Popped eyeballs, bloody dog attacks and swallowed socks: Chaotic reality inside emergency vet

Dog bites, popped eyeballs and swallowed socks are just some of the reasons frantic pet lovers make a dash to veterinary emergency after night falls. The cost to save a beloved pet can end up in the thousands. We take you behind the scenes.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

She’s rushed into emergency in the arms of her frantic owner, bloodstained towels wrapped around her long legs, a confused look on her pretty face.

Ahead of them runs veterinary nurse Sandra Tran, calling “emergency, let us through, please”.

People in the waiting room scatter, mouths agape.

In seconds, they’re into the consulting room and the bleeding, traumatised dog is whisked through the two-way door into the main treatment area where vets and nurses get to work.

Her shaking owner, Andy Thomson, paces, sits, stands. Waits.

His afghan hound is a beautiful, lively girl, says Thomson, a bit of a princess, but tonight, sadly, she’s living up to her ironic name.

“Havoc is her name,” Thomson says, managing a wry grin. “But she wasn’t the instigator of this.”

Chaos broke out for a few long seconds just before 6pm when Thomson’s seven-year-old companion was attacked by his mum’s “bitsa bitch”.

From Boggabri in NSW, they’d been staying at Thomson’s parents’ place in Salisbury, in Brisbane’s south, for weeks without incident, careful to keep the dogs, who didn’t get on, separated. But a miscommunication about closing gates led to the two dogs being together at the same time.

“I heard it, witnessed it,” says Thomson, 39. “I pulled the other dog off, it was latched on, and that ended up ripping out a five centimetre chunk on her front right shoulder. Blood everywhere.”

Now, inside the treatment room, the blood-soaked “dodgy tourniquet” Thomson wrapped around Havoc’s shoulder is dropped to the floor as Dr Jenny Holmes and nurse Ellise Mortenson examine the wound.

They insert an IV catheter to allow drugs and fluids to flow and 20 minutes after she was rushed in, Havoc is beginning to calm down.

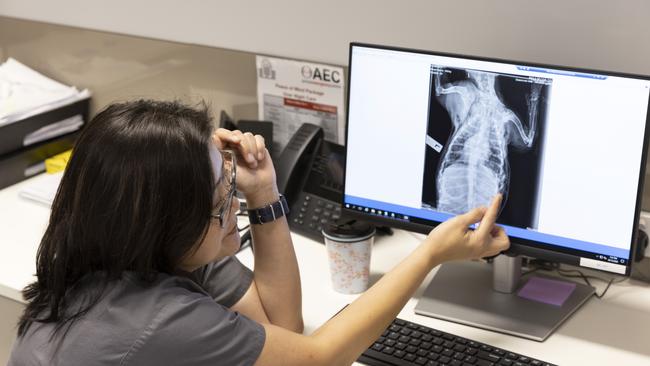

“The first thing,” says Dr Diana Chua, the veterinary director at Greencross Vets’ Animal Emergency Centre at Stones Corner, in Brisbane’s inner south, “is to provide analgesia for the pain. Get her heart settled, help with the blood pressure. It’s a very traumatic event, for the dog and the owner.”

Holmes peers at the gaping wound which has exposed the dog’s muscle. “It’s quite a big laceration,” she says.

Mortenson consoles the dog. “Good girl, sweetheart, good girl,” she says, gently stroking Havoc’s head. Havoc rests her head back down.

A bush dog, she’s recently been shaved of her long hair, but a nurse searches for any smaller nips, and shaves around them. By 6.45pm, Holmes has finished packing the wound and Havoc is bandaged up.

She’s transferred to a crate in the intensive care unit and Holmes heads out to discuss with Thomson what he wants to do next.

NIGHT FEVER

Teddy, the poodle/chihuahua, or poochi, is having a bark-off with Charlie, the maltese, in the ICU, both showing more spark than when they arrived earlier in the day.

Teddy’s owner, Mel Tesch, and her husband, Colin, jumped in the car with the sickly mutt about 2am, driving all the way from Ipswich, after he suffered a bout of diarrhoea and vomiting, some of which contained blood.

“He was very lethargic, very flat,” says Tesch, 47, “just sitting on my lap in the car. Normally he likes to get up and poke his head out the window but he wasn’t interested at all.”

His blood work shows elevated liver and pancreas levels, suggesting fatty food, but Tesch can’t think what it would be, given the 14-month-old is fed only premium dog food.

“But he is a chewer, he gets into anything and everything so maybe he got into the bin,” she says.

Chua walks into the ICU to settle the animals down and check on the other patients. “Teddy,” she says in gentle admonishment. His little face looks up at her, he sits back on his haunches, and an uneasy truce is called.

Suddenly, the doors fly open. A pug is being rushed in. There’s no need to ask why: his right eye is jutting almost out of its socket.

