Dossier reveals truth about shock deaths at Sydney’s biggest mental health hospital

TWO patients took their own lives and a third, carelessly labelled “low risk” by staff, tried to hang herself with a household item that should have been banned, in the space of just three days at Cumberland Hospital.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TWO patients took their own lives and a third, carelessly labelled “low risk” by staff, tried to hang herself with a household item that should have been banned, in the space of just three days at Cumberland Hospital.

Root Cause Analysis reports by NSW Health obtained by The Daily Telegraph can today reveal how a dire lack of beds and staff at the state’s biggest public mental health facility is seeing people discharged far too early.

At times they’re discharged without “comprehensive” plans or any “engagement with the family”. The documents — Root Cause Analysis reports of the three incidents by the Western

Sydney Local Health District — also raise concerns staff may have doctored patient notes to make it look like they were doing more checks than they actually were.

The cases shed new light on the perilous state of the ageing 260-bed facility, which was first opened in 1849 and is now part of the major Westmead health precinct. The government recently committed to closing the hospital, but no date has been has been set for when patients would be moved.

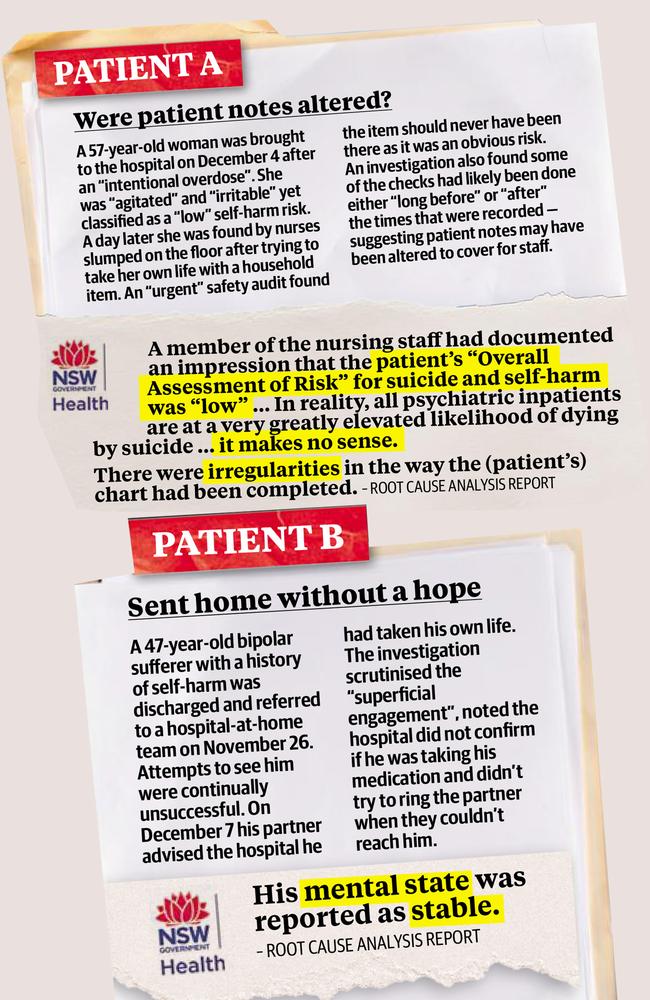

One report shows how on December 6 a 57-year-old woman admitted to Cumberland was left unsupervised and found by nurses “slumped on the floor unresponsive” after trying to end her life using a basic household item. The review found the item should never have been there and recommended its “removal ... as a matter of urgency”.

Despite intentionally poisoning herself just hours earlier and being described as “agitated, irritable, hostile and verbally aggressive” she was classified as a “low” suicide risk.

“In reality, all psychiatric inpatients are at a very greatly elevated likelihood of dying by suicide,” the report by Western Sydney Local Health says.

EDITORIAL: STILL MUCH TO DO IN MENTAL HEALTH

The woman lived, but the internal investigation was so damning it raised concerns that staff may have doctored time sheets. “Some of the checks corresponding to times before the incident may have been made either long before the incident or after the incident,” it said.

The following day there was another incident which resulted in the death of a 47-year-old man diagnosed with bipolar and who had a “significant” history of self-harm.

He was discharged and referred to the hospital’s external response team on November 26 because “his mental state was reported as stable and he denied any suