Mouse plague crisis: PETA cops backlash for telling farmers not to kill the rodents

Animal activists have been blasted for urging farmers not to kill mice in the name of ‘human supremacy’, as the rodent plague devastates rural areas.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A global animal rights organisation has bizarrely pleaded with farmers not to kill the mice plaguing regional Australia, arguing the rodents should not be denied their “right” to food because of the “dangerous notion of human supremacy”.

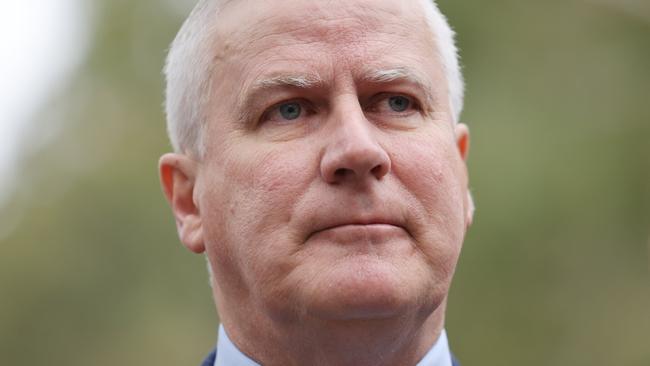

The comments from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) during the height of a devastating mouse plague has infuriated farmers and prompted the Deputy PM to slam the activists as “idiots who have never been outside the city”.

The ongoing rodent infestation across eastern Australia is on track to cause up to $100 million worth of damage and has already worsened a mental health crisis in the regions.

Some farmers have lost as much as $300,000 each in ruined crops as the mice chew through anything they can get their teeth in.

But PETA is urging rural residents to consider the welfare of the mice and avoid killing them with poison, instead suggesting the mice be gently caught and released unharmed.

“These bright, curious animals are just looking for food to survive,” PETA spokeswoman Aleesha Naxakis told NCA NewsWire.

“They shouldn’t be robbed of that right because of the dangerous notion of human supremacy.”

She said the government should take responsibility for the increase in mice and invest in humane methods of controlling the population.

“In the meantime, we urge farmers and residents to avoid poisoning these animals,” Ms Naxakis said.

“This cruel killing method not only subjects innocent mice to unbearably painful deaths, but also poses the risk of spreading bacteria in water when mouse carcasses appear in water tanks.

“Instead, humane traps allow small animals to be caught gently and released unharmed.”

The comments caused Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack to see red.

“The real rats in this whole plague are the people who come out with bloody stupid ideas like this,” he said.

“Their thinking around this is reprehensible, when you have farmers struggling.

“You have these people who have never left the city and wouldn’t know if their backside was on fire, then all of a sudden they’re telling farmers what to do?

“The only good mouse is a dead mouse.”

Gunnedah farmer Xavier Martin challenged PETA to try the catch-and-release model and see for themselves whether it would work.

“It’s not mice welfare we should be concerned about, we should be concerned about people,” Mr Martin said.

NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro agreed the PETA suggestion was “ridiculous” and an “insult” to people living in the regions.

“I would laugh if this wasn’t so serious,” Mr Barilaro said.

“The mice attack people while they are sleeping, they tear wiring apart and are wreaking havoc on the first good crop many farmers have had in years.

“I will not entertain PETA’s ridiculous concerns. Mice are pests. They are destroying crops and farming businesses, and the mental angst they are causing families is real.”

CSIRO mouse expert Steve Henry said he’d spoken to one farmer who had lost more than $300,000 to the rodents.

He said there was little people could do to stop the mice other than use poison to kill them.

The only poison registered for baiting large-scale cropping systems is zinc phosphide, while households must resort to over-the-counter mouse bait sold in supermarkets, according to Mr Henry.

He said research done by him and his colleagues on the strength of zinc phosphide had recently resulted in authorities allowing the use of stronger doses, which meant each mouse who ate a poisoned grain would die.

“I don’t know of any evidence to tell if an animal is suffering pain from that poison, but I would steer clear of the emotive stuff and stick with what we know,” Mr Henry said.

“We know mice are a terrible problem for communities. And we only have a few methods for controlling them.

“We need to use those methods as strategically as we can to reduce the problem that mice cause.”

The mouse plague has affected a growing area that stretches from southern Queensland, through central NSW to northern Victoria, and there has been an outbreak in South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula as well.

The rodents have exploded in numbers thanks to the same summer rains that came as a welcome relief for farmers who had suffered from the drought.

The pests can become pregnant when they’re just six weeks old, and will have a litter of up to 10 newborns every 20 days.

That means the population can rapidly get out of control, as many regional residents have experienced in recent months.

John Southon, the principal of Trundle Central School, a rural NSW school that has been overrun by mice, said PETA’s comments were demeaning to people in the regions.

“I think it’s just another absolutely ridiculous concept from people who have never lived through a mouse plague and can’t see the damage that they do,” he said.

Clinical psychologist Gene Hodgins said that people’s mental health was a real concern because the mouse plague was merely the latest in a string of catastrophes they’ve had to battle, including the drought, fires, floods and COVID-19.

“The chronic stress leads to physical issues – fatigue and lowered immune system – and mental issues,” said Mr Hodgins, who works for Charles Sturt University.

“The mouse plague leads to a sense of helplessness, it’s pervasive and it impacts every part of people’s lives, both at work and at home. There’s no respite,” he said.

There are other health impacts as well. NSW Health has reported a sharp spike in cases of the mouse-related disease leptospirosis over the past few months.

The total number of cases so far this year, 39, is already higher than the past two years combined.

The Hunter and New England area has borne the brunt of the leptospirosis spread, with a total of 21 cases so far this year of the disease that causes flu-like symptoms and can lead to death in severe cases.

Severe mouse plagues tend to affect Australia about once every decade.

Although it has not been possible so far to quantify the damage done by the current one, a 1993 outbreak that was on a similar scale ended up causing an estimated $96 million in damage, according to the CSIRO.

A recent survey by NSW Farmers showed nearly all of the around 1300 respondents had baited for mouse control since the spring.

About 10 per cent had spent more than $50,000 on bait, with 15 respondents saying it cost them more than $150,000 each.

Additionally, 48 people told the survey they had lost more than $250,000 in ruined grain, fodder and crops due to the mice.

More Coverage

Originally published as Mouse plague crisis: PETA cops backlash for telling farmers not to kill the rodents