Li Cunxin is tucking into an $85 eye fillet as he talks about a childhood blighted by hunger.

“There was no food, none – people in my village would eat tree bark, rats, snakes, I was starved most of the time,” says Li, savouring mouthfuls of wagyu with red-wine jus, hand-cut chips and a crisp green salad.

“If you had a cat or dog you could not let them outside; someone would eat them, gone, people were so desperate.”

The contrast between then and now is stark, and the story of how it came to be is staggering.

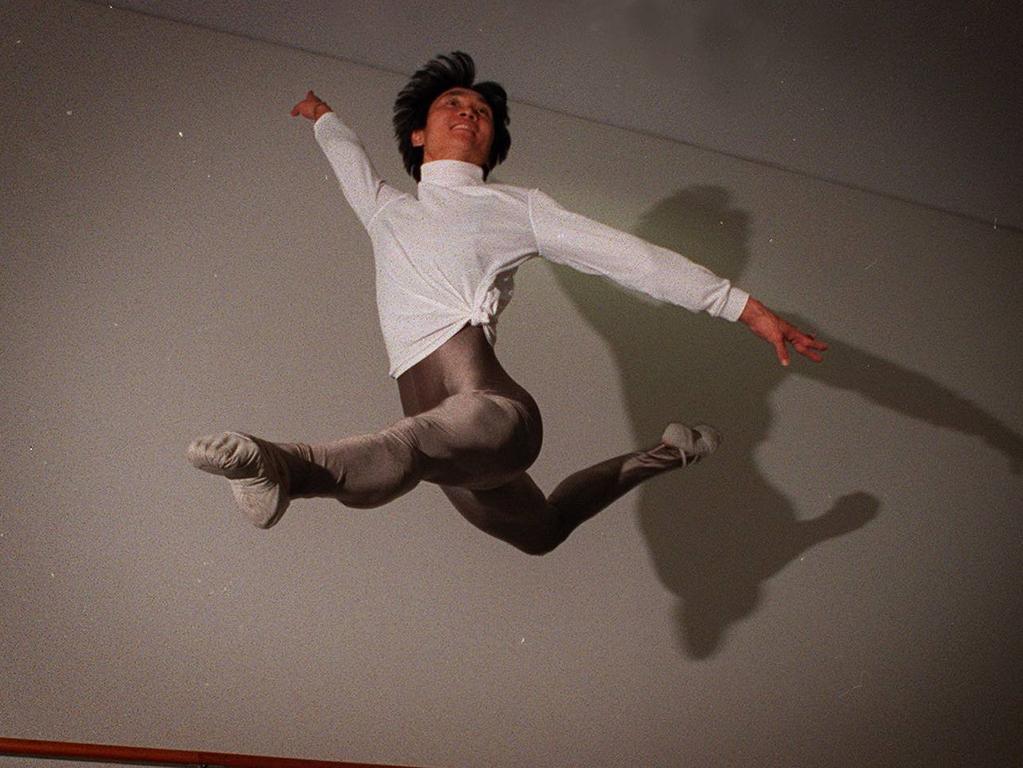

Li, born the sixth of seven sons in 1961, would escape poverty-stricken Qingdao city and eventually the brutal People’s Republic of China to become one of the world’s top ballet dancers.

He would be feted by high society, meet stars such as Frank Sinatra, and be sensationally saved by the US Reagan administration from being sent back to China against his will.

He would ultimately settle in Australia after marrying a Rockhampton-raised dancer and transform the little-known Queensland Ballet into an international success as its daring artistic director.

You might know some of this, particularly if you’ve read Li’s gripping 2003 book Mao’s Last Dancer, or watched the 2009 Hollywood film it spawned.

But hearing the man himself talk about his journey is really something.

“My whole life I wanted to save my family as ballet saved me,” says Li, 64.

“But I don’t think fame and money have changed me; if I don’t have them, I’d be the same person.”