It’s a distressing sight; a bulbous, reddening eye pops out prominently and his breathing is ragged, more ragged than the characteristic breathing of flat-faced breeds.

Two nurses gather around as the pug is laid on the table, putting lubricant in his eye and doing their best to soothe him. It’s just after 7pm and Holmes sets off to talk with another distressed owner.

Popped eyes, known as ocular proptosis, is a risk with these breeds, says nurse manager Kirstie Hayward. “Their eyes are just not very deep in the eye socket. Stress, exertion, even a collar around their neck can do it. It doesn’t take much, unfortunately.”

How it happened is a mystery. Outside in reception, Elise Heinz, 33, and Lia Kim, 29, are waiting with their dogs, Bobo, a labradoodle, and Molly, a rottweiler cross, anxious to know how their friend the pug is doing.

His owner is too worried to talk, and does not want him named, so we’ll call him Pete.

“We know Pete really well, he’s a really friendly, sociable dog,” says Heinz.

The trio of women and their dogs were catching up as they do most days at a West End park, the women chatting while the dogs sniffed and played together.

A couple of other dogs, about the size of Molly, were there too, and Pete seemed fine as they played.

“Then we heard him whining,” says Heinz. “We turned around and just saw his eye had popped out.”

She says it didn’t protrude too badly at first but crept further out over minutes. The trio and their dogs piled into Heinz’s car and rushed Pete to emergency.

Now Bobo and Molly are sitting quietly with their owners, waiting. “It was so interesting when it happened,” says Heinz, “the way they all gathered when he was whining. They wanted to try to soothe him.”

Pete’s doing better now inside the treatment room, his breathing more settled, as Holmes prepares to operate. Nearby, a silky-soft cat, a russian blue cross called Louis, is being tended to by vet Dr Kirsty Dawson.

“His bladder is blocked,” she says of the anaesthetised cat. How dangerous is that? “Oh, this is an absolute emergency. His bladder is rock hard and that can cause issues with his kidneys. It’s also at risk of rupturing.”

The nurses clip around Louis’s prepuce and sterilise the area in readiness for Dawson to insert a urinary catheter. That will stay in for at least 24 hours, until his urine is running clear, she says.

“The blockage probably takes 12 to 24 hours but owners generally only notice it when the cat starts going to the litter box regularly and not passing any urine.”

That’s exactly what happened that morning, says Andrea Crosswell, 52, of Carindale. Louis, her daughter Julia’s much-loved cat, was in and out of his tray, scratching, but nothing else.

The seven-year-old did not appear ill and Crosswell was concerned but not alarmed and went to work. When she returned mid-afternoon, Louis had deteriorated; less active, his legs low to the ground.

She called Julia, 24, who moved out of home in 2021 to an apartment that doesn’t allow pets, and by early evening, they’re at emergency.

They’re told the smoochy, playful Louis might not make it. His fate depends on whether his organs have been damaged. They leave, with Julia distraught, and her mum keeping the phone by her side all night, on full volume.

The vets and nurses plug on, a plucky group of animal lovers who know what they need to do and get about it with little fuss.

Amid the beep-beep of monitors and the yapping of unsettled dogs, they coo to their charges as they check their progress.

Havoc is doing okay, sitting in her crate, a little dopey but settled. Louis’s catheter is in, flushing out his bladder.

And Pete is in the final stages of having his eye pushed back and the eyelids sewn shut by Holmes, with nurse Morna Geddes assisting.

“You have to pull the eyelids back because they get stuck behind the globe of the eye,” says Holmes. “So, you pull them out and then suture the eye closed until the inflammation and haematoma behind the eye is resolved.”

It’s a delicate operation but Holmes believes his eye will be saved. His eyesight is another matter.

“You get pulling on the nerve that attaches the eye to the brain as it pops forward,” says Holmes. “So that nerve will almost certainly be irreversibly torn.”

Geddes pats the anaesthetised dog. “His eye is very swollen, poor thing,” she says.

It’s 8.30pm and no one is in the waiting room. Perhaps it will be a quiet night. Fifteen minutes later, Franklin arrives with his owner, Harps Sirah, 31. The maltese/pug/dachshund cross has swallowed an ankle sock.

DON’T SAY ‘IT’S QUIET’

Before Havoc and Thomson burst into the clinic at 6.15pm that Friday, things had been relatively quiet. But there’s an unwritten rule in emergency: Never, ever, say “it’s quiet”.

“We don’t use that word in here,” says Geddes, a veterinary nurse of seven years who’s seen her share of dog bites, broken limbs, heart failure, hairballs, toxin ingestion, car accident victims, paralysis and the weird things dogs gobble up and swallow.

And pet lovers will pay to get them well. We’ll rush them to emergency in the middle of the night, take them for regular radiation therapy to fight cancer, authorise hip surgery.

We’ll sit outside in our car with our pet, just as Rico Erwin was doing earlier in the evening, until it’s time for an appointment for an immunotherapy shot aimed at desensitising grass allergies.

“That’s part of being an owner, I suppose,” says Erwin, 46, beaming down at Aaron Lee, a rare coton de tulear, with chronic itching. “You have to look after your dogs, and he’s not just a dog to me. He’s part of the family.”

The evolution of a pet’s place in our hearts is something nurse manager Hayward has watched close-up during her 23 years in the industry.

Twenty years ago, they were “disposable objects”. Especially cats. No need to spend money on an injury: knock them on the head and get another one.

“It’s been a massive change,” says Hayward. “Massive. They’re not pets anymore, they’re family members. And people treat them that way, which just didn’t happen 20 years ago. Look around, this is expensive,” she says, sweeping her arm around to take in the recently opened centre’s three surgical theatres, ICU, dental suite and magnetic imaging room.

Then there’s the monitors, the IV drips, the antibiotics, the dressings – and the commitment of vets and nurses who deal with trauma, anger and sadness every night.

The saddest part of the job, Hayward says, is knowing an animal can be fixed, that the owners want to give them treatment, but can’t afford to.

“There’s nothing worse than seeing a young, healthy dog that people just run out of money to fix,” she says. “That’s the worst.”

It’s unlikely to happen to “the very special” Aaron Lee, an 18-month-old dog who started developing grass allergies at nine months. “It would flare up, he’d be nickering his feet all the time, then it becomes infected,” says Erwin, who plans to show his fluffy, snow-white pedigree.

In a bid to rid Aaron Lee of his allergies, Erwin pays $100 a month for immunotherapy, cutting the costs slightly by ordering the medication online and bringing Aaron Lee in for the injection. He’s worth every penny, says Erwin.

Little Rosie King wouldn’t have a clue how much her father, Nathan, has just paid the vets to care for Loki, a 12-year-old maltese poodle.

All the four-year-old wants is to get back to playing chasey with him. “Loki never gets me, I always get him,” she says, giggling.

Loki has been at the Greencross day clinic a few times this week as vets dealt with his blocked anal glands that had caused bleeding.

He should be better now, says King, and with that, Rosie takes the lead and skips out with her best mate.

It’s a sweet sight, helping to dull the sadness from the knowledge of what’s going on inside the surgery. On a treatment table, being softly spoken to and stroked by Mortenson and nurse Madeline Short, is a listless senior terrier. “He’s about to go to heaven,” says Mortenson.

He has chronic heart failure. There’s nothing more that can be done. In a room dedicated to end-of-life procedures, the lights are dimmed and a calming pheromone filters through the air. A blanket is on the floor.

Then the little dog, this much-loved family pet, is carried into the room and reunited with his loving owners. For one final time.

WITCHING HOUR

Franklin is looking very sorry for himself. He’s sitting on the floor, docile and peaky, with Short’s comforting arm around his little body, a litter tray covered with a garbage bag in front of him, preparing to vomit.

Sirah is waiting in reception, still shocked by the swiftness with which the 18-month-old gobbled the sock.

“I came back from work drinks, decided to change and took my socks off, put them on my bed,” he says. “He grabbed one, I tried to grab it off him, he jumped off the bed, looked at me and just swallowed it straight.”

Sirah wonders if Franklin did it because he’s stressed or seeking attention. Sirah and partner, Nicola Jones, welcomed daughter Harvi recently and life has been busy. “I was Googling up on it and it said they eat outside of their food from stress and anxiety so that could have been it.”

Whatever the reason, the apomorphine administered within minutes of Franklin’s arrival is kicking in and at 8.53pm, a slimy ankle sock is regurgitated into the litter tray.

“There it is, good job, buddy,” says Short, giving him a consoling pat. “No more playing with socks, dude.”

After a few more bilious deposits, Franklin receives anti-nausea medication and he’s back in Sirah’s arms within half an hour of coming through the door.

Swallowed socks are a common issue in emergency, says Hayward. “And tampons. Condoms,” she says. “Oh yes, a delight! They’re very frequent. And socks and jocks, they just smell good. Dogs love them.”

It appears to be witching hour for swallowing dangerous things.

Within minutes of Franklin’s discharge, Short is back with the litter tray, waiting for a chihuahua to vomit up grapes, which are toxic to some dogs.

Next minute, she’s asking Hayward to watch over the chihuahua. “Just until we make these other two vomit,” Short says. Prancing about the room are a couple of terriers: they’ve eaten about 120 grams of dark chocolate brittle.

