It is the oldest operating jail in NSW, housing sex offenders, murderers and disgraced celebrities. Among the inmates at Cooma is Jarryd Hayne, the former sporting uber-start. Sydney Weekend went inside the jail in November 2021 and discovered Hayne’s harsh life behind bars.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Jarryd Hayne served nine months in Cooma jail after he was found guilty of sexually assaulting a woman at her Newcastle home on NRL grand final night in 2018. He was released in February 2022 after having his conviction quashed by the Court of Appeal. He will now face a third trial.

For almost 17 hours a day, former footballer Jarryd Hayne sits in a dark, cramped cell, which is just over an arm span wide.

The only source of natural light is from a window slit high above, which is often covered with sheets or clothes to shield against the bitter cold – or searing heat.

An open toilet is positioned next to the double metal bunk, which sits across from a desk and shelves.

As the double bunk suggests, most of the inmates here at Cooma Correctional Centre must share with one other. With no shower, the cell is deemed “below standard” by the on-duty prison officer, who says those in other jails all feature this basic facility.

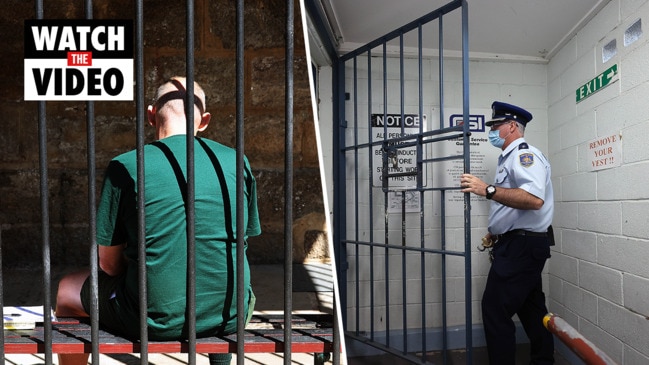

Despite being almost November, it is a cold 4C when Corrective Services NSW officers from the prison invite Sydney Weekend in to experience first-hand what it is like behind the barbed wire and sandstone walls of the former lunatic asylum that now holds the title of being state’s oldest working jail.

It is here Hayne was sent in May after three weeks at Parklea, a privately run jail in Sydney’s western suburbs which houses some of the members of outlaw motorcycle gangs.

Like other high-profile inmates, Parklea authorities placed the convicted rapist away from the other inmates, in a medical clinic.

He was still recognised by other prisoners after walking out into an attached yard, prompting them to throw their apples at him.

While none of the flying fruit hit Hayne – a steel fence stood between them – it reinforced the need for the footballer to be placed in a jail such as Cooma, where he would be with other protected inmates.

His prison records earmark him a “Public Interest Inmate”, attracting wide public attention with the classification in May.

But once he was inside the walls at Cooma, he was just another inmate doing hard time.

He is Prisoner 661736.

HOW DID HAYNE END UP HERE?

In prison terms, Hayne has scored a double whammy. He is both a convicted sex offender and a celebrity.

And neither guarantees you any favours behind bars. Not even his popularity on the footy field counts for much in Cooma.

Hayne maintained throughout his trial that he was innocent and that he had consensual sexual relations with a fan he met on social media.

The first time he faced court, there was a hung jury, but the second trial ended with a guilty verdict.

A jury of seven men and five women took three days of deliberations to find Hayne guilty of sexually assaulting the woman — who cannot be named — in the bedroom of her Fletcher home, which she shared with her mother, on NRL grand final night in 2018.

He was sentenced to five years and nine months in prison, but is eligible for parole after three years and eight months.

Hayne continues to deny that he assaulted the woman after stopping off at her house on his way back to Sydney following a two-day buck’s party weekend in Newcastle and is appealing his conviction.

During sentence hearing proceedings in May, in repeated denials, Hayne told the court: “I didn’t do it.”

Hayne’s barrister, David Baran, has said he would be agitating for a defence of consent.

The court has previously heard that the woman refused to consent to sex after she discovered that he had a taxi waiting outside to take him to a corporate event in Sydney.

The jury accepted the woman’s version of events that she said “no” and “no Jarryd” before he performed oral and digital sex on the woman without her consent.

Judge Helen Syme said Hayne only stopped when he noticed blood on his hands after his actions caused two lacerations to her genitalia.

After Hayne left, the woman texted him, saying: “I know I’ve talked about sex and stuff so much but I didn’t want to do that after knowing the taxi was waiting for you.”

Hayne replied: “Go doctor.”

COOMA’S PRIMITIVE HISTORY

Built in the 1870s, Cooma prison has served as police cells, army storage space and a lunatic asylum before it was remodelled and reopened in the late 1950s as a jail.

The prison was shut down in 1998 only to reopen in 2001 to cope with the state’s soaring prison population.

It is now the oldest – and with 163 inmates, the smallest – operating prison in the state.

Housing medium and minimum security inmates, the men-only jail is often dubbed a “white collar prison”. It’s where they send corporate criminals, corrupt politicians and celebrity drug dealers to serve out their sentences.

But unlike the celebrity prisons in the US which resemble high school dorms, Cooma jail is about as luxe as a medieval fortress, with sandstone walls, dark, narrow corridors and heavy, barred doors with oversized locks and keys.

The officers call Cooma “The Wing”.

Other prisons have multiple zones, but this one is so small, it has just one area for all to mix together.

“It also gets really cold,” says Cooma Correctional Centre Senior Assistant Superintendent Craig Jones, who arrived here three months ago from the Mid-North Coast Correctional Centre in Kempsey.

“We’ve even had snow.”

Despite the harsh conditions, and possibly in a show of bravado, Jones says the inmates do not mind standing outside in the elements for the daily muster.

“Snow, sleet … they’ll still stand outside,” he says.

But while each prisoner is given two blankets, most ask for a third or buy their own doona, Jones says.

There is no grass and the only recreational space is a small, concrete quadrangle.

Despite a Broncos towel hanging in the doorway of one of the cells, the only football played here is of the round-ball variety.

Every weekend, the prisoners run their own matches. In between games, there is an outdoor gym or a basketball hoop for inmates to get their blood pumping.

Today, a group of shirtless inmates are walking laps, which they will do until the siren sounds to be locked back in, and which some will continue to do in their cells.

There is not a lot else to do.

A prison source says Hayne is a regular at the gym.

“They all like to keep fit – even if just walking laps, which is a prison thing,” the source says.

“There is not a lot of room to keep fit.”

Everywhere there are signs, reminding us that we are in a prison: “Do not walk on the mesh or you will be charged.”

HIGH PROFILE PRISON INMATES

Hayne is among a long list of high-profile prisoners that have ended up in Cooma.

Other A-list offenders to have been incarcerated here include former government minister Eddie Obeid, crooked cop Roger Rogerson, celebrity drug dealer Richard Buttrose, former Auburn deputy mayor and property developer Salim Mehajer, Sydney banker and husband of influencer and PR maven Roxy Jacenko Oliver Curtis, and fake collar bomber Paul Douglas Peter.

But celebrities are not the only inmates needing protection.

Also at Cooma are murderers, child sex offenders and anyone else that fears for

their safety in a mainstream jail. They are in the majority.

A prison source this week said among the crowd of dishevelled inmates covered in tattoos and sporting greasy, unkempt long hair, Hayne stands out.

The former professional athlete’s hulking frame is difficult to miss and the confidence that comes with fame still evident in the way he walks about the prison, even though he pretty much keeps to himself most days.

Once here, many are unable to ever mix in a general jail population again.

“We get one truck a week at Cooma,” says Jones.

“It comes from Goulburn, where a lot are transferred. We have a lot of inmates come from Sydney. The truck arrives every Wednesday between 11am and 1pm. We can get up to 18 new inmates, although with Covid, it’s been a lot less.

“Protection inmates are at the bottom of the food chain.

“They are protected prisoners at other jails because they owe money, are high-profile or fear for their safety. They come here and lose that protection and be like every other inmate in here.”

Another long-serving officer, speaking on the condition of anonymity, puts it even more bluntly: “A protection inmate has the same status as a paedophile – weak”.

“If an inmate is known to have been in protection, he can never shake that status off.”

While inmates can ask to be placed in protection, others – like Hayne and other high-profile celebrities – have this decision made for them by prison authorities wanting to avoid disturbances.

There have been reports Hayne even fought against being placed in protection. After being pelted with apples in Parklea, he reportedly didn’t want any special treatment.

‘SOME WANNA BE GANGSTAS’

Under strict privacy laws governing NSW prisons, we are not allowed to identify the inmates we see on our tour.

But it’s hard not to do a double-take when a familiar face emerges – even though stripped away now dressed in prison greens – from the sea of mullet ponytails, neck and face tattoos.

While some of the prisoners appear to enjoy the disruption of their routine that comes with a media visit, others hide their faces with their hands or bury their heads into their jumpers as we pass by.

Some of the more recognisable inmates that we see do not make any effort to hide.

While the inmates are safer here than they would be at other prisons, just because most of the inmates were sent here for their own protection, it does not mean the jail is free from “prison politics”.

One inmate sewing prison overalls in the textiles room says he enjoys participating in the work program as it helps passed the time while also ensuring there was no trouble.

“It makes it feel less like prison,” he says.

“There’s still a lot of prison politics out there. Some want to be gangstas.

“It’s my first time here and I just want to do my time and go back to my family. I treat it like a normal job – get up, come here, work, go home. I’d work weekends if I could.”

Sewing greens, underpants and high-vis vests is the first job all the inmates sent to Cooma undertake, earning them between $26 and $50 per week to spend on the buy-up.

In a week, the inmates can produce around 2400 sets of underwear.

The overalls are the hardest of the items to make, requiring four inmates to complete.

Others are “snippers”, removing thread from the each of the items before they are packed away to be sent to other prisons.

Many of the inmates today look like they have walked off a construction site.

Textiles Unit senior overseer Anna Weglarz agrees that for most, it is their first time behind a sewing machine.

A few have mastered the skill from a previous incarceration.

The inmate we spoke with – who was a construction worker from Sydney’s west – said he was now considering taking up a job in the textiles sector once released.

Not everyone is as enthusiastic.

“Some really love it and just want to work all the time,” Weglarz says.

“Some are a bit untidy. Every item is inspected properly. Untidy sewing is not allowed.”

Hayne started in the sewing room. But he was among those who wanted out, with a prison officer at the time describing him to The Saturday Telegraph as “no seamstress”.

Instead, the footballer is undertaking a traineeship in the laundry business.

A MUNDANE EXISTENCE

From the money they earn, the inmates can supplement the daily prison meals with items from a grocery list, which offers everything from quinoa to a White Wings cake-in-a-cup.

On the menu today are roast beef sandwiches and spring rolls for lunch which are served up with a banana.

Dinner will be roast chicken with chat potatoes in an airline-style container.

The officers will be popular today as it is meat, not fish.

“No one wants the seafood,” one of the officers says. “They call it Maroubra food.”

Breakfast is the same each day – a cereal pack with instant coffee or tea.

If inmates are not working, they are attending courses.

Jones says Cooma is a HIPU jail – a “high intensity programs unit” prison.

Among the “very intensive” programs offered to inmates include those tackling domestic violence and drug and alcohol abuse.

“There’s a lot of money that is being spent on programs, especially domestic violence,” Jones says. “It’s to stop recidivism, which is one of the Premier’s priorities.”

Other inmates are pursuing university degrees.

While the activities may keep inmates from dwelling on their circumstances, the harsh reality of where they are comes at 3.30pm, when they are locked in their cells until 8am the following morning, or just under 17 hours later.

TVs must be rented or bought with work money – and there is no Foxtel.

While at Parklea, an officer overheard Hayne asking if he had access to Foxtel on the prison intercom.

Not everyone copes with the confinement – there is a self-harm facility and two segregation cells should an inmate need more intensive monitoring.

The distance from Sydney also makes it harder for family and friends to visit frequently – the wife of corrupt politician Ian Macdonald famously complained to former premier Gladys Berejiklian about the inconvenience of her husband being jailed at Cooma.

The tyranny of distance is not the only thing that’s been keeping Hayne from seeing his family and friends. Covid has put a temporary stop on prison visits, with inmates able to talk to people only via video link.

Should Hayne be forced to complete his sentence here, he could be reclassified

as a minimum security inmate and join

the inmates across the road working on a prison farm.

Some of the minimum security prisoners also take part in work release programs, including running tours of the Corrective Services NSW Museum next door.

NFL INCIDENT IN THE US

Hayne’s gloss as a sporting hero began to dim during his ill-fated trip to the United States to try his hand at the NFL.

There were many non-believers. But one of them wasn’t Hayne himself.

With iron-strong confidence about his skills and fresh from winning his second Dally M Medal, Hayne announced in late 2014 he was leaving the NRL to move to the US.

While he struggled to adapt to a game

that was fundamentally different, it was

an off-field incident that would eventually spark his sudden departure from the San Francisco 49ers.

Hayne’s NFL journey was a heady mix of early promise and ultimate disappointment.

Just six months after announcing he had been signed up with a futures contract for the west coast team, his debut in the first match of the 2015 season saw him drop his first three attempts at a punt reception.

Demoted to the practice squad in November, Hayne was given another shot at the 53-man roster in December.

But this on-field opportunity came just days after a chaotic night of team drinking that would ultimately end his US career and see a young woman accuse him of raping her while she was blackout drunk.

The woman joined Hayne and some teammates for post-match drinks at a dive bar not far from their bachelor pad. Friends of the woman, who was identified only as JV, later told police they had never seen the churchgoing Christian in her mid-20s “so intoxicated” before she joined Hayne in an Uber back to his place.

JV, who later said she was a virgin who had been saving herself for marriage, told police her last memories of the night “were falling face down in the bed, seeing a light from the hallway, and the continued sharp vaginal pain”.

The woman said she was too frightened to come forward but suffered vaginal pain for months afterwards, and in April 2016 was examined in a hospital emergency department, where concerned doctors called police to her bedside.

In early May, JV finally reported the assault to San Jose police and on May 15, Hayne sensationally announced he was leaving the 49ers to pursue a spot in Fiji’s Olympic Rugby Sevens side.

US police ultimately said they didn’t have enough evidence to charge Hayne with rape, which he denied. But he settled JV’s civil claim for close to $100,000 in August 2019, almost a year after the Hunter Valley rape that ended up sending him to an Australian prison.

HAYNE’S APPEAL

How long Hayne will have to spend in Cooma prison hangs on the outcome of his appeal against the rape conviction.

In what shapes as potentially the final roll of the dice for the former NRL star, Hayne, 33, will appear before the Court of Criminal Appeal of November 29 to argue to have his conviction quashed.

Hayne will appear via videolink from prison, 206 days since he was placed in handcuffs and led away by Corrective Services staff inside the Newcastle District Court.

On top of that, he is facing a second civil action, lodged by his victim in the Australian rape case. He is being sued in the NSW Supreme Court for aggravated damages.

The victim, who has never spoken outside court, is still traumatised and friends say she is dreading the appeal process, because it will be the third time she has had to relive the ordeal in public.

Her circle of close friends and the police who investigated the case are fiercely protective of the now 26-year-old and her mum. They are worried anything can happen in an appeal, especially given the case resulted in a hung jury the first time around.

The outcome of both legal actions are uncertain but Hayne’s legal team is not taking any risks of jeopardising the chances of success.

A key part of the strategy is for him to lay low – a message also passed on to his family and friends.

Hayne rejected offers for an interview in prison and his legal team will not comment on the appeal. They don’t want to take any chances and are confident the facts will speak for themselves.

None of Hayne’s former teammates or friends will talk about the case either, or Hayne’s state of mind. They keep a protective bubble around Hayne, much the same way they did before he went to prison.

They have also formed a support team for his wife, Amellia Bonnici, and their two children, who have stayed in Newcastle.

Revealed: Who Minns will promote after Haylen scandal

As Premier Chris Minns prepares to reshuffle his cabinet, a new face is set to be promoted in his frontbench refresh.

Secret document that warned Minns Gov about Moore Park golf plan

A secret document obtained by The Daily Telegraph under freedom of information laws show why Planning Minister Paul Scully is facing more pressure over Moore Park Golf Course.