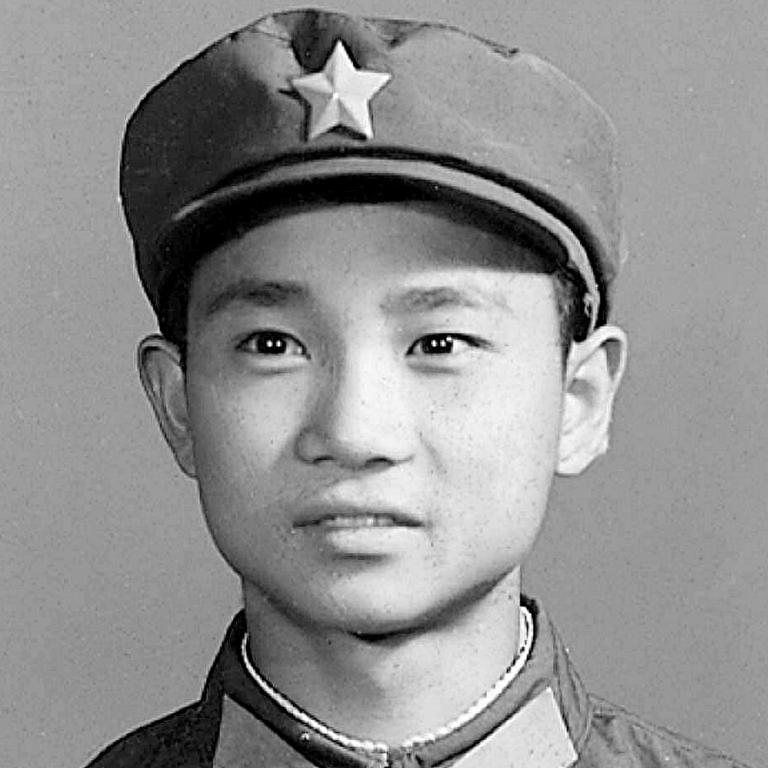

Li – actually his surname – was 11 when he was inexplicably chosen for the Beijing Dance Academy.

It was a typical day in a freezing classroom – temperatures could hit -25C – and 40 children were reciting texts from Mao’s red book when four men from the academy came in.

“We stood up and sang, We Love You Chairman Mao, as they walked around us, looking for the best bodies to serve Mao’s revolution,” Li says.

“They only chose one girl, and as they were leaving, my teacher looked my way and said, ‘What about that one?’ ”

To this day, Li has no idea why, and when he tracked down his teacher while writing his memoir, neither did she.

Li’s gruelling audition began. He was stripped and pinned against a wall as the men forced his skinny little legs higher, testing his flexibility and pain threshold as his hamstrings tore.

Li suffered in silence, as he would for many years, homesick and crying himself to sleep in the academy.

“Our bodies were broken, we worked from 5.30am to 9pm six days, and we were brainwashed,” he says.

“If the communist party told me, ‘Mao orders you to jump into a deep well and kill yourself’, I would have done it.”

Li felt enormous guilt, eating well while his family starved.

“If someone would even give me a banana, I would think, ‘how can I take this home to my mother?” but I only saw her once a year.

“I hated ballet with a passion, and I nearly failed at the end of my second year but then one amazing teacher came into my life – Teacher Xiao treated us as human beings, not bodies.”

When Li was 14, Xiao travelled to meet Li’s family.

“My poor mother had to borrow food from the neighbours to provide for Teacher Xiao but it was horrible, terrible food,” he says.

“Teacher Xiao then understood my dream and said, ‘If you become the best dancer you can be, then you could help your family.’ ”

The fire in Li’s belly had been lit – and at 18 he graduated top of his class, described by Xiao as “the last dancers of the Mao era”.

In 1979, as China was opening up after Mao Zedong’s death, a US cultural delegation was invited to Beijing and Li was selected for a summer school with the Houston Ballet.

There he met American dancer Elizabeth Mackey.

“She was my first love and I married her without thinking of the political consequences,” he admits.

The Chinese consulate held and interrogated Li for 21 hours, demanding he abandon the marriage and return to China but Li refused.

Meanwhile, at a glamorous Houston Ballet fundraiser, the absence of its star dancer was noted.

“The press got hold of the story then the FBI surrounded the consulate so I couldn’t be smuggled out of America,” he says.

“Barbara Bush (wife of vice-president George H. W. Bush) was on the board of the Houston Ballet so I was very lucky.”

While Li’s defection was successful, his marriage wasn’t.

“I had suffered so much emotionally, I was impossible to live with,” he says.

“I had nightmares and felt guilty for problems I could have created for my parents and brothers; they could have been put in jail or killed, I wouldn’t have known because China stopped all communication getting through.”

It would be six years before Li, then 25 and a principal artist, would be reunited with his parents – again with the intervention of Barbara Bush.

“My parents got permission to leave China, they couldn’t read or write, had never seen me dance, and they came to the night opening of The Nutcracker in Houston in 1986,” he says.

“It was just before the curtain went up that I was told they were in the audience – they cried throughout the performance – it was the most special evening.”

The following year Li married Queenslander Mary McKendry, who had become his dance partner in the Houston Ballet after a successful career in London.

The couple moved to Melbourne with their young family in 1995 when Li joined The Australian Ballet as a principal artist.

Retiring four years later at 38, he transitioned into stockbroking, and hit the speaking circuit on the back of his book and the movie.

Life was pretty near perfect when, in 2011, the Queensland Ballet came knocking.

Li flatly declined the offer to become its fifth artistic director but his wife had other ideas.

“Mary said, ‘Look, ballet has given us such a wonderful life, without ballet we would never have met, so it would be wonderful to give something back’.”

Li arrived in Brisbane with a vision – to build one of the best ballet companies in the world.

“It was very audacious at the time; we were so small and weak,” he recalls.

“My thinking on corporate sponsors and philanthropists was clear – if they wanted the best ballet company then they should support it.

“Somebody with my success, my fame, might say, ‘well I’m a star’, but they’re not going to get anywhere because Queenslanders would never embrace that.

“If I’d come here with a chip on my shoulder, Mary would have cut my head off.”

The tenacious Li saw Queensland as “fertile ground” for his ambition.

“Maybe it was because of Mao’s Last Dancer, people felt they knew me, but also I was very daring and when I was told there was no money, I was the one willing to find it – not many artistic directors are willing to do that.”

Li’s biggest hurdle was “engineering cultural change”.

“In my first speech to the company (in 2012) I said, ‘I’ve taken on this job not to be popular … Imagine we are at the station, we’re about to board a bullet train, and I warn you, if you are not embracing my vision you should not be coming on this train because it will be a very uncomfortable ride … and if you board but don’t pull your weight, I will push you off.’ ”

Under Li, Queensland Ballet’s annual turnover grew from $5m to $28m when he left due to ill health in 2023. The company also spent close to $200m in investments, including young artist and community health programs.

Li drove box office sellouts and the spectacular $100m+ renovation of the Thomas Dixon Centre in West End.

These days, his heart condition – brought on by stressors including “Covid turning our company upside down” – is under control and his beloved Mary is two years cancer free.

Comfortably settled in Brisbane’s inner north, they are watching their children succeed in their chosen fields.

Sophie, 34, who was born deaf, is co-founder of an online sign language dictionary. Tom, 31, is a teacher in Melbourne, and Bridie, 27, works in financial planning in London.

When we meet for lunch, Li is recently back from Switzerland where he was honoured with the Prix de Lausanne’s lifetime achievement award – and he is not done with dance yet, as inaugural chair of Queensland Ballet’s Endowment Fund.

Reflecting on his life, Li – a recipient of an Order of Australia – says he has “grown a very thick skin”.

“There are a lot of heartbreaking, shattered dream moments on the journey … but I will still be showing gratitude.”

Li says gratitude is missing in today’s youth.

“In my era we didn’t think of fame, we thought of excellence, so we really worked hard; we were satisfied because we’d become so good at what we did.

“But in the generation today, people can be famous because they are an influencer, because they become a sensation on social media and get endorsements, and you think, ‘what have they done?’ … nothing.”

“When I grew up, if somebody gives you just a little bit of food you feel so grateful, anything you get you’re grateful. So I never think, ‘I deserve that’ – never – even if I work hard for it.

“When you don’t have gratitude, you cannot appreciate the precious opportunities that come your way.”

Li has visited China many times in recent decades. His parents and older brother have passed, but his other five siblings have good businesses.

“My brothers still say I was their saviour. I think what I did with my life motivated them to do better in theirs. That’s how I view success – it’s not just for yourself; it has that inspirational effect on others.”

The steak

Stanbroke wagyu (marble score 5+) eye fillet 200g

Rating

10/10

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Newman’s arrogance led to his downfall. These two need to learn from it, fast

Considering the way the LNP behaved when last in office, this government’s future will rely heavily on avoiding any sense of entitlement. They’re off to a worrying start, writes the editor.

Theatre to cost staggering $122,000 per set after $34m blowout

Brisbane’s long-delayed fifth theatre will cost more per seat than the behemoth Olympic Stadium at Victoria Park after the project cost ballooned from $150m to $184m.