As the flurry of litter trays and vomit continues, Holmes and Geddes slip into the ICU and gently ease Havoc out of her crate.

They take her to a quiet area away from the hubbub. She looks calm. She’s injected with an anaesthetic and soon, those long legs start to wobble. They hold her, wait for her to falter, and guide the sleepy girl to the floor.

It’s 9.50pm. Havoc is lifted onto a table and a tube inserted down her windpipe. “We give them an IV anaesthetic first, it lasts about 20 minutes so we can get a tube in, and then they go on a gas anaesthetic,” says Geddes.

Now Holmes can get a good look at the wound. “It’s about five or six centimetres in length, about three in width,” she says. “It’s gone through the skin and subcut(aneous) tissues, there’s a puncture wound in the muscle there, and down there.”

Holmes feels below the gaping wound. “She’s got a bit of gas stuck under the skin.” Geddes asks if it will require a drain.

“Probably, we’ll see how much dead space there is. The pocket forms because of the shear forces with dog bite wounds; they grab and they shake so the skin is torn off the underlying tissues. You’ve got two layers, skin and body wall, that essentially aren’t attached anymore so that’s a potential space for fluid to fill up in between. Big pockets of fluid or gas are prone to becoming infected and forming an abscess.”

Holmes checks manually for any breaks because x-rays aren’t going to be taken “to trim the bill for the client”. Thomson has been quoted $3000 to have Havoc patched up.

Holmes finds no breaks and begins to flush the wound with saline as Geddes monitors Havoc’s gum colour and medical equipment to ensure she’s travelling well. Holmes declares herself a “pedantic flusher”, making sure every pocket, every layer, is thoroughly doused.

Then there’s a spurt of blood. “We’ve got a bleeder,” she says.

A clot that formed, either through bandaging or time, has been disturbed by the cleaning. Holmes puts a clamp on the minor artery. She’ll suture it later.

“There’s an awful lot of redundancy in blood supply so there’s plenty of other blood vessels that blood can be diverted around to. Had she lacerated a major artery, a major tree to all the others, then you’re in trouble.”

After almost 30 minutes of flushing the wound and Geddes scrubbing the skin surrounding it, it’s time to move Havoc to the surgical theatre. They transfer her carefully to the bed and Geddes puts a blanket over Havoc to guard against hypothermia while Holmes puts on her surgical scrubs.

About 10.45pm, Geddes strokes Havoc’s long, soft ears and Holmes begins to stitch her up.

ROAD TO RECOVERY

Havoc is back to her old self, bounding about the banks of the Namoi River in Boggabri, a feisty princess who bears a scar.

After her discharge the next day, Thomson tended to her with salt water baths and hugs and he says, “she’s doing okay, doing great, really”.

He’s grateful Havoc was well cared for but says the bill of $3100 was a shock. He wonders, too, how veterinary staff deal with what they see daily.

“When I picked her up, I saw people in a lot of grief,” he says. Some couldn’t afford the treatment their pet required. “They (the staff) deal with a lot of trauma. How does the staff cope with this trauma?”

It’s not easy, says Chua. “All of us feel very, very strongly about certain cases, we’re all very empathetic, we have to be to be in this profession,” she says.

“Sometimes you see staff tear up a little bit and cry. And you have to give them that time, that space. Because you can’t just shut it down, close this chapter and move onto the next one, it doesn’t work that way.”

They cope with humour, talking through the case, taking time out, lollies, reading kind letters from clients – and celebrating those pets who walk out to sniff another day.

Pete, the pug, was released the next morning and after some time recovering and having his stitches out, he’ll be back to enjoying play dates with Bobo and Molly.

When Teddy, the cutie poochi with pancreatitis got back home, his older pal, Stella, a maltese cross, was waiting at the gate. “She missed him,” says Tesch.

Louis, the russian blue cross, is doing well, back to jumping out from behind the couch to frighten his best mate, Winnie, the miniature poodle.

Their owners are pretty thrilled to have them home too. “Oh absolutely, absolutely, he’s my bub,” says Tesch of Teddy. “He’ll put his head on the pillow and just watch me while I’m sleeping. He’s just really sweet.”

It cost Tesch $2500 to get Teddy back to health (insurance paid all but $570), and it was a similar bill for Crosswell. They’re fine with that.

“I felt it was reasonable; I can’t speak highly enough of them,” says Crosswell. “He had most of his interventions at night, and that costs more, of course. Small children and animals,” she says philosophically, “will always need to go to accident and emergency at night.”

And ready for their arrival will be the vets and nurses of emergency veterinary care – soothing, diagnosing, stitching and putting a comforting arm over impulsive little dogs as they vomit up an ankle sock.

More Coverage

Originally published as Popped eyeballs, bloody dog attacks and swallowed socks: Chaotic reality inside emergency vet