but there was more to Petrov and his wife Evdokia that met the eye.

Both were experienced KGB spies, sent to Australia in 1951 to help establish a Soviet spy network.

After their dramatic defection the couple was given new identities and went on to live quietly in Melbourne, working local jobs but living a largely solitary existence. But the fear of retribution didn’t leave them for decades.

How the Petrovs came to defect

A Russian-speaking Polish man Dr Michael Bialoguski, a violinist, musical arranger and part-time ASIO operative, was tasked with convincing Mr Petrov to defect.

Bialoguski plied Petrov with booze and women, including sex workers, at his unit in Sydney as their relationship built. ASIO kept watch and searched Petrov’s brief case as he lolled unconscious after drinking.

A new Soviet ambassador was appointed to Canberra in 1953, following the death of dictator Joseph Stalin.

The Petrovs found themselves on the outer at the embassy, accused of being sympathisers of a rival faction in the Communist Party, and were ordered to return to Russia and a potentially very bleak future by April 1954.

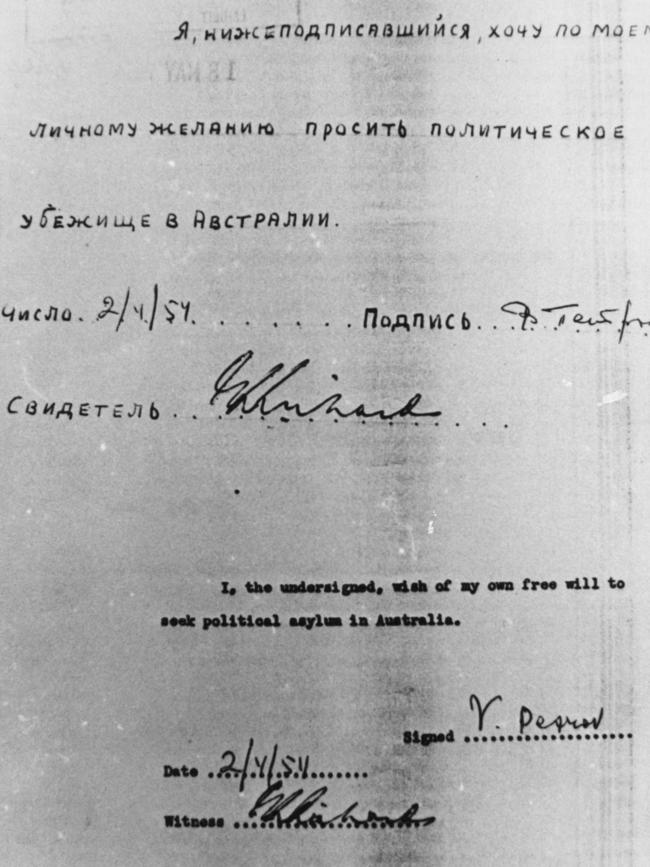

ASIO pounced, approaching Petrov to defect in February 1954.

After a few weeks of negotiations, he became ASIO’s greatest Cold War prize and he went immediately into ASIO’s protection.

The trouble was, Mr Petrov did not tell Mrs Petrov what he was up to.

The Soviets held Mrs Petrov and Mr Petrov’s dog, Jack, under house arrest at the embassy and told her that her husband was dead.

Two KGB agents were dispatched to Australia to repatriate her to Moscow.

The agents towered over the slight Mrs Petrov as they dragged her through Sydney Airport to a waiting BOAC flight on April 19, 1954.

Mrs Petrov lost her shoe as she resisted the agents and an angry mob including many Russian refugees swarmed in an effort to rescue her.

The images shocked Australians and were flashed to newspapers around the world.

The prime minister, Robert Menzies, ordered ASIO to intercept the flight when it refuelled in Darwin to offer Mrs Petrov asylum.

The ASIO agents disarmed the KGB officials and escorted Mrs Petrov from the plane.

After speaking to her husband on the phone, and 15 minutes before takeoff, Mrs Petrov accepted, and was reunited with her husband in Sydney.

ASIO even retrieved Jack from the embassy and returned him to the couple.

Their defection and fears of communist infiltration in Australia and the Labor Party gave the Menzies government a big victory in the 1954 election.

A subsequent royal commission into espionage in Australia led to the split in the ALP that saw the creation of the Democratic Labor Party, which kept the ALP out of office federally until 1972.

The Petrovs and their new life in Australia

The couple was given new identities, Sven and Maria Anna Allyson.

The couple was shifted to a series of ASIO safe houses including one at Sandringham and others in Sydney’s Palm Beach and Leura, near Katoomba in the Blue Mountains.

Both were questioned extensively by their ASIO minders and officers from agencies including the CIA and MI5.

Mr Petrov outranked his wife in the KGB — a colonel to her captain — but her expertise with KGB codes proved more useful to ASIO.

Their information led to the exposure of 600 Soviet spies around the world ensuring they would never again see the USSR, and a book based on those conversations, Empire of Fear, was ghostwritten by an agent close to the pair, Michael Thwaites. The book was later denounced by Mrs Petrov as a pack of lies.

The couple received a £5000 payment — about $160,000 today — for their service to the Commonwealth of Australia, a pension and the royalties from the book.

They moved to Melbourne in 1956 with enough money to buy an unassuming house in Parkmore Rd, Bentleigh East.

Jenny and Kerry Honey moved next door to the Allysons in 1962.

The Honeys became close to Sven and Maria Anna, who was known as Anna.

“It hasn’t changed,” Ms Honey said of the old Petrov house.

“We came here in 1962. It was very funny because we hardly knew anything about the Petrov thing.

“But the minute we came in the people up the street told us, “Do you know who your next door neighbours are?”.

Sven and Anna’s life was a largely solitary one.

The couple had few friends beyond the ring of ASIO agents that watched over them and, at times, their marriage was strained by Sven’s hard drinking and depression and the constant fear for their lives.

In its history of the Petrov Affair, the Museum of Australian democracy said Sven expressed his distress in 1967: “No friends, no future. I wish I was dead. No-one could dream of our misery.”

Years of looking over their shoulders

Anna, who had to deal with the knowledge of her husband’s extra-curricular activities before his defection, was cut off from her family.

Her loved ones at home were persecuted for the defection. Her father lost his state-sponsored job and, Ms Honey said, and her younger sister Tamara’s future was marred by the defection.

“Tamara had a very tough time when they defected. She was a lot younger than Anna. She was to go to university, and she got told she couldn’t go. Anna said it (the defection) was like a death. I felt very sorry for them.”

The Red Cross reconnected the family in 1960. Only then did Anna find her father had died three years earlier.

She corresponded with her mother until her death in 1965 and she remained in touch with Tamara until she emigrated to Australia in 1990 as the Soviet Union collapsed.

The couple looked over their shoulders for decades.

A quiet suburban life was no guarantee they’d be safe from the Soviets.

The constant threat to their very existence revealed a steely resolve in Anna, Mrs Honey said.

“She was much tougher than him, and I mean really tough, and she was smart. Smart as a cookie.

“He was a colonel and she was a captain in the KGB, but she was smarter — and you wouldn’t want to cross her.

“And he was a heavy drinker.

“They were frightened. She would never leave Australia

“You wouldn’t want to live like that. Horrible. We’ve got it easy. I’d hate to live in fear like that.”

Mr Honey said he felt for Sven and Anna.

“They were going to be killed if they went back, and they were petrified that it was going to happen here. It was a hell of a lonely life,” he said.

Sven found work developing film at Ilford Photographics in the Waverley area.

Developing film was a skill he used in his spy days. He developed film sent from Moscow to receive his instructions from the KGB.

Anna was for a time a typist.

Later, she worked at a company that made data entry cards for early computers.

Mr Honey said Anna worked well into her 60s.

HOW A TOWN SAVED A LOST AIRLINER

Tales of Sven’s drinking were legendary, the Honeys said.

One neighbour spoke of an occasion when Sven, drunk and depressed, fell over the front fence and smashed his head on the footpath on the other side.

Mr Honey remembered the time Sven’s dog Butch, known for his aggression, escaped the yard. A drunken Sven, looking for Butch, stumbled into a neighbour’s driveway and stopped to chat.

”Joe was washing his car and Sven came in. He was very drunk. He was leaning on the car and he just slipped down and fell on the ground,” he said.

“And one time, he crashed his car into a fence up the street. The ASIO people were here within a very short space of time because he rang straight up. No charges were ever laid.

“Yeah, he drunk a lot of grog in his time.”

Mr Honey said ASIO agents were a regular presence in the neighbourhood.

“We were pretty close to the ASIO guys in the end. Most of the top guys in Victoria. They were great to them. They were in contact every week.”

Mrs Honey added: “They were great. It took the pressure off us.”

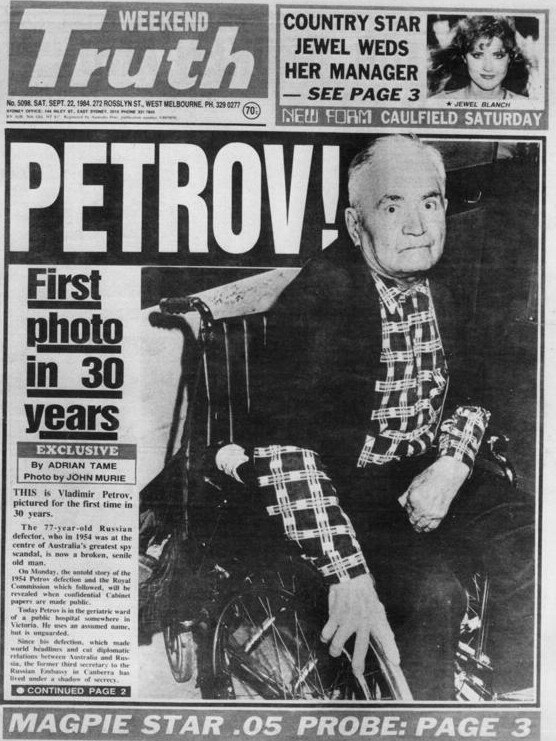

Sven suffered a series of strokes in the mid-1970s and was forced to live for the rest of his life at the Mount Royal Hospital in Parkville. Anna visited him at least once a week.

The whereabouts of the former Petrovs was the subject of a rare D-notice, or Defence Notice, which banned the publication of any details relating to the couple’s new assumed life.

Their cover was blown in 1982

A horde of reporters, photographers and news crews descended on the quiet street.

“When it all became public, it was just awful,” Mrs Honey said.

“ASIO even cut a gate through their back fence so that Anna could get in and out of the house. It was really, really bad.,” she said.

“There was a man from one of the Channel Two programs. He was desperate to get an interview with Anna. He would leave flowers on the porch, and Anna would just leave them there until they died.”

“ASIO was very good to them, really looked after them. They were lovely people, most of the ASIO people.”

Sven died at Mount Royal Hospital from pneumonia, aged 84, in June 1991, the year after Tamara came to live with Anna in Melbourne.

“Apart from one friend of Anna’s and us, it was all ASIO people at his funeral,” he said.

Anna died in July 2002, aged 87.

Tamara inherited the home, and sold up in 2009.

The current owner, Fiona Ye, laughed when the Herald Sun told her of the house’s Cold War history.

“I had no idea,” she said.

She said she bought the house from Tamara in 2009.

“She said Melbourne is not cold enough, so she went back to Russia,” Ms Ye said.

“She went to live with her son.

“She was a very nice person, I think. After we bought this house she asked us to come in and have champagne with the neighbours to celebrate. It was nice.”

MORE: AMPUTEE GANG TERRORISED OLD MELBOURNE

HIP INNER CITY SUBURBS ONCE MELBOURNE”S SLUMS

SOUTHERN CROSS HOTEL” MELBOURNE’S STAR MAGNET

Those neighbours included Kerry and Jenny Honey.

Mr Honey said he was pleased to discuss Anna and Sven again.

“One upon a time, it was a big topic of conversation around here,” he laughed.

Originally published as The Cold War came to Bentleigh East when defecting KGB spies moved to the ‘burbs