IT’S my gloss rather than anything scientific, but there are basically three types of bikies in the underworld hierarchy. Every gang has them: there are dilettantes with day jobs who make up the numbers; there are hard cases who take orders and usually have a drug problem; and there are chapter bosses who collect money and generally do a lot of complaining.

Between these three levels are men of high value: drug cooks, ex-army officers, former cops, guys with government jobs who are useful to keep around.

(A long-standing rumour about the bikies is their ability to access official databases for names and addresses of gang enemies, or people in debt, and sometimes police.)

Interestingly, most gangs tend to be decentralised with chapters operating as their own entities, each riven by the same political infighting and popularity contests, petty jealousies, bloodlettings, scandal and sensational rumour-mongering, the kind that can get a person killed if they’re not careful.

A quick primer on each gang below:

First, the Rebels, until recently a dominating force, their membership peaking at 2000 members with about 500 across New South Wales.

They suffered under Raptor, never quite recovering from 1) the exile of Alex Vella and 2) the death of Simon Rasic, their National Sergeant-at-Arms, who died of natural causes in 2014.

Members thinking of getting out of the club took advantage of the instability and jumped while no one was looking. “There were a lot of grievances,” says Warren Gray, NSW Manager of the Australian Crime and Intelligence Commission.

Gray says Vella ran the club like a pyramid scheme, which annoyed people, and some felt the “money was going up the chain for very little in return”.

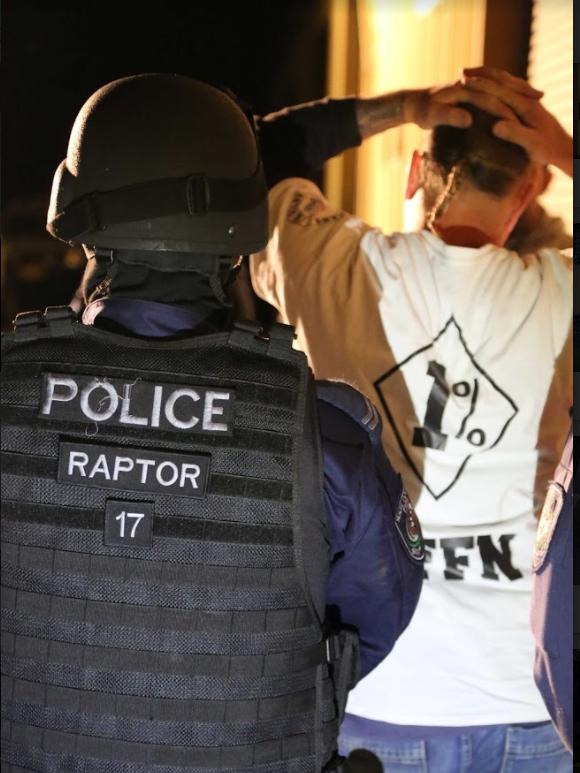

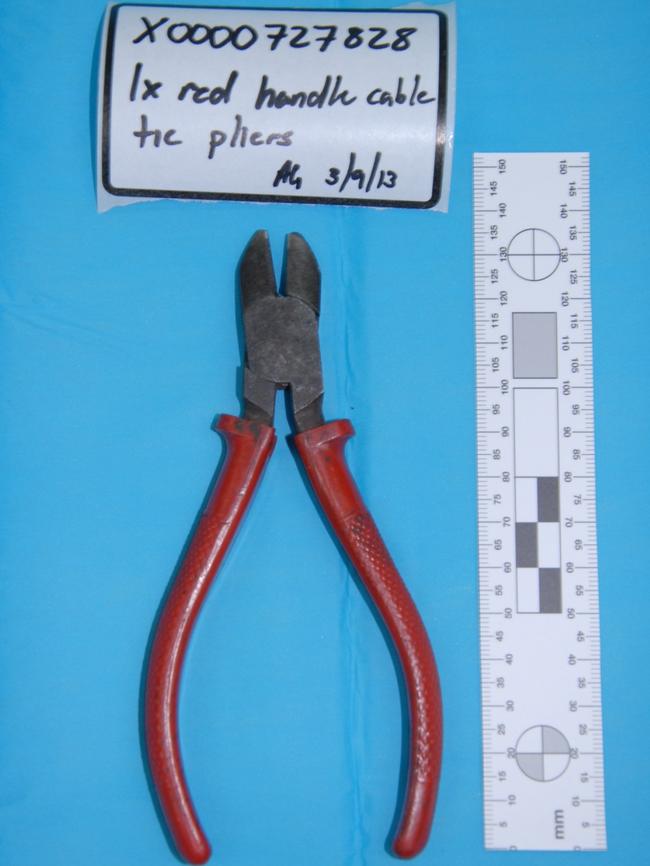

Numbers halved. At their zenith, the club had 50 chapters in NSW, its Blacktown crew among the most violent — eight of its members are currently in prison for tying up their own Sergeant-at-Arms in 2013 and beating him unconscious, the motive being a rumour that he’d cheated with another member’s wife.

(Another brief aside: Police ended up effectively saving that bikie’s life by interrupting the attack and arresting the men. They found a blowtorch and shovel nearby, suggesting a sinister end was near.)

In the Rebels’ shadow are the Comanchero, the most technologically savvy bikie gang around at the moment and the first to start using encrypted BlackBerrys to communicate.

Of all the gangs, they pose one of the biggest threats at the moment, controlling both the importation and distribution of their own drugs — most gangs do one or the other, but rarely both.

And they recruit selectively, favouring people with sought-after skills. One member, Joshua Faulkhead, was a former sniper in the military who taught gang members how to conduct surveillance and shoot weapons properly. “He fought for this country and we trained him well,” says Adney.

Factionally, the gang is divided on city versus country lines. Its Central Coast chapter is mostly comprised of ageing, white-bred Australians with greying beards and a taste for rock music. In Sydney they’re Middle Eastern and Islander by heritage, plus they’re thuggish and hot-headed.

These chapters don’t play well together, officials say. Some riders were pulled over on the F3 down to Sydney one day and, when questioned, revealed they were on their way to visit their gang cohorts in Milperra. One bikie wasn’t happy about it. “It’s like visiting the in-laws,” the bikie lamented. “You don’t want to do it, but the boss says you have to.”

Next, the Finks, who merged with the Mongols in 2013, a wholesale ‘patch over’ that routed the club of its core membership, leaving behind a few dozen Middle Eastern members banned from joining the new outfit.

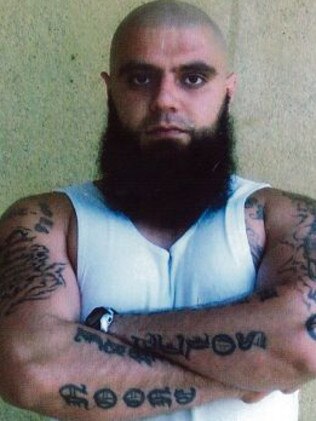

Among the spurned was Koshan Rashidi, an Afghan member who assumed control of the presidency and is now recruiting heavily to rebuild the Finks’ brand. Apparently it’s working.

With a low bar for entry, numbers have exploded. In 2017 he replaced the old logo — a happy drunk holding a beer bottle — and trademarked a new image: a beefed-up, snarling character gripping a handgun.

Rashidi became famous during one of Sydney’s most compelling gang trials when audio was played of him involved in a wild argument with Brothers 4 Life kingpin Farhad Qaumi, another aspirational Afghan crime figure, currently serving a minimum 43 years in prison.

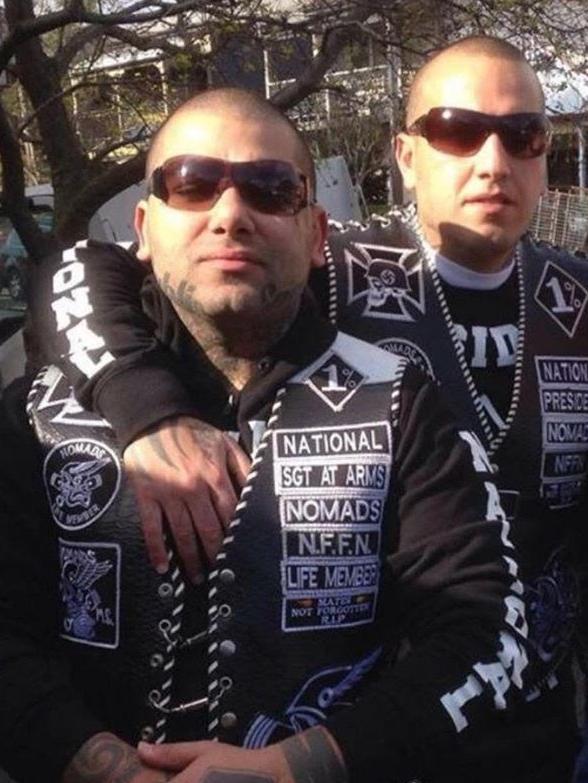

Then come the Nomads, the Hells Angels, the Bandidos, all middle-tier outfits with noteworthy idiosyncrasies.

Officials believe the Bandidos are recruiting ‘cleanskins’ (people without criminal records) to work around loopholes in the state’s consorting laws.

The Nomads are doing the same, recruiting rapidly to build their membership.

And the Hells Angels, arguably the best-known gang in the country, continue to maintain a small but powerful presence in Australia, one that rides off a notorious international reputation — worldwide their reach includes 230 chapters across 27 countries and a legal arm that has successfully sued multinational corporations to protect their registered trademarks, namely their infamous “Death Head” logo.

They have tended to avoid a national leadership like other gangs, but prominent figures include Angelo Pandeli and the soon-to-be-deported Felix Lyle.

Christian Birch, the Hells Angel I spoke to, said: “There’s no National President, as such. Each chapter’s run autonomously. It’s a franchise — it’s entirely up to you how you use your business.”

The Lone Wolf get an honourable mention here. They’re the quiet achievers of the bikie world; small on numbers but sophisticated in their business operations, dealing only with a close and trusted circle of suppliers. According to law enforcement officials, this has made them difficult to penetrate.

It goes without saying there are many reasons why people join outlaw motorcycle gangs.

It’s easy to see why the culture would attract people feeling dissociated from society, or searching for a father figure, or in need of some type of adventure, which is pretty much why we join clubs in the first place, social or criminal.

Birch, the Hells Angel, says: “It’s the notoriety, being a part of something that's infamous. The normal public have a fascination with it, otherwise your editor would tell you not to waste your time writing about us.”

Warren Gray from the Australian Crime and Intelligence Commission tells the story of a gang member he encountered during one of his agency’s powerful coercive hearings.

(This involves putting someone in a de facto courtroom full of cops and lawyers and asking questions that, if not answered truthfully, can end with jail time).

When the hearing was over, Gray got talking to the bikie and asked him, out of curiosity, why he joined a gang in the first place.

The bikie said he first tried joining the army, but a criminal record ruled him out. It was the same story with the police force. In the end, he had no other options. “That’s why I joined a gang,” he said.

Tim Watson-Munro, a court-appointed psychologist who’s worked with gang members for the past 25 years, says it comes down to a feeling of appreciation. “We want a sense of belonging,” he says. “And if they [bikies] don’t get it in the broader community, they’re going to be attracted to gangs.”

One obvious perk to being a bikie is the sex and the women, the strippers and molls, the stunning blondes and brunettes who always seem to be hanging around tough or tough-acting gangsters way below their league.

The phenomenon is undeniable, says Deb Wallace, the Gangs Squad’s commander: dishevelled, overweight and utterly ordinary-looking bikies walking down the street with gorgeous-looking women on their arms.

“It never ceases to amaze me,” she says, pointing to the cars and the bling and the misguided sense of status as possible explanations for their attraction. The relationships tend to be short-lived though, she adds, often going “pear-shaped” due to police busts or instances of domestic violence, which happen from time to time.

The official number of bikie related DV cases isn’t clear, but Raptor officials claim hundreds of bikies are currently subject to orders or going through the court process. Wallace suspects under-reporting in this space, mainly because victims are generally too frightened to come forward.

She’s a striking figure at the Gangs Squad, renowned for her stiletto heels and colourful dresses.

Her position’s a management role, very senior, and yet she’s been known to join surveillance crews on 3am operations, or turn up to house raids for big arrests, or meet directly with criminals for investigative purposes.

(In 2014 she agreed to visit Brothers For Life kingpin Farhad Qaumi as he languished in prison. “He felt that we understood each other and had a mutual respect for each other and that we were ‘soldiers’ together ... which was misguided,” she says.)

Criminals call her ma’am, and for the most part treat her respectfully. But there have been unpleasant moments. Not long ago a senior Nomad, Moudi Tajjour, then the gang’s vice-president, posted a disparaging remark about Wallace on Instagram.

“He said something like: ‘We have to go on a date, but you need to lose weight first’,” says Wallace, who laughs about it now and says it’s all bygones.

But David Adney, Raptor’s commander, didn’t see the funny side. When word filtered through about the incident, he sent officers to Tajjour’s house and made sure there were consequences. “We don’t take kindly to those sorts of things,” says Adney, who, when asked clarify what happened, simply said: “He got targeted.”

Tajjour ended up apologising to Wallace and deleting the post. He says he resisted at first, but agreed to after meeting Wallace by chance at a cafe.

“I was out of line,” he says, when asked about the matter. “I ain’t embarrassed of saying sorry to a woman I disrespected.”

He also says he’s no longer part of any outlaw motorcycle gangs, mainly due to the police targeting, which saw him raided and “pulled over seven days a week”.

“In life you get over childish ways, I guess,” he says, explaining the decision. “They know I’ve walked away. This is a positive thing in my life. (It) shows if you walk away police do leave you alone.”

Curiously, the bikie world isn’t as faithful to the old mafia trope of keeping long-term mistresses on the side. Tony Soprano and his crew kept “goomahs”, as they called them, but they had strong wives and fiancés waiting for them at home, women whom they listened to (sometimes), or occasionally sought advice from.

Bikies seem to have fewer matriarchal figures. One reason for this might be the constant patching-in-and-out of the gangs, says Wallace, or their tendency to deliberately keep women at a distance from gang business.

Women aren’t invited to the weekly ‘church nights’, for example, and the only time they really figure in gang activities is if they’re smuggling drugs into prison, or taking the fall for a crime.

“Time and time again bikies blame their wives and they just take the rap,” says Adney, recalling a Rebel named ‘Fat Pete’ (real name: Agapitos Megaloudis) who made his girlfriend collect a shotgun for Raptor officers during a raid on his house in Kurnell.

The woman acquiesced, fetching the weapon and implicating herself in a crime. “That really got under my skin,” says Adney, who rarely loses his cool but let fly at Fat Pete that night. Instead of charging the woman, Adney used his discretion and let the matter slide.

But perhaps the most powerful reason why young men join gangs isn’t in the women or the money or the status. It’s probably more abstract than that. It’s apparent in the handful of motifs that emerge during routine criminal trials: the difficult upbringing, the bullying at school, the language barriers, the drug use, the lack of role models and absent fathers.

Judges calibrate their sentencing based on these circumstances but many in the community, police especially, would suggest more nous could be applied.

Consider:

From the June 30, 2017, sentencing of Blacktown Rebels member Joshua Achampong, involved in the severe bashing of his chapter Sergeant-at-Arms: “The offender reported his father was largely absent during his upbringing. He described the club as acting as an alternative family.”

From the sentencing of Blacktown Rebels member Aaron Ferguson, same offence: “The offender described his mother and stepfather as ‘junkies’. He said, on reflection, in the absence of a father he ‘was always looking for that fatherhood or brotherhood’.”

From the March 2, 2012, sentencing of Comanchero member Christian Menzies for his role in the 2009 airport brawl: “The absence of his father left him with feelings of abandonment. ‘Attaching myself to a group of men made me feel important, accepted, strong and cared for’.”

From the July 26, 2011, sentencing of Comanchero member Tiago Costa, same offence: “He was ‘living the single life with the boys’ and ‘would go out partying, drinking and taking drugs’. He described this as ‘a fake lifestyle’.

If you think about a bikie gang as a corporation — a comparison that isn’t hard considering they hold Annual General Meetings and have ‘Treasurer’ and ‘Secretary’ positions — then it’s easy to see how their clubhouses and motorbikes and patches and leather jackets are all symbols, no different to the Nike logo or McDonald’s golden arches; they’re manipulative in subtle ways, a quasi-marketing strategy used to lure the vulnerable with messages about community and warmth and camaraderie.

Guys who were drawn to the gangs on this basis tell a familiar story once they’re out. They talk about being baited.

They say as youngsters they would see club members riding through their town or city and think, ‘Wow, I’d like to be part of that’, which would inevitably lead to hanging around the clubhouse and getting invited to the parties, the kind where big friendly guys slap each other on the back and call each other “brother”. Through the lens of low self-esteem or just generally wanting to belong and be accepted, these men appear role model-like.

The drinks are usually free. Good times are had. A stripper gets called over and lavishes attention on the ‘mark’ to make them feel important. Yes, ‘mark’, because according to Raptor staff this is all a big con-job to make the recruit feel accepted and part of something they’ve never had before, all of which, in worst-case scenarios, comes crashing down a few weeks later when they’re in way over their head and being asked to shoot up a house, or hold some drugs, or take the fall for a crime. Many end up sitting in a prison cell with no one is coming to visit them.

“You need to understand,” says Darren Beeche, the tactical leader. “A lot of them don’t want to be in the gang anymore. They got sucked in. They’ve seen the damage it’s caused. And they want to get out, but they can’t because it can cost an exorbitant amount of money and risk to their safety.”

This is Raptor’s next frontier: collaborating with bikies, helping them escape from their gangs, a partnership that looks and sounds more like social work than police work.

This wouldn’t have been possible a decade ago but now, because of the consorting laws and the clubhouse closures and the deportations and the thousands upon thousands of arrests that have fractured the gangs and their hierarchies, it’s become a promising anti-bikie strategy.

Of course, it’s not a simple process, and for obvious reasons Raptor staff don’t talk about the tactics.

Suffice it to say that consorting laws are useful in this space — ordering someone not to hang out with fellow gang members can provide a useful cover story to create distance.

The point is you can’t just walk away from a bikie gang. Once you’re in, there are rules about leaving. Most gangs have a $10,000 exit fee. Some force members to hand over their motorbikes. Tattoos have to be removed (and this is sometimes done by force). One guy took a doctor’s note to his chapter president explaining that he couldn’t ride anymore because of a bad back.

Some gangs have a ‘retirement’ option for long-serving members. In the Hells Angels, exiting on good terms means tattooing your leaving date on your body. Some gangs also ‘bash out’ their departing members.

But extracting gang members is only half the equation. Stage two is stopping the recruitment, or stemming it at least, targeting the feeder groups that cultivate and groom teenagers, not unlike ISIS and its network of emissaries operating over the internet.

Each club has a support outfit: the Bandidos have the ‘Fat Mexicans’; the Lone Wolf have the ‘Coomicubs’; and the Hells Angels have the ‘Red and White Devils’. These are all street-level clubs, some of which have been sighted targeting kids at school gates, says Senior Constable Nathan Trueman, a tactical officer with Raptor.

In response, Trueman is now driving a program that he hopes will send Raptor staff into high-risk schools to speak directly to teenagers at risk of gang recruitment, an idea already receiving support from his commanders. He’s been sent to the United States in preparation, to Arizona and North Carolina, to study local anti-gang initiatives that might be useful here in NSW and beyond.

A draft proposal for the program has already been presented to the NSW Police Force’s Youth Command.

Trueman says there will always be a percentage of kids completely enamoured by gang symbolism, who’ll become bikies regardless of any intervention. There are also kids on the other end of that spectrum, those who are totally disinterested in gang culture and pose no risk of being recruited.

“It’s that middle portion,” he says, “the ones who could go either way — that’s our target audience.”

The last question I ask almost everyone I speak to is whether the ‘airport brawl’ could happen today. The answer is no, it wouldn’t. The airport is drum tight now, full of security alerts and heads-ups for law enforcement.

Intelligence has dramatically improved too: warring bikies would barely make it out of their houses, let alone to the terminal, before getting tripped up by Raptor. And bikies don’t walk around in large numbers like they used to.

Their meetings are shrouded in secrecy, a result of the consorting laws, which is why they seek privacy in country towns like Mildura.

But perhaps the biggest reason why an airport-style brawl wouldn’t happen today is because the bikies have devolved from the powerhouses they once were. Without their motorbikes and colours and patches and clubhouses, they’re more akin to street crews than gangs.

They exist, but they’re not as visible. They’re still powerful, but out of sight. Whatever they’re doing, it’s more discreet. And while that might create new challenges for law enforcement, it’s a measure of success for Strike Force Raptor. The mission’s priority was always to reduce the violence between gangs and stop bikies from bothering people. If you haven’t seen one lately, that’s probably because it’s working.

So are the bikies finished?

Darren Beeche says he’s been told as much in private, though he and his colleagues are cautious about making declarations. “I’ve had a number of high-ranking bikies tell me that,” he says. “We haven’t won the war yet but we’ve made a significant change [in the community], one that I would have never conceived when we started.”

There’s another side to this perspective, however, and it comes from a lawyer who deals routinely with bikies. He says Raptor’s successes are

obvious, but they have displaced the problem, creating a stronger, savvier criminal that ultimately will prove harder to catch. “When you kill all the lions,” he says, “you get a plague of hyenas”.

David Adney, always cool-headed, isn’t fussed by that. “We’ll be there,” he says. “And they’ll end up in jail.”

► PART ONE ► PART TWO ► PART THREE ► PART FOUR

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout