The genius frenemies who changed the course of modern art

A stunning new art exhibition takes us inside the contradictory, affectionate, mutually suspicious and often rude tug-of-war that propelled two titans of modern art to the top of their game

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

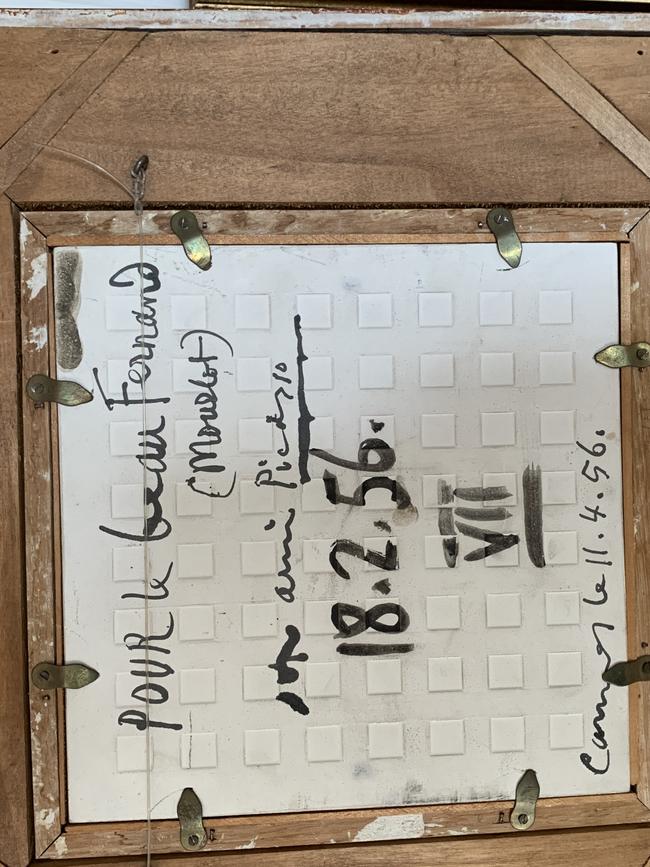

The framed ceramic tile sits in a cluster of other small artworks in a sunny apartment in Paris.

If it weren’t so beautiful, you might overlook that tile. Manners would certainly prevent you from picking it up and noticing the signature of Pablo Picasso on the back.

But if you did, you’d be holding more than just a tile. You’d be holding a key to a contradictory, affectionate, mutually suspicious and often rude tug-of-war that propelled the two titans of modern art to the top of their game.

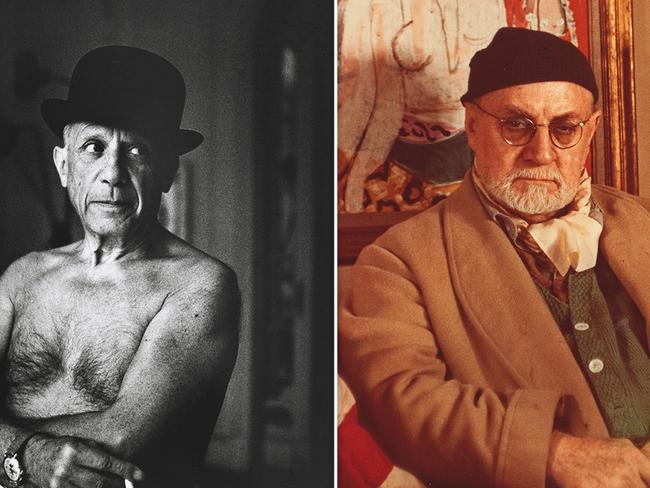

Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse met in Paris in 1906. French master Matisse was 12 years older than the Spanish genuis, and a loner by Picasso’s rowdy standards. Yet they were friends and sparring partners until Matisse’s death in 1954.

Along the way, their personal interactions and professional rivalries make a complex story, one that is told in the exhibition Matisse & Picasso, which opens this week at the National Gallery Of Australia in Canberra.

DEATH OF A MASTER

Of all the mysteries of their long relationship, none might seem more baffling than Picasso’s reaction to his old friend’s passing. And here’s where the tile comes in.

When Matisse died, his daughter rang to inform Picasso. But a servant said Picasso was having lunch and could not be disturbed. After the third call, the message was relayed: “Monsieur Picasso has nothing to say about Matisse since he is dead.”

It was a tremendously hurtful reaction. But the man who owns the Picasso tile is not surprised. Jacques Mourlot was very fond of Picasso, but he knew that the artist was completely self-centred and very afraid of death.

Jacques Mourlot’s father Fernand owned the legendary Atelier Mourlot, whose artisans worked with most of the era’s greatest names when they were making lithographs and engravings. Jacques, now in his 80s, knew both Picasso and Matisse because he was employed in the family firm.

MORE FROM ELIZABETH FORTESCUE

New Breed choreographer confronts future

Talented kids school us in the art of rock

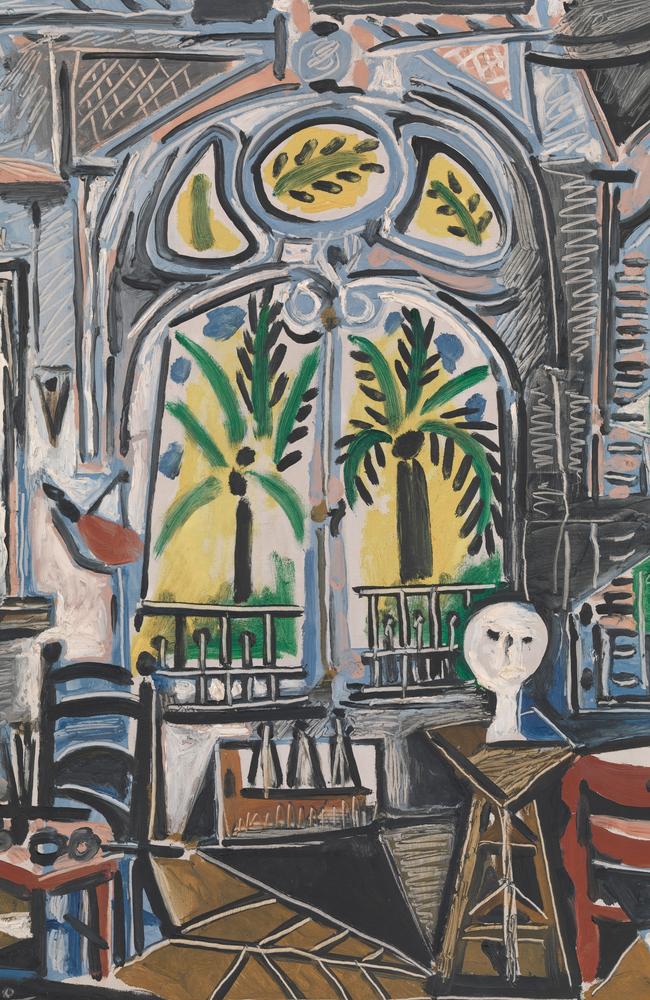

While Picasso’s reaction to Matisse’s death seemed cold, perhaps his true feelings were expressed in an image that he painted over and over again the following year. It’s the image on the tile, and it’s repeated in a painting titled The Studio, which London’s Tate Modern museum is lending to the Canberra exhibition.

In the picture, Picasso painted the view of palm trees from the windows of his home, Villa La Californie, in Cannes.

The whole effect is decorative and opulent, like a Matisse. The entire series is a clear homage to the older artist, feels NGA head of international Jane Kinsman, who curated the exhibition.

After Matisse died, Picasso knew his own life and art could never be the same, says Laurent Le Bon, director of the Musee Picasso in Paris.

“Picasso used to say, ‘when one of us will die there will be some things that the other couldn’t tell to anybody’,” Le Bon says.

MEETING OF TWO GREAT MINDS

After Matisse and Picasso met in 1906 at a Paris exhibition, they started meeting at the Paris apartment of American collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein, who would help make both men famous.

By 1909 the two artists were making money. In 1918 the Parisian art dealer Paul Guillaume organised the first joint exhibition of their work, one that established the narrative of their rivalry. The poet Apollinaire’s essays in the catalogue clearly favoured Picasso, helping establish a pattern whereby Matisse was seen as merely decorative while Picasso was ground-breaking and vital.

When London’s V&A museum was mounting a similar joint exhibition in 1945, Matisse fretted: “I can imagine the room with my pictures on one side and his on the other. It’s as if I were going to cohabit with an epileptic. How well-behaved I will look (even a bit silly to some) next to his pyrotechnics.”

The reality was that both artists needed each other.

“For half a century, they spurred each other on to do things that might not have been possible without the other, like top-level athletes who set the pace for each other,” Jack Flam wrote in his book Matisse And Picasso, The Story Of Their Rivalry And Friendship.

Matisse once said only one person had the right to criticise his work, and that was Picasso. And Picasso said: “All things considered, there is only Matisse.”

PICASSO’S PERSONAL TREASURES

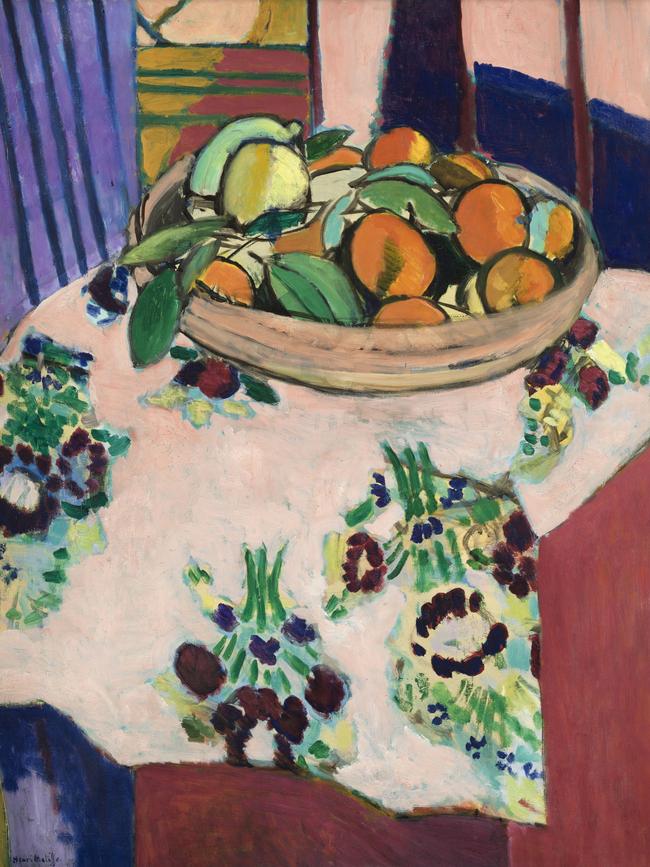

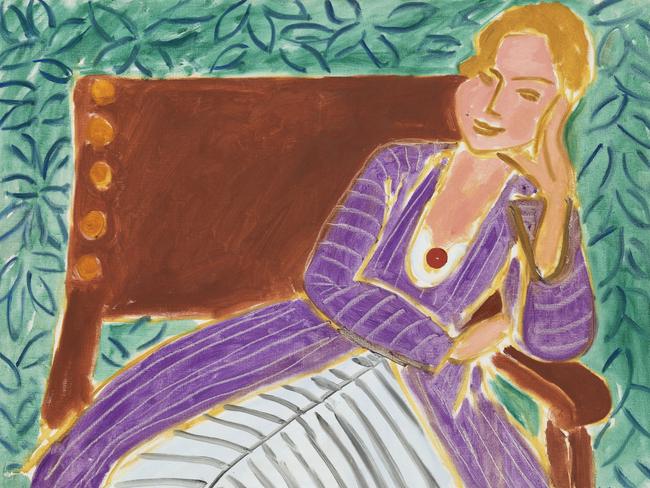

Both artists were known to sketch from each other’s paintings, each trying to get underneath the skin of the other. They also exchanged pictures. The NGA exhibition will feature two Matisse paintings that were in Picasso’s personal art collection when he died in 1973. They are Still Life With Oranges, painted in Morocco in 1912, and Seated girl, Persian dress, 1942.

“Still Life With Oranges is the masterpiece of the private collection,” Le Bon says.

Wherever Picasso was living, Still Life With Oranges had pride of place. Rather sweetly, Matisse would send Picasso a basket of oranges every New Year. Picasso would point them out to visitors, saying “these are from Matisse”.

These moments of affection did not prevent the two artists from enjoying a bit of mutual suspicion.

“I have not seen Picasso for years. I don’t care to see him again. He is a bandit waiting in ambush,” Matisse wrote to his daughter.

Matisse was not just being paranoid. Le Bon believes Picasso took more from Matisse than the other way around. Kinsman says Matisse was particularly concerned Picasso would throw his creative net around Matisse’s paper cuts. These were artworks made from coloured and cut paper that assistants arranged according to the master’s instructions, issued from bed where Matisse was confined in old age.

WORKING WITH GENIUS

Jacques Mourlot remembers taking proofs of prints to both Matisse and Picasso. Picasso adored making prints, and would work at the Atelier Mourlot for 12 hours a day, testing out radical ideas and pushing the technicians to their limits. Picasso respected the artisans and got on well with them, and he worked quickly.

Matisse, however, was not friendly and “everything was difficult”.

“He had to do everything 10 times,” Mourlot says.

Many of the print works in the Canberra exhibition were made at the Atelier Mourlot.

Myth and legend swirls around the towering figures of Matisse and Picasso. But Le Bon believes the story that Picasso and his friends threw suction-capped darts at a Matisse painting in about 1907.

As for Picasso likening Matisse’s interior design for the Rosary chapel in Vence, France, to a “bathroom”, we have the clear-eyed testimony of Picasso’s former partner Francoise Gilot. It’s true.

Matisse & Picasso features works from lenders all over the world, including the Art Gallery of NSW, whose Picasso, Nude In A Rocking Chair, 1956, is recognised as a homage to the dead Matisse.

Matisse & Picasso, National Gallery of australia, canberra; December 13, 2019 until April 13, 2020, nga.gov.au

The writer travelled to Paris courtest of the National Gallery of Australia