THERE hasn’t been a full-scale ‘bikie war’ since 2012 when a young drug dealer aligned to either the Nomads or Hells Angels (few people really know) crossed a highway in southwestern Sydney and walked into rival territory to sell his product, a transgression that led to 12 drive-by shootings, three firebombings, and nearly two dozen arrests on both sides of each gang.

Prior to that there’d been a similar war between members of the Bandidos and another gang, Notorious, but it wasn’t as epic — Notorious demanded compensation after one of their men was bashed by the Bandidos, which led to a Notorious-linked inmate being bashed in prison, which led to a drive-by shooting on a house in Auburn owned by a Bandidos member, which ignited tit-for-tat shootings all over southwestern Sydney.

The whole thing lasted a couple of weeks and ended up becoming part of a general litany of shooting incidents that fast-tracked the muscular laws that have helped make Raptor so successful.

Today, the only public-place violence we see tends to involve the usual flash-in-the-pan skirmishes between gangs, like the issue up at Tweed Heads.

But in the main, ‘bikie wars’ aren’t the problem anymore.

Some facts. More than 1315 guns have been seized by Strike Force Raptor since its inception, amounting to about three guns per week, an extraordinary number for a single unit.

More than 3700 people have been put before the courts. More than 60 clubhouses have been closed – from high-walled acreages in western Sydney to humble tin sheds in Broken Hill, to industrial estates with blacked-out windows and surveillance cameras on the Central Coast.

Roughly 900 search warrants have been carried out, an intense work-tempo equating to about two raids per week — most commands would be lucky to hit two raids in a month.

Think about that for a second: a few dozen cops up against thousands of gang members, some of whom are skilled at counter-detection and have been doing this kind of thing for decades, their territory spanning everything from big cities like Sydney to regional centres like Tamworth, or Newcastle, to distant communities in the backblocks, all of which, let’s be unequivocal, is way too much turf for one small squad to cover.

There’s a high bar and long waiting list to get accepted into Raptor.

Officers have to sit several interviews. Then they’re trialled and observed by commanders over a couple of weeks. Those with promise are signed up.

To make the tactical team, they have to spar with its leader Darren Beeche, an accomplished boxer and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu practitioner – it’s an unofficial induction, like a fight club, and he never loses, even on guys twice his size. Some cops are headhunted to join.

There was a guy working in uniform one night at Ashfield Local Area Command who heard what sounded like gunshots in the distance.

Twelve years in the army had trained him to listen out for different bullet calibres and these definitely sounded like 7.62 bullets, capable of breaching tank armour.

With a colleague, he hopped in a car and found the spent shells in a nearby park, which helped with the follow-up investigation. Adney heard the story and called him soon after with a job offer. Today, he’s Raptor’s firearms expert.

There’s also a fraud expert and a snake handler (bikies have a fascination with exotic pets).

But importantly, Raptor is a culture, an attitude.

It’s a unit that attracts a particular breed of cop. The tactical teams are strapping, meat-eating Alphas whose natural tension release is to put a battering ram into a front door.

But there’s diversity across the unit: accountants, indigenous officers, a handful of women, deeply religious men. These are all cops happy to put themselves in front of an oversized bikie, or several oversized bikies, so civilians don’t have to.

There’s a chivalry at the heart of this that’s difficult to explain, a commitment to a moral code that’s made bikies particularly cautious.

For a glimpse of this caution, consider the response from a high-ranking gang member asked to participate in this story. He declined. “I have enough dramas with police forces,” he said. “The last thing I need is to annoy [Raptor] by commenting on anything.”

What’s worth remembering, too, is that it’s taken eight years of dawn raids and postponed holidays and missed birthdays for Raptor officers to reverse the status quo around Sydney.

People forget that there was a time when bikies would ride around with a gun down their pants, or put a man in hospital for the fun of it, or stand over café owners for a cut of their weekly earnings, or rack up parking fines and refuse to pay; all of this without fear of any consequences— because before Raptor there weren’t any, really.

“They felt they could do anything,” says Adney.

And so in response to Raptor the bikies have evolved.

They’ve become slick and sophisticated entities with websites and offshore leaderships and encrypted communication methods that make catching them a lot harder.

On paper this would appear to be a bad outcome, one that’s pushed the bikies underground and given rise to a more complex, longer-term problem.

But maybe it’s also just a natural progression in the cat-and-mouse game criminals and cops have been playing for generations.

But to understand where the bikies are heading, and what they’ll look like in the future, we have to look at the story so far.

Like: how did the bikies keep their racket going for so long? From where did they draw their power? Why did we as a society accept this standard? And at what point — and how — did they lose this upper hand?

This is what happened. Up until 2009 and what is now known as ‘the airport brawl’, there were hundreds of investigations into gangs like the Rebels, the Hells Angels, the Nomads and the Bandidos, but they revolved around a handful of characters and didn’t achieve results in any grand or meaningful way.

Something called Operation Ranmore racked up triple-digit arrests and charges in 2007 and 2008 by making local cops at every police station knuckle down on bikies.

The results looked good on paper, but the practical effect was negligible.

Those arrested weren’t the shot-callers of any particular gang.

They were ‘nominees’ or ‘associates’ who carried out crimes to prove allegiance and earn their ‘colours’, which, by the way, used to be a big-deal achievement in the bikie world and took years to accomplish but can now take just a couple of weeks, even less in some cases, depending on how much recruitment a gang needs at any particular time.

Older gangs will still make a person work for their patches, but gangs seeking notoriety are totally relaxed about it. And if you’re wondering what’s caused this diluting of standards, it can pretty much be traced to one man’s induction into the bikie subculture; most people agree it was his work that changed everything.

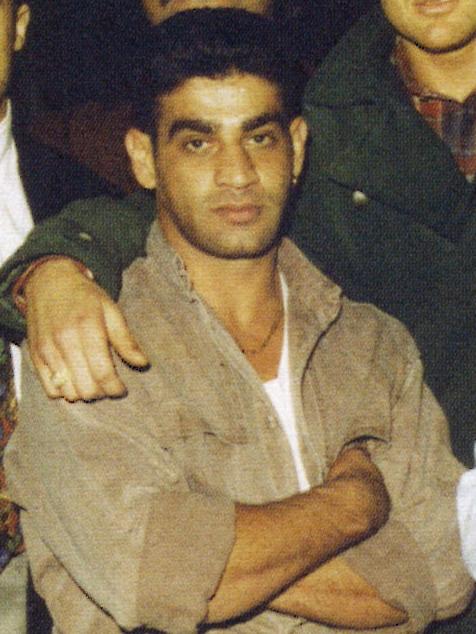

That man is Sam — Hassan ‘Sam’ Ibrahim, brother of nightclub owner John Ibrahim and lifetime member of the Nomads outlaw motorcycle club, the gang which recruited him in 1998.

A big deal up at Kings Cross, then a red-light district and a fertile ground for drug profits, Sam cemented the Nomads’ connections with Middle Eastern crime families and quickly rose to the rank of Vice-President within the gang’s Sydney West Chapter.

Then he splintered off and started his own chapter in Parramatta. People familiar with the story usually roll their eyes at this point because everything went south after that.

Gone were decades of rules and traditions that bikies had sworn to uphold — the extended nominee periods, the lengthy approval processes, the ironclad edicts about members having to own and ride a motorbike, the unspoken codes about never cooperating with police or switching gangs — and in came the petty thugs of Middle Eastern and Islander extraction, criminals who didn’t care about anything and moved between gangs like they were trying on coats in a thrift shop — Bandidos colours one day, Hells Angels colours the next.

This would have been unthinkable in previous years.

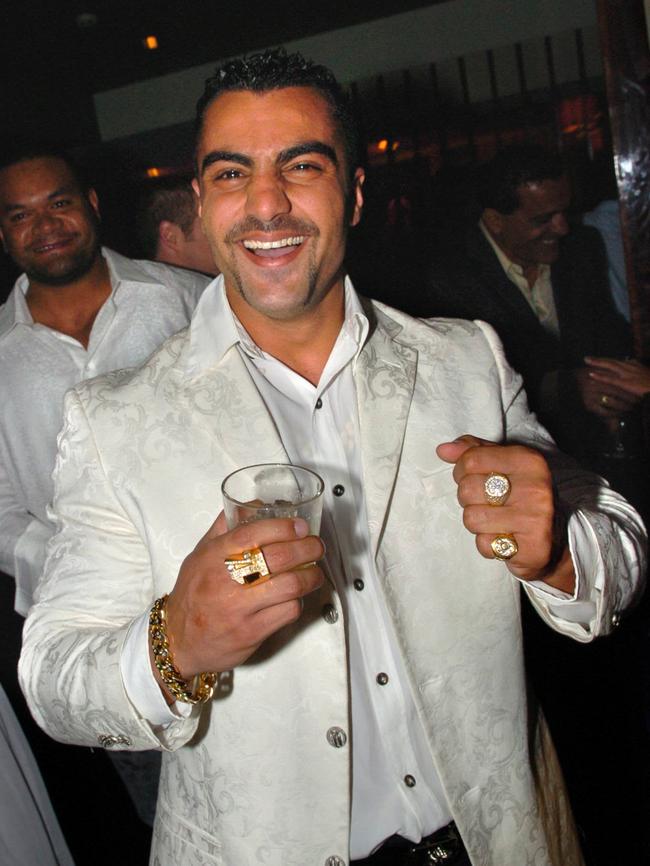

But that’s how the modern-breed of bikie was born. Body conscious, impeccably groomed, they donned Gucci sweaters, Versace shades and gleaming white Nikes.

Many didn’t ride a bike. They were cartoonishly muscular from steroid use, which made them aggressive and unstable.

“Sam single-handedly ruined the Australian motorcycle club culture,” writes John Ibrahim, Sam’s younger brother, in his recently-released autobiography. “Before my brother joins the Nomads, there are no Lebos or coconuts in that culture: it’s beer-drinking Anglos watching strippers and riding their bikes. Sam brought a whole new level of intensity to those clubs, and they’ve expanded and changed because of it.”

A former Gangs Squad commander told The Sunday Telegraph in 2013 that steroids and peptides were being found in roughly 95 per cent of Raptor search warrants, which, it was surmised, was a likely cause for many of the drive-by shootings taking place around Sydney, shootings that usually came down to a handful of motives, usually wounded egos or beefs over territory.

But even a chance encounter was enough to trigger mayhem between rival gangs, the most memorable being the one at Sydney Airport in early 2009, which ended up becoming a tipping point in Sydney’s underworld history.

For the first time in decades, bikies dominated the national agenda, triggering crisis talks in Canberra and debate in federal parliament.

The prime minister got involved. Inquiries were launched. And it all came down to a brawl, a very public one, a brawl that blew up so spectacularly that it sent political fallout across the country, shattering the bikies’ image as good old boys and harmless, anti-social tough guys who live to ride.

When the dust finally settled, the bikie universe had changed irrevocably.

► PART ONE ► PART TWO ► PART THREE ► PART FOUR

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout