QWeekend: Meet the identical twinnies Paula and Bridgette Powers who’ve shocked the world

They’re the viral sensations who literally have everything in common - but just who are the identical twins the world is talking about? In 2006, we sat down with the pair for an exclusive chat.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They’ve become the most talked about twins globally after an iconic interview where they spoke in unison and completed each other’s sentences.

While Sunshine Coast pair Bridgette and Paula Powers are well-known in Queensland, the Twinnies have gone viral across the world.

The identical Twinnies stole the limelight in an interview that occurred just moments away from a crime scene that rocked South East Queensland on Monday in a carjacking rampage on the Bruce Highway.

The interview followed a horrific six-car pileup on the Bruce where a woman was killed and a man allegedly shot.

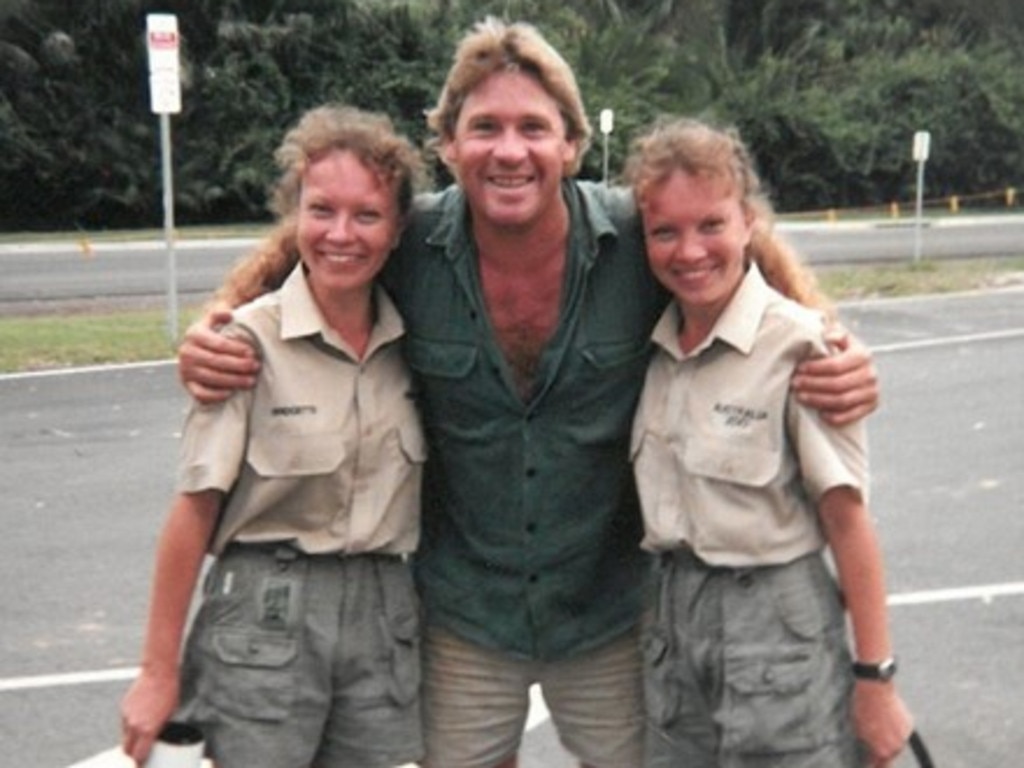

The Twinnies were mentored by the late Steve Irwin and are no strangers to going viral, having appeared in unison in an interview with Piers Morgan on Good Morning Britain.

But who exactly are the Twinnies, why do they speak as they do and why do they love pelicans so much?

Back in 2006, The Courier-Mail’s Leisa Scott sat down with the pair for a QWeekend exclusive with the Twinnies.

You can read it below.

What do Bridgette and Paula Powers have in common? Well, everything - including a mission to save stricken seabirds, and the powers of endurance to crisscross and circle the country, on foot and by bike.

Pelecanus conspicillatus (Australian pelican):

Found throughout Australia, this big-billed bird with the large throat pouch weighs up to 6.5 kilograms and has a wingspan reaching three metres.

Can live beyond 50 years in captivity, eats mainly fish, but has been known to drown seagulls for food. Can soar up to 3000m on thermals.

Monozygotic powers (the Powers twins):

Located in the Sunshine Coast hinterland, these identical twin sisters travel far and wide rescuing pelicans and other seabirds. Now 32, they are vegetarians with an uncanny ability to second-guess each other. They are full of surprises.

To watch these two natural wonders interact, our journey takes us to a lowset brick home on an average-sized block in Beerwah, on the doorstep of the Glasshouse Mountains. There are two small cars and a minimalist garden out front - a picture of suburban conventionality.

Until the door is answered.

There stand Bridgette and Paula Powers, looking sporty in matching outfits of candy-striped blouses teamed with corduroy knickerbockers. They smile broadly and say hello in small, sing-song voices, before escorting us past their dad, John, and his computer game, and onto the back patio.

Gliding past numerous domestic birds in cages, the curly-haired blondes head towards the little pond with the tiny moat which their mum, Helen, always intended as a simple water feature. That was never going to happen with her Storm Girls around. Gemma, a swan who did battle with an eel and came off second best, lives there now.

Cinnamon, the wood duck, waddles past with his damaged wing. The twins give him a “Hello, darling” and continue towards the back of the yard where Meredith, Tash and Mr Percival are waiting. The stroppy Mr Percival is in his own enclosure with a wayward brown booby, but the two female pelicans are free to wander around as much as they like.

“This is Meredith,” starts Paula, “she’s got a damaged hip and needs a lot of physio.” It’s a very unsettling story. Not the injury so much; these things happen in the wild and she’s safe now. It’s more the delivery of the story, the entire sentence coming out in stereo but slightly delayed, like an echo. By the time Paula - at least I think it’s Paula - mentions Meredith’s name, Bridgette, too, is telling the story. In the exact same words.

“Oh, people always say that,” they say, breaking into a high-pitched, drawn-out giggle when asked about their speech patterns. “We don’t even know we’re doing it.” Dressing alike, though, is done consciously, and despite Helen’s attempts to get the petite women to at least wear different blouses. They share a bedroom, like the same music, movies and food. A doctor has told them their heartbeats are exactly in time, “like looking at the same heart”.

They embrace their sameness. Tell most twins they are indistinguishable, and they’ll do a song and dance to show their individuality. Not these two. Go one step further and tell them they really are one person, and they happily agree: “Yes, yes, we are,” they say in unison. “We have a special bond.” Which works a treat for the pelicans. Unable to work apart from each other - they tried that once at Steve Irwin’s Australia Zoo - the twins have channelled their love of wildlife into rescuing seabirds. “Not too many people look after seabirds - probably because they’re smelly and have got lice and can cost a lot of money. But we weren’t frightened about touching them, or getting dirty or fishy.” In fact, being a duo makes them formidable on a rescue mission. Bridgette acts as the forward party, dangling a fish before the wounded or ill pelican until it moves to take it. Once it has the bait, Bridgette quickly hooks her finger into the bird’s pouch as Paula, lurking behind, “gives him a big bear hug”.

Of course, in the meantime, the bird is gnawing on Bridgette’s arm but, they chorus, “when you look into their eyes, wow”. They giggle some more and add, “We call them love bites.” Helen, grinning, calls out from the patio where she’s cleaning windows:

“It’s lovely having a pelican as a son-in-law.”

Some stories are straight forward pointing, you right to the source, no deviation necessary. Others lead you down the garden path to a stinking mess.

And some start out heading in one direction only to contort and bend like a country lane before dropping you off somewhere completely unexpected.

This began as a story about pelicans. Just a look at the big bird of the sea, that fascinating aerodynamic masterpiece which can skim the surface of the ocean by centimetres or soar into the sky like a fat-bellied glider. Along the way, some questions were answered.

Do coastal birds really head west with the big rains?

That’s more romance than fact, say the experts. Many pelicans are coastal dwellers with colonies in secluded areas near the coast - a Lake Eyre sojourn for a coastal Queensland bird is possible but largely unnecessary and unlikely. Why do you never see a baby pelican?

They grow to about full size in 70 days and hang around the rookeries for a few months, but juvenile birds can be recognised by their brown, not black, feathers and pale, not grey, feet. Why do they sit on the lights above Redcliffe’s Houghton Highway and crap on your windscreen, causing a momentary and hair-raising “white out”? Just for laughs.

At least, that seems as good a reason as any among the crowd which gathers at Redcliffe’s Pelican Park to watch the birds being “checked”.

Every day at 10am, a little bit of fish in a bucket encourages them down off their perches, giving volunteers a chance to look them over to see if they’ve become entangled in fishing tackle.

The Australian pelican is listed as common, thus no tally on the national or Queensland population has been done. But Dr Greg Johnston, a senior researcher at Adelaide Zoo, says he’s in no doubt their numbers are falling, and recreational fishing is a contributing factor. Opportunistic feeders, pelicans hang around fishermen looking for offcuts, and often trip over more than they bargain for. It’s a hazard of life for pelicans, but one made worse by thoughtless discarding of fishing gear. At Redcliffe, if a pelican is entangled, people will call a range of wildlife carers to look after them - including the Powers twins.

Which led to the blond brick home at Beerwah and a table covered in the hooks and lures, fishing line and sinkers that the twins have removed from pelicans’ feathers and feet. They began their volunteer rescue work five years ago and reckon they helped about 400 seabirds last year, the bulk of them pelicans. Some can be fixed on the spot, while very sick animals are taken to Steve Irwin’s Australian Wildlife Hospital at Beerwah. Patients suffering from botulism - a bacteria that occurs in stagnant waters and leads to diarrhoea, paralysis and death - get special treatment: the lice-ridden pelicans share the twins’ bedroom for up to two weeks, propped up on mattresses and cushions and fed on pulped fish, their lolling beaks held up for 45 minutes to ensure digestion.

“It’s 24/7,” say the Powers, again as one. “We get up every three hours to change the linen.” Sorry, wind back there. You change the linen? “Oh yes,” they echo. “The critical pelis, who can’t hold their heads up, we always like to make them comfortable.”It’s an interesting revelation, exhibiting a passion above and beyond the call of duty, but still not enough to change the direction of the story. Helen chimes in that her linen closet is full of formerly good sheets marked “B” for bird. Once, a fellow rescuer brought over a kilo of prawns for a barbie; the girls took them straight out to the birds. No wonder, says Helen, that their old mate, Cliffie Young, used to claim he’d come back as a pelican, so well were they cared for by the twins.

Yes, that’s Cliff Young, the long-distance shuffler who died with dementia in 2003. In fact, he spent the last years of his life at this very home, being cared for by the Powers family. It turns out these enigmatic twins met the one-time potato farmer about 13 years ago when they were living in the Wollongong area of NSW and trying their hand at modelling. Young had been enlisted to promote Senior Citizens Week and the twins were among a harem of models to be photographed with him.

The sisters tell how when the call went up to go for a meal after the festivities, Young said he’d like to go to the family restaurant Sizzler. The other models bailed out, expecting something a little more up-market. The twins, however, had been fans of the man when they were nine and he made headlines, and they were thrilled to sit down and have a yarn.

“It was like we’d known him for years - he had the same interests, he was a vegetarian, loved animals and hated treading on an ant.” From there, says Helen, it just grew, with an offer to help Cliff in the field during a fun run the next day leading to a few more runs. Before long, the Powers were managing Young and the twins had an adopted grandfather. When the family moved to Queensland six years ago after the death of Vicki, one of the twins’ five siblings, Young insisted on coming, too.

Caring for Young was difficult at times, they admit, but they would not see him go to a nursing home. It dawns that Helen and Jack Powers have done a lot of giving over the years, and that with the cost of feeding the birds alone totalling about $100 a week, it might help if the inseparable twins could turn their passion into paid work.

Helen can’t hold herself back and tells how the twins have approached the Australian Wildlife Hospital to see if a planned upgrade might include a seabird section, of which they could be a part.

The twins look bashful, not wanting to count their chickens. “We don’t know yet,” they say. “And,” continues Helen, “if all goes well, the twins will be taking a ride on the wild side.” Okay, this should be interesting. What does that mean? “Oh, the twins are going to ride around Australia to raise funds and awareness for the hospital, hopefully in October.”

It’s hard to imagine these slight, girly women getting further than Gympie on a pushbike, and the incredulity must show. “Well, they’ve done it before,” says Helen. I’m still reeling from just thinking about riding around Australia, and can’t accept this as true. Surely, their mum means they’ve done some short rides up and down coasts.

“No,” say the twins, their index fingers working in a circular manner, “around ... “ Then, with perfect timing, they deliver the killer qualifier: “... twice.” Giggles peal into the air.

This is where the pelican story took flight, and the life and times of the Powers twins and pelicans combined. It transpires that, buoyed by Grandpa Cliff - “He taught us a lot of secrets” - the twins, with their parents in back-up vehicles, set off in 1998 to ride and walk their way around the country, raising funds and awareness for the need for a rescue helicopter in the Wollongong region. They travelled 15,500km - including across the Nullarbor - from the’Gong and back, helped the community raise about $150,000, got 10,000 signatures, and the Illawarra now has a full-time chopper. All this achieved on two $157 bikes from Kmart.

Then, in 2001, when Young set off on another epic run, helping communities raise funds for the Make-A-Wish Foundation, the twins were with him. When he pulled out just three days into the run, so did much media interest, but the twins kept going on foot and bike. This time it was more of a linear crossing of the country, finishing up in Kings Park, Perth, after 14,000km.

“But that time, we went up to Cairns and we rode up that Kuranda range, 330 bends,” they chorus. “No toe-clips or nothin’, and they were heavy bikes.” Then, unusually, Bridgette breaks out on her own. “We’ll never forget that,” she says.

Returns Paula: “It was a challenge, that one.” And back in unison: “We like a challenge.” So does Gail Gipp, the wildlife hospital manager, who says she was stunned by the girls’ offer to “ride on the wild side” but thrilled to take it up.

The map for the trip has been drawn up, a seabird section is planned for the revamped hospital, and “I’d give them a job tomorrow if I could”.

Quinnie has taken up residence in the twins’ bedroom. Helen’s linen cupboard has been raided again and the blender is back in business, pulping fish. It’s a few days after our first meeting, and Paula is on the phone detailing the early evening rescue of this sickly male pelican from the Pumicestone Passage. There’s chatter in the background - Bridgette also is telling the story.

Members of the volunteer coastguard saw the distressed bird on an island in the passage and called the Storm Girls. With no boat, the twins hailed down a bloke in a Quintrex dinghy and hurtled over to save the bird. Quinnie, named after his rescue transport, was listless with botulism but they’re celebrating today - he’s managed to keep some fish down.

“He’s a lovely boy, but he’s very unwell so we’ve got him all comfy in our room,” says Paula. The girls say that once the bird is out, the lice disappear with a bit of chemical help, although it’s another matter for their little car. The old ambulance they once used has conked out, so now their Mazda Astina is in service. Trouble is, it’s too small for their pelican cage, so if you see a couple of women driving along, one with a pelican in her arms, that’ll be the Powers.

Their ultimate fantasy is to get a few hectares in the hinterland, carve a great big dam into it, and watch the birds they save grow stronger and take off into the wild again: “We don’t care what we live in, a shack will do, as long as the birds are happy.” But what of them, I ask. Are they happy, would they like to get married, have a family?

“We get a lot of questions of will we ever meet boyfriends, and we will one day, we’ve got plenty of time,” they chime. They have the same likes in a man: “No wimpy guys, a kind heart, no drinkers and, most of all, someone that understands about us, that we have to be together.” Twins, or close brothers, seem a likely option, they admit.

Never, though, have they wished they were not such a close set of twins. “No,” they say, casting quizzical glances at each other, the question clearly preposterous. So, what’s so good about it?

“Well,” they say, “you’ve got a best friend for life, and you can tell each other secrets and you know they won’t go anywhere.” Hang on a minute; can a couple of women who go everywhere together have any secrets from each other?

They’re momentarily stumped. Bridgette turns to Paula. Pelicans fluff their feathers in the breeze.

The Powers twins’ eyes meet and they beam at their mirror image, before turning back and bursting into a pair of those giggles. “No,” they say. “We don’t.”

Originally published as QWeekend: Meet the identical twinnies Paula and Bridgette Powers who’ve shocked the world