ANDREW “Twiggy” Forrest is fronting an audience of 40 and for once it’s not him calling the shots. Doing the grilling are the nation’s brightest brains on fish and the oceans.

As Forrest answers curly questions in his appeal to do a doctorate in marine ecology, he wonders whether the gathering would be so large and tough had this billionaire not walked through the door.

A maverick, a mining magnate and a serial philanthropist, Forrest at 57 is worth $5.1 billion.

“Of course I am an unusual student and, you can imagine, that room’s full,” Forrest says. “It was like open season, 30-40 people could ask whatever they wanted.”

We know plenty about our pristine coastline, he says, but his PhD would delve into the most under-researched aspect of marine life — beyond the visible horizon and out into the deep blue.

“I’m sure there were people there who wanted to come on to trip me up … I think at the end of it people were very persuaded,” says the chairman and 33 per cent shareholder of the $13.6 billion Fortescue Metals Group.

Forrest’s research in the 2½ years since has convinced him the oceans are in dire straits, with big fish numbers down 30 per cent over the past decade due to overfishing and, to a lesser extent, pollution.

Now he wants to persuade the rest of the nation the oceans need a saviour.

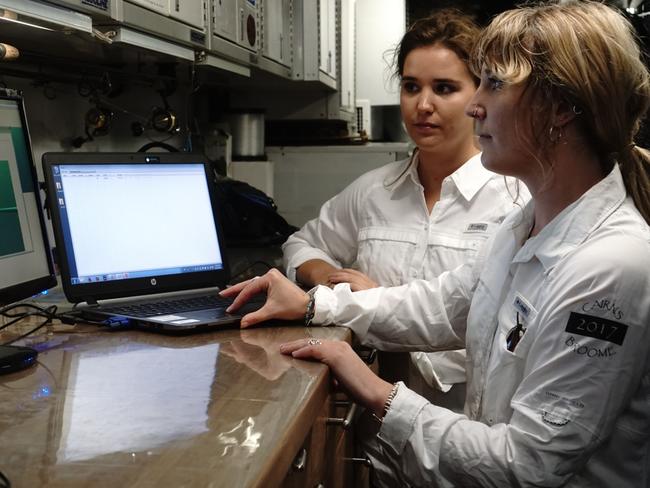

While his deep pockets and pulling power didn’t matter to the professors who accepted his PhD, they have certainly helped since. Just a week after dropping millions — he won’t say how much — purchasing the luxury marine research super yacht Pangaea Ocean Explorer, Forrest this month pulled together leaders in science, tourism and ocean transport with the nation’s media on the Pangaea to announce he would give $100 million to ocean research.

The window had come up in his diary just days before and on the eve of the announcement he ramped up the amount from the original planned pledge of $75 million.

It’s the kind of passion and generosity that has made Forrest and his wife Nicola among the most significant and high-profile philanthropists in the country.

It brings to seven the number of causes the Forrests are supporting, and comes just 15 months after they pledged the largest single philanthropic gift by living donors in Australia of $400 million to the Minderoo Foundation.

The total pledged since its inception in 2001 — “to give a hand up not a hand out” — is $722 million.

The gift also cements the Forrests’ role in a special global campaign begun by billionaire Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, The Giving Pledge, calling on rich people to give away most of their fortune. Their causes, like Forrest himself, set ambitious targets, including eradicating cancer, ending slavery and indigenous parity in work and education.

You get the feeling what Twiggy wants, he gets.

Sitting down with Forrest for this interview meant I had to make an unscheduled and undignified scramble, helped by buff crew members, from the top deck of a tender boat over railings to a mid-deck of the five-level Pangaea in challenging swell.

We were meant to be speaking on dry land after the funding announcement earlier in the morning aboard the Pangaea off Rottnest Island. But the Pangaea got delayed on the ocean when I was halfway back to Perth and I was required to return to the boat to interview Forrest.

Relaxing back on the booth Chesterfield on Pangaea’s bridge, Forrest is gracious about my brave arrival back on board. And despite wanting to speak only about the oceans, he is uncharacteristically candid about his family.

“This is a big day for the Forrest family,” he says.

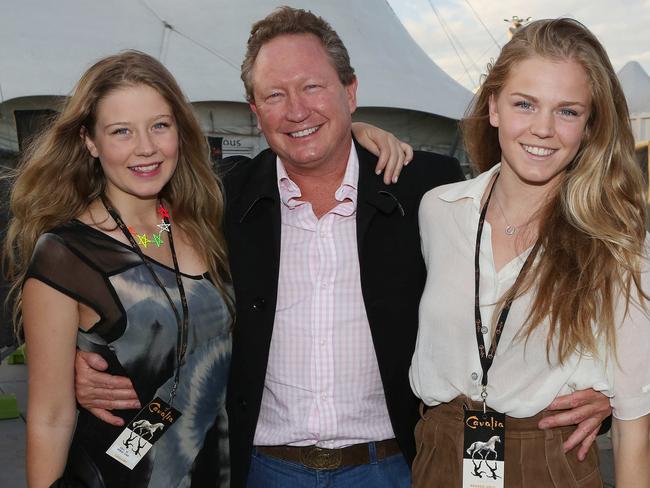

On board are Nicola and two of their three children — eldest Grace, 25, and Sophia, 22. Greeting them back on shore at Fremantle dock is his father Don. Youngest son Sydney is completing high school.

When he bought the boat Don commented that it was too big, Forrest says. When Andrew protested that it was an ice-class vessel and would go to Antarctica on research missions, his father said: “It’s not big enough.”

The family’s philanthropy began well before Forrest stepped aside in 2011 as boss of Fortescue Metals and has been developed in discussions around the kitchen table. Minderoo’s Wake Free foundation to help the 40.3 million people worldwide living and working as slaves was born after Grace, then 15, travelled to Nepal and visited an orphanage a decade ago.

When she returned two years later she was horrified to discover many of the children she met were gone and there were no records of where they were or who had them.

“It was the child-trafficking rings which Grace uncovered that drew us into it,” Forrest says.

“We were talking as a family about the fact that I would eventually step down from being chief executive of Fortescue, which was a really big step for me and the family, and pursue modern slavery.

“There was a lot of kitchen table talk that that could be dangerous. This would be the first global major challenge against modern slavery, we’d be pushing against one of the biggest illegal industries in the world and that could have a risk for the family.

“Grace said: ‘This is what I, as Grace Forrest, am going to devote my life to’ … So the family said, ‘OK, there’s two of us now so let’s do it’.

“Grace has been passionate about it ever since and I’ve done everything I can to support that passion through starting the Walk Free Foundation with her and then through the very serious measurement — which Grace got going while she was at school — of the Global Slavery Index and others.”

Grace launched the latest Global Slavery Index in New York recently, estimating every year $12 billion worth of goods imported to Australia are at risk of slavery in their supply chains, with fashion among the top five industries most exposed to using slave labour. Forrest says from a young age Grace had a keen social conscience and in primary school befriended a girl who had been adopted into an Australian family from Ethiopia.

“The two of them used to raise money for kindergartens and playgrounds back in Ethiopia. We were able to sneak in to the school and say … ‘If you raise X someone else will match it’. And she never knew to this day who the matcher was. She’ll probably figure it out. She had that bent from her very early childhood and we used to encourage it.”

Forrest says middle child Sophia as a teenager was keen on psychology, successfully petitioning her high school to offer the subject and doing very well in it in her final exams.

“Then she took a year off, came back from that year and said, ‘I want to be an actor’.

“I said: ‘Well, pursue your dreams, girl. You’ll find NIDA (National Institute of Dramatic Art) or WAAPA (Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts) very hard to get into. WAAPA’s local but it’s even harder than NIDA, so have a crack but be prepared to have a plan B’.

“So she had a crack and got in. Great,” he laughs about his backfired plans.

Sophia has worked with some of the nation’s best talent in her early career, being directed by both Russell Crowe and Rachel Griffiths.

She plays rebellious teenager Debbie Hampshire in the television drama Love Child and had a small role in the post-Gallipoli epic The Water Diviner, directed by and starring Crowe.

She is playing the sister of Melbourne Cup-winning jockey Michelle Payne in the Griffiths-directed Ride Like A Girl, starring Teresa Palmer and Sam Neill.

“She loves it. She’ll get an acting role and as part of her preparation for the person she’s portraying she’ll actually write diaries as though she is that person before she goes on screen. She adopts that person’s heritage, persona and then mimics it. Really does her homework,” Forrest says.

He says he is not concerned about Sophia working in an industry that had its ugly underbelly exposed in the #metoo movement for mistreatment and exploitation of female actors, especially those new to acting.

“She’s a very strong kid, like Grace. I would feel trepidation for anyone who tried to take advantage of their position over Sophia.”

Forrest says his love of the ocean began when he was an 11-year-old boy, camping on the coast at the family’s remote Minderoo Station in the Pilbara in Western Australia. For years when relaxed and happy on family holidays, he would tell Nicola of his hankering to study the oceans.

“Finally she said, ‘Well study the bloody oceans’,” he says.

Forrest has sometimes in the past been criticised for over-egging the argument in his passion to present a persuasive case. At the ocean donation announcement he dubs those who don’t value marine parks and the protections they provide as “the believers in a flat Earth”.

He wants the government to drop plans to lift bans on fishing and mining in marine parks across the nation, claiming it paves the way for Japanese and Spanish commercial fishers who have already pillaged their own oceans to come here and deplete ours.

“If you roll back marine parks, you allow industrial fishing from other flag countries and when they’re subsidised by their governments to the tune of billions of dollars to fish everyone else’s waters, they’re going to come rolling in here and smash our coastlines and smash our marine parks,” Forrest says.

Liberal senator Matt Canavan, whose state of Queensland stands to benefit from the roll-back, says the plan allows Australians to access local seafood caught in a sustainable way.

“The extremists calling for the banning of fishing across large parts of Australia’s oceans don’t seem to be also arguing for the banning of fish and chips. So they’re hypocritical,” Canavan says.

“If we ban fishing from large areas of Australia we will have to import more fish from overseas, where the environmental protections are not as good as Australia.”

Forrest’s new grant will fund the first global index of marine life and identify the oceans most depleted of fish, and the causes.

“We are in a serious predicament as a species of destroying the oceans like we’ve destroyed so much of the land. I feel very strongly about this.”

As for the environmental impact of his own Fortescue Metals’ iron ore mining operations, Forrest says mined land is always rehabilitated.

“You can go to any part of Fortescue now and you can tell where we used to mine because vegetation is richer. We’ve removed the hard metals — which will never grow anything — and we’ve put back the soils, aerated it and seeded it and you can tell where we’ve mined because the vegetation is better off.”

The reporter travelled to Perth courtesy of the Minderoo Foundation.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout