Matthew Benns: Sydney pioneer John Bradfield would want us to be bold

If a wormhole gave Sydney Harbour Bridge designer John Bradfield a chance to see the city sprawling outwards from his famous creation, he would likely approve, writes Matthew Benns.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

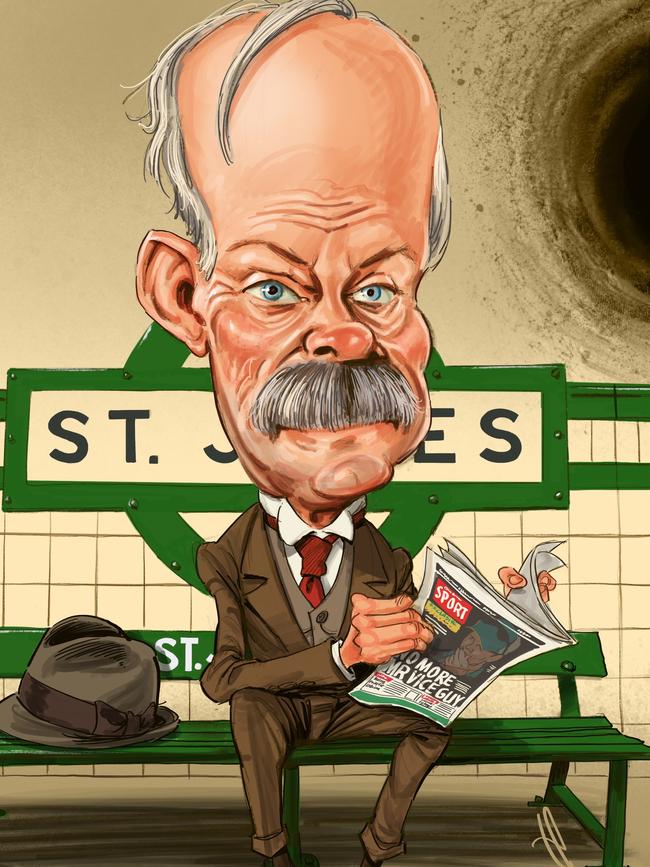

The man who emerged blinking into the light from a disused tunnel at St James Station in the middle of Sydney appeared confused.

Dressed in a heavy three-piece suit and wearing a Homburg hat it was fortunate that the first person he bumped into was a representative of The Daily Telegraph.

“I feel slightly disoriented and I cannot be late for the opening of the Harbour Bridge,” he said.

Ah, right. Off with the pixies then.

“No, I’m the designer. I’m John Bradfield, this is my big day.”

It is fair to say that Mr Bradfield was taken aback to be told it was 2021 not 1932, and he was even less impressed to hear that Francis de Groot was about to jump in front of premier Jack Lang and cut the ribbon with his ceremonial sword.

“Einstein indicated time travel was possible,” mused Bradfield. “Perhaps a wormhole in time has opened up. Has there been any tunnelling around the harbour?”

Funnily enough, the tracks have just been laid on the Sydney Metro, the first rail crossing under the harbour.

“Trains under the harbour, whatever next? Cars?” said Bradfield, his bushy moustache bristling at the news they had been zooming under the harbour for years. “Anyway, I must be getting back to 1932.”

But who could pass up the chance to get the verdict on modern Sydney from the architect of its greatest triumph, the visionary eight-lane Sydney Harbour Bridge. Originally taking 11,000 vehicles a day and now handling 160,000 with ease.

“I don’t understand why St James Station is so quiet,” he said as we walked up the stairs. “I designed this as a major interchange. This was meant for the lines out to Watsons Bay, Botany and Maroubra. The lines to the Northern Beaches are meant to run from Wynyard.”

Oh dear, bit of a disappointment on that one. Hard to explain why the train to Bondi Beach stops at Bondi Junction for a start.

“Don’t tell me people are still struggling with getting across The Spit,” he sighed, as we walked towards George Street. “Still got the trams I see.”

Well, actually, we ripped them up in 1961 and then put them back.

“Some things don’t change though,” said Bradfield. “I would bet the premier is still more likely to be a good Catholic father of six than the daughter of Armenian immigrants.”

Some things can be just too hard to explain.

“What is that?” said Bradfield, pointing to the Opera House as we reached Circular Quay. “I love it. And there’s my bridge. Beautiful.”

Just as exciting for the great engineer was the Cahill Expressway, which completed his vision for the City Circle train loop.

As he marvelled at the skyscrapers an Uber arrived to show him what else we had done with his city.

“Gosh, an electric car,” he said, getting into the Tesla. “What a clever steam engine. Charge it with coal fired electricity and store it for when you need it. Ingenious. Keeps the soot out of the city.”

We tootled out towards Barangaroo and Darling Harbour.

“This should be the western gateway to the city,” said Bradfield. “It is the only natural place for the city to expand. What’s that?”

It is fair to say that the engineering genius was delighted with the smartphone app for The Daily Telegraph.

“Marvellous, a newspaper in your pocket. Thank goodness it’s The Telegraph and not that other mob, all they ever want is more penny farthings on ridiculous cycleways.”

Once his concerns about the range of the electric vehicle were assuaged, Bradfield was impressed with the interconnectivity of the city’s motorway network – he especially loved the NorthConnex tunnel that takes traffic to the M1 as a high-speed alternative to the Pacific Highway and away from his home in Gordon.

“A three cities plan, a Harbour City, a central river city and a western city,” said Bradfield as we sped out towards the new Western Sydney Airport at Badgerys Creek.

“It works as long as you get the infrastructure in place. There would be no point doing it and then not building a fast rail connection between the existing airport and the new one for instance,” he said. “Or worse, stopping any rail connection at St Marys, leaving you hours from the city.”

We got out and stood in a field. Bradfield took off his hat and scratched his head.

“Why have you brought me here?”

It was of course the site of Australia’s newest city, a modern technological metropolis to be named Bradfield in his honour.

“Oh I say,” he said, dabbing his eye with a hastily pulled out handkerchief. “That’s really rather nice. I do think Edith will be quite pleased.”

By now the great man was getting rather anxious about the continued availability of his wormhole back to 1932 and the range of the Tesla to get him back to St James Station. He nodded off on the way back to the city – apparently time travel can be tiring.

“Thank you for the tour,” he said once we were back at the entrance to the old abandoned tunnel.

“I can see there have been a few missed opportunities but the city is in good shape overall. Remember, Think Big and be bold.”