Paramedic reveals trauma behind most trusted profession

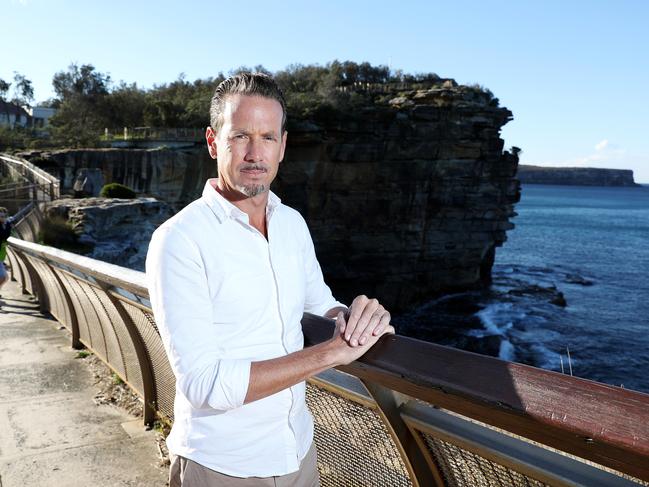

As a paramedic stationed for more than a decade at Bondi, Ben Gilmour has been sent too many times to The Gap but he never thought he’d have to deal with losing a close friend at this tragically beautiful landmark.

- Police blunder allowed paedophiles to roam free

- Existing drug gives new hope for kids with brain tumours

AS a newly recruited paramedic almost 25 years ago, Ben Gilmour appreciated the views from The Gap as much as the next person.

But after 12 years stationed at Bondi and too many shifts spent trying to coax down those literally and figuratively on the edge, The Gap now provides an entirely different outlook.

“For me and for a lot of paramedics, it’s a house of horrors,” he said. “It’s a strange kind of juxtaposition, this beauty and this deep sadness.”

As Mr Gilmore stood atop the cliffs in Sydney’s eastern suburbs this week, silently surveying the spectacular headland that juts dramatically into the Tasman Sea, an endless stream of tourists spill from busses, iPhones at the ready to capture one of the city’s natural beauties.

Most are unaware of the tragic secrets these cliffs hold, the wilting flowers and teddy bears tied to the fences intriguing some who point them out but spend little time deciphering their meaning.

MORE FROM DAVID MEDDOWS:

Kyle Sandilands finds big fan in rival breakfast host

The must-binge TV shows to see our winter

“When I look out across this view I see all the patients at different points, all the way along,” he said. “Looking down, I half expect to see a body on the rock shelf. It has become a trigger.

“I don’t think I have PTSD but they are scars and all paramedics have scars.”

When one of the tourists on the path screams to his wife at the top of the hill, Mr Gilmour swung around, wide-eyed.

“That really freaked me out,” he said.

At another stage he instinctively keeps an eye on a woman who is standing alone taking in the view.

“When I come here, I’m looking for signs. A car in the no stopping zone, a pair of shoes laid out, someone who looks despondent” he said.

Mr Gilmour walked to a spot on the winding path that hugs the coastline and stops. He said: “This is where John went.”

The countless hours spent battling to control the demons of strangers would be enough to turn anyone off this spot, but The Gap holds an even darker memory for Mr Gilmour.

It is the place where friend and colleague John Dixon, someone who sat beside him as they rushed to many of those calls, lost his own battle in January, 2008.

Mr Dixon’s death rocked Gilmour and his fellow paramedics, who knew he had been struggling after breaking up with his long-term boyfriend. But they never grasped the extent of his pain.

Mr Gilmour, who moved with his family to the state’s north coast in 2017, recounts that painful summer in his new book The Gap, a snapshot of the life of a paramedic during from 2007 to 2009. It’s a no-holds-barred account of the most trusted profession.

“I didn’t want to sanitise the job and make it into a hero thing where I’m just boasting about heroic things that I’ve done as a paramedic,” he said.

Called upon in the most trying of times, paramedics are a face of calm and often labelled “heroes” for the work they do. But Mr Gilmour isn’t a fan of that word.

“I have difficulty with the term hero,” he said. “I think it puts undue expectation on us and I certainly have always felt as if I could never meet that expectation.

“I could never live up to that expectation of that hero.”

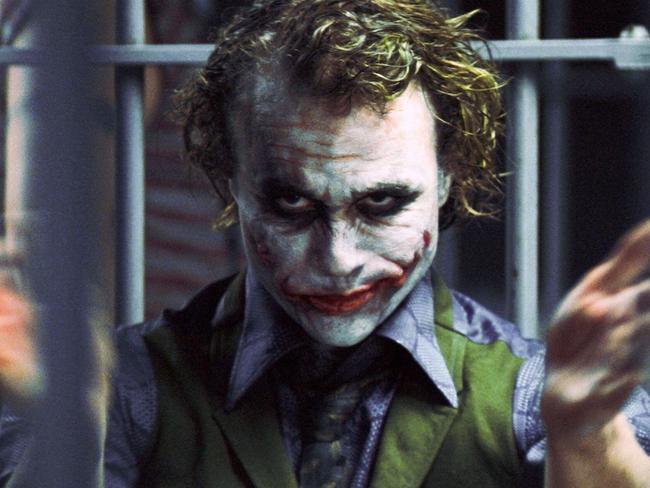

The Gap is also full of hilarious anecdotes of his time on the road, like when Mr Dixon went to his hero Heath Ledger’s Sydney home and pretended they had received an emergency call in the hopes of getting inside.

Much to his disappointment, it was Ledger’s assistant who answered the door before slamming it shut. It turns out John and Ledger died less than two weeks apart.

But the book also details the constant trauma faced by paramedics and the toll that takes on their mental health, something Mr Gilmour said has only really been dealt with properly in the past three to five years.

By shining a light on the struggles faced by those often seen as invincible, he hopes the book will provide some hope to those on the edge.

“I’m hopeful a book like this will help others in the community realise that if the most resilient heroes are feeling what they’re feeling, they’re more likely maybe to reach out for help,” he said.

* Lifeline 13 11 14

* Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467

* The Gap, Penguin Random House, $34.99