Anzac Day 2022 not too different from mid-WWII commemoration

While we’ve been transfixed with the war in Ukraine unfolding on TV during 2022, the Australians of 1942 had been watching newsreel footage of much the same thing, Warren Brown writes.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Imagine if you could somehow transport yourself back through time to appear in Sydney at this precise moment eighty years ago – Anzac Day 1942.

If you were to witness the dawn over Sydney Harbour on that Saturday of April 25 1942, at first glance the city would appear as something of a strange mix of the familiar and unfamiliar – the giant span of the ten year-old Harbour Bridge hosting an unlikely smattering of cars and trams and steam trains – this engineering marvel now accompanied by the latest symbol of Sydney’s modernity – the city’s tallest structure – the recently completed AWA Tower in York Street.

Where you might expect to see the Opera House you’d find instead a tram depot – home to many of the city’s innumerable whining, ponderous green and yellow trams – and at nearby Circular Quay you might perhaps glimpse the four-year old steam-powered ferry South Steyne – the pride of the maritime-transport fleet.

Yet you’ll also feel the tensions of a city under wartime conditions – the startling prevalence of soldiers, sailors and airmen wandering Sydney’s streets – slouch hats and sailors’ caps and the dark blue uniforms of the RAAF – shop windows taped up in readiness for an air raid – the banks in Martin Place heavily fortified by sandbags.

On face value the city and its people would certainly appear different to today – men sporting pork-pie hats and three-piece suits and women fully attired with handbags and dresses – but these visual differences aside, the parallels between Sydneysiders then and now are particularly sobering.

In the same way we’ve been transfixed watching the war in Ukraine unfold on TV during 2022, the Australians of 1942 had been watching newsreel footage of much the same thing – lumbering tanks smashing their way through the smouldering remains of once great cities, the plight of millions of refugees flooding across borders, innocent civilians barbarously killed, supposedly invincible warships now lay at the bottom of the sea after only minutes of attack – Europe, the epicentre of world culture brutally razed by a policy of cruelty and barbarism on an unprecedented and unparalleled scale.

Certainly, Australia had been heavily involved in this European war from the outset – since the declaration against Nazi Germany in 1939 – where thousands of Australian servicemen and women had volunteered to take part in the fighting on land, sea and air in Europe and North Africa.

By the Anzac Day of 1942 Australia had been at war for over two and a half years yet the Dawn Service on this day eighty years ago would be commemorated squarely during the nation’s darkest hour.

The grip of war had been been slowly tightening around Australia and Australians – tragedy was edging closer to home by the day.

Five months earlier, the pride of the Royal Australian Navy – and our city’s namesake – HMAS Sydney was lost with all 645 sailors the result of a particularly vicious battle with the German Raider Kormoran off the West Australian coast.

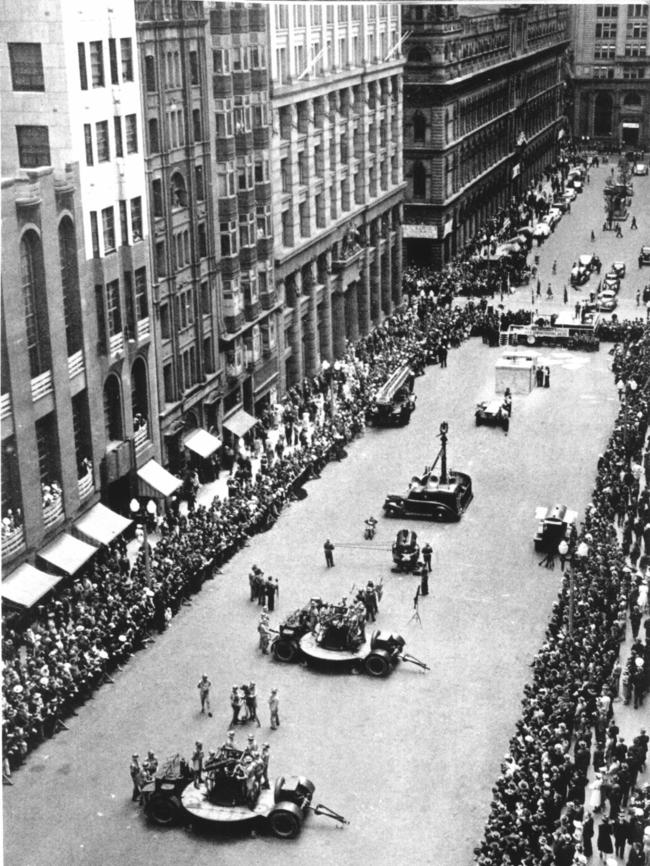

In a particularly cruel twist the people of Sydney had only recently cheered and feted the entire ship’s complement, marching through the city’s streets as heroes having returned from operations in the Mediterranean.

But now these hundreds of young Australian sailors had suddenly disappeared.

For Australians the war on the other side of the world was no longer confined to the skies of Europe, the numerous seas within the Mediterranean and the deserts of the Middle East – the swift and unexpected Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in the previous December and the subsequent calamitous fall of Singapore to Australia’s north only two months before, stoked a growing fear Australia would be next.

And in the February of 1942 that fear would be realised – the war had reached our shores.

Although the Government did its utmost in trying to censor the news, Darwin had become the next target for the rolling Japanese onslaught south through the Pacific and despite the efforts in trying not to alarm the populace, word of the attack – which had killed 235 people – had begun to filter through.

In the minds of many, what was dismissed as an unlikely chance of an enemy attack on Sydney was now shaping up as a very real probability – perhaps even the likelihood of invasion – and much in the same way during our recent pandemic, Sydney went into lockdown.

Despite some 20,000 attending the Sydney Dawn Service of 1939 – for the first time, national wartime security restrictions dictated the Anzac Service of 1942 to be held indoors.

This Anzac Day Martin Place would lie empty – an eerie silence pervading Sydney’s cavernous streets – no crowd at the cenotaph, no military brass band nor would there be the familiar sound of marching columns of the WWI veterans, men now in their mid-forties who knew full well the cruelty of war.

Even the inaugural Dawn Service to be held that year at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra prohibited large gatherings in case of Japanese attack with neither a march nor a memorial service.

But despite these restrictions and the pall of war hanging across the nation, the Australian spirit in the importance of commemorating our war dead still proved indomitable and in the pre-dawn darkness of 25 April 1942, a handful of pilgrims made their way to Martin Place to honour the fallen.

Yet the Anzac Day of 1942 would transpire to be the eye within a much bigger storm – a moment of calm in the centre of a cyclone that was about to send Sydney into a blind panic.

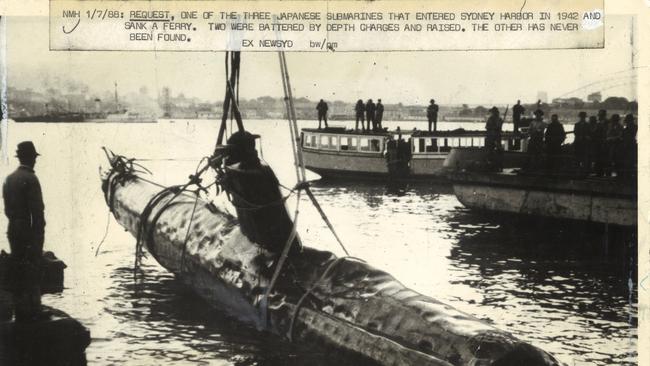

A month later in late May, three Japanese midget submarines silently entered Sydney Harbour with the intention of laying waste to Australian and American warships moored there, ultimately sinking the converted ferry HMAS Kuttabul killing 21 sailors – and later the submarine I-21 unsuccessfully attempted to shell the Harbour Bridge.

Despite the dubious outcomes of these operations for the Japanese, these actions shocked Sydney’s residents to the core – the unthinkable had happened and the enemy was now here.

But instead of destroying the city’s morale, these actions soon galvanised Sydney – the people steeled in preparation for further enemy attacks and filled with resolve.

Those of the class of 1942 were an inspirational generation which knew full-well the horrors of a previous World War, the despair of a Great Depression and what it was like when faced with a cruel enemy at their doorstep.

The people of Australia during that time – whether at home or on the battlefield – embodied the same determination and resilience we come to associate with Anzac – it’s unlikely we’ll see a generation like theirs again.