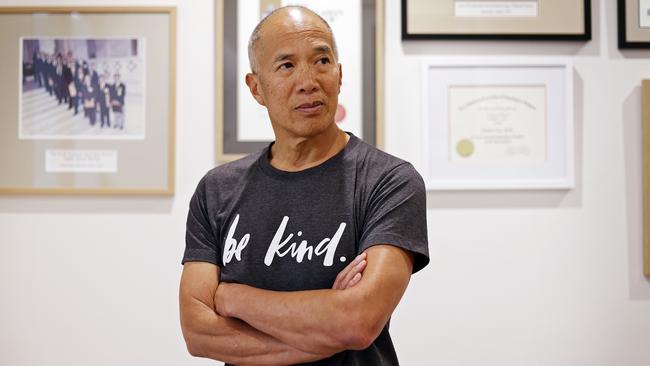

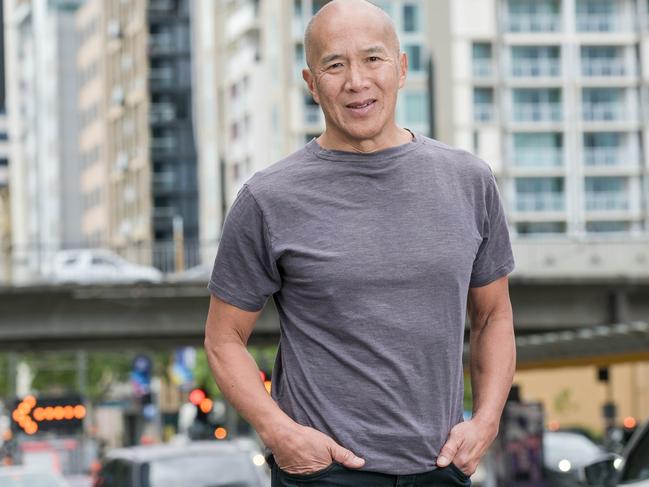

Right of reply: Dr Charlie Teo answers his 60 Minutes critics

Controversial neurosurgeon Dr Charlie Teo was hit with a barrage of accusations on 60 Minutes last week. Now, he addresses all the allegations in a frank Q&A.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Q: Do you admit you’ve made mistakes?

A: I’m human. Of course all doctors make mistakes. The only real mistake is the one from which we learn nothing. Hence, I’ve published my “mistakes”. In fact, I have published two papers specifically on the complications of surgery.

I take responsibility for my bad outcomes and of course I’m sorry for them. You would have to be a sociopath if you weren’t.

In neurosurgery, any mistake can lead to catastrophic outcomes, leaving people in a vegetative state, even death, and the surgeon must live with that every day thereafter.

I have never denied that I make mistakes, but I categorically deny the allegation that bad outcomes mean nothing to me. That’s an absolute insult and it’s simply wrong.

I don’t know any doctor that’s not personally affected when they have complications. Every doctor has complications, but what I vehemently deny is that I trivialise them and that they don’t take an emotional toll on me.

I treat all my patients like members of my family and if things go wrong, I feel terrible and if I didn’t feel terrible, I shouldn’t be in the game.

Q: People say you’re an egomaniac. Are you?

A: People who say that haven’t met me. They don’t know me. You could listen to an interview, thinking you know me, but you don’t.

As for thinking I’m the best surgeon, well yes I have to think like that. If ANY surgeon who honestly cared for their patient didn’t think they were the best at that particular operation, then they would refer that patient to the person who was the best. Therefore, almost by definition a surgeon who performs surgery clearly thinks that they do it better than anyone else. I know that I wouldn’t want my surgeon to say “I’m happy to do your operation but I’m not the best”. The first thing I would say is: “Well, who is the best and please may I have a referral to that person”.

Q: Your critics imply that you’re a money hungry person who has a disregard for human life.

A: I find this a despicable accusation and completely wrong. I’m not a money hungry person. I do four months a year pro bono work in developing countries, which means in effect I am “paying” to teach other surgeons, as well as speaking at small and large neurosurgical conferences around the world. I have spent at least 3 nights a week for the last 25 years raising money for brain cancer research. I have raised over $51 million through 3 separate charities and built the largest tumour bank in the Southern Hemisphere that is open to scientists around the world. I’m not saying I’m a saint but I’m certainly not driven by money. I strongly believe that the love of money is the root of all evil and I have lived by that mantra since it was taught to me by my mother as a child.

MICHELLE SMITH

Q: Ms Smith claims you did not remove any of the tumour and that you “operated on the wrong side of the brain” nowhere near the tumour and took normal brain tissue.

How do you respond?

A: For the record, I have never, ever operated on the wrong side of the brain in my entire career. You cannot operate on the wrong side of the brain when using the technology we had in place at the time of her surgery. It’s called Computerised Frameless Stereotactic Guidance by BRAINLAB and it does not allow the surgeon to “get lost” in the brain. She knows that and the so-called expert witnesses for the plaintiff knows that. My insurance company at the time chose to settle out of court because it appeared like the entire neurosurgical fraternity were prepared to lie to see me unfairly prosecuted. The surgical approach that I took to remove her tumour was the safest and most direct route to her lesion “Contra-lateral / trans-falcine Approach to a mesial Inter-hemispheric lesion”. Furthermore, not removing her tumour was a calculated and deliberate attempt to minimise damage given the borders of the lesion were so poorly defined. I make no apologies for the outcome of her operation. She awoke seizure-free and without any neurological problems. If I had been a less experienced or cavalier surgeon, I would have gone “searching” for the tumour and likely caused permanent paralysis given the location of the lesion close to the motor strip of the brain. She was informed that the tumour was not completely removed at the time of the operation and offered further surgery should her seizures return. She was then referred to a neurologist for longer-term follow-up and I never saw her again. The law suit was filed 18 years later.

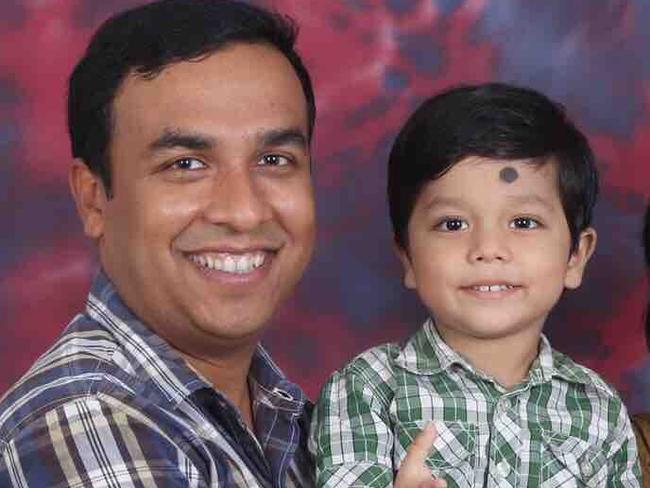

MIKOLAJ BARMAN

Q: Mikolaj’s father says you told him his little boy’s tumour could be cured despite other doctors saying it was a DIPG tumour and therefore inoperable. Multiple neurosurgeons shown the scans by 60 Minutes said it was a DIPG and when they were told a surgeon said he could operate they were “horrified”. How do you respond to that?

A: I would never have said I could cure him, but I did say that cure was possible if the tumour was focal and benign. His father wanted to do everything he could to save his little boy. I wanted that too. He was advised of the risks of the surgery, and they were very serious risks, including the chance he could die or be vegetative. His father loved this beautiful little boy and I wanted to help him. To suggest otherwise is reprehensible.

As for the diagnosis, it’s complex and has been simplified by 60 Minutes. A DIPG is often misdiagnosed. This happens in at least 10 per cent of cases and as many as 40 per cent of cases in some series. I believe it is closer to 40 per cent. This is a fatal error because once the tumour is labelled as a DIPG, the patient is given palliative care only and will likely die within 18 months, even if the tumour is low-grade. Even a biopsy showing the “typical” molecular abnormality of H3K27M mutation, isn’t necessarily diagnostic. Mikolaj had a definite focal component to his tumour and although operating on the diffuse part would have been foolish, he had much to gain from removing the focal part. The potential benefits included, obtaining tissue for diagnosis, prognosis and the possibility of admittance to a clinical trial, reducing the bulk of the lesion so that he could come off steroids, longer survival and making radiation more effective.

Q: What do you say to the claim that the “futile and expensive” operation “catastrophically damaged” him?

A: This is a complete lie. I do not operate on DIPG’s as they are inoperable. However there was a chance that I could remove at least part of it and I actually did. Why he awoke with neurological problems will never be known but I take full responsibility that it was likely to have been me being too aggressive with my resection. The brain stem is such an eloquent structure that even 1mm can be the difference between a normal outcome and a devastating outcome.

Q: They say they paid a quarter of a million dollars for the rest of his short life in a room staring at a ceiling, only means of communication was blinking. The father says he regrets agreeing to the surgery and you “spoiled” their last 13 months. Do you regret operating?

A: I can’t make comment about the cost of the operation and care thereafter but I can say that my fee was only a small percentage of that total cost. At the end of the day this is why brain surgery has the reputation that it has. It is totally unforgiving and one small error of judgment can change the quality of life of the patient. The father was fully aware of the risk of surgery. He was fully informed by me and the surgical team in Singapore. I remember the case very well and how delightful and beautiful Mikolaj was. I remember the love of the father and I remember promising to treat him the way I would my own child. I know the father is angry, but he shouldn’t be. Both he and I went into that operation with Mikolaj’s best interests in mind. Furthermore, his tumour was so bad that the terrible neurological problems that he had at the time of his death, he would’ve had anyway from the tumour, not just from my surgery.

Q: Would you operate if you had your time again?

A: Yes I would, as there have been many documented cases where the (scans/biopsies) have been wrong, leading to a misdiagnosis.

BELLA HOWARD

Q: Gene Howard said you said you would do a resection for the possibility of extended life and that Bella’s tumour was called a DIPG, but there was a slim chance it wasn’t. He said you wanted to operate the very next day — the surgery would cost $100,000 and $50,000 had to be in your bank account that night. Immediately after surgery you said you had removed 95 per cent – which was “low grade and slow growing”.

Within days you received biopsy and had genetic marker for DIPG — but you “questioned the validity of biology results” and said resection their best option. Doctors interviewed say re-section of a DIPG was futile and harmful.

Mark has never heard of anyone trying to remove a “classic” DIPG.

The family said they appreciated the hope you gave them but questioned whether there was “any point” having the surgery and worried about the rush to operate and whether you gave them all the info they needed to provide proper, informed consent. How do you respond?

A: I honestly believed that there was a real chance that I could help Bella. The radiological characteristics were what is called aDIPG (atypical DIPG). 36% of aDIPG tumours are NOT DIPGs. Bella’s tumour has many of the characteristics of a focal lesion and therefore amenable to surgery and possibly even curable. Sadly Bella passed away but I tried my hardest to remove what was a very aggressive tumour. As for the money side, private hospitals demand money upfront before a patient is admitted and that is where the overnight money was spent. To try and help patients with costs, our previous practice was to give the patient a single bill and then we would pay all the costs out of the total sum. This turned out not to be practical and as such more recently we now just take the surgeon’s fee and let the patient pay the other bills individually. At no time do I coerce a patient into surgery. If the family felt there was an urgency it was their decision to go ahead the next day

It was a very sad end to Bella’s life. Both Bella and her parents were beautiful and kind people. Indeed, only last year, Gene contacted my office after a negative SMH media report expressing his full support and respect for me.

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE

Q: What do you say to claims you operate outside the Medicare system where there is no “checks and balances” and that in a private system you can operate as a “one man band”?

A: I do not operate as a one-man band but have a specialised neurosurgical team who work with me. I refer to specialists who I believe are the best in their field. I have a fellow who is a fully qualified neurosurgeon, often from one of the leading universities in the world, who is my major source of positive and negative feedback. Furthermore, to be accredited by the College of Surgeons, you must do a yearly audit of your log book and that applies whether you are in the public or private systems.

Q: What do you say to claims the private system has “allowed you to play God”?

A: Not worth answering

Q: What do you say to claims that in 2017 you let your accreditation lapse at POW public hospital?

A: I resigned from the public hospital in 2017 for no other reason than I was not given operating time. Theatre time is limited in the public hospital and I was sharing my time with a very good and young neurosurgeon who was busy and doing great work in the neurovascular field. As he became busier, my share of the operating time became less and less. Eventually, I had no time and hence resigned.

FEES

Q: The Howard family says of the $50,000 you demanded upfront you “pocketed $35,000” and charged an administration fee of $1000. Is that accurate?

A: I believe that the financial contract between a patient and his doctor is a private matter. Having said that I was always told by my mentors that I should charge what I believe I was worth. I am not sure how much the Howard’s were charged but my fees can fluctuate between $0 and $40,000 depending on the degree of difficulty of the procedure. That fee is then shared between me and my team, which includes the overseas fellow etc.

Q: 60 Minutes claims other doctors won’t go on the record with concerns about your “exorbitant fees, false hope and terrible outcomes”. What do you say to that?

A: Sadly. there is a lot of professional jealousy among surgeons, to the detriment of patients. I am not involved in the politics of the profession. However I understand many neurosurgeons, who say to patients that their tumours are inoperable and then they come to me and recover, would be annoyed with me. I will also say this … those critical colleagues might believe in the saying that “people in glass houses should not throw stones.”

KATHY LESLIE

Q: In 2018 Qld doctors told Kathy Leslie further treatment was too risky and likely to leave her husband, Joe, blind. He was given two years to live. They sought your opinion and you assured them you could remove for $35,000 and dismissed concerns it would leave him blind. They say the patient’s deal breaker was “going blind” and you said that’s not going to happen.

Did you give the patient those assurances?

His wife said there were serious complications and he was now blind and that would not have had the operation and resentful you “couldn’t care less” that you left him.

How do you respond?

A: I feel very bad for Joe’s condition post-surgery and wish him and his family well. However I did not tell them Joe would not go blind as I never give guarantees of success. The only promise I make to my patients is that I will try my best. I likely said that the probability of blindness was very low, and at the time I honestly felt that way.

— Cydonee Mardon is a former patient of Dr Charlie Teo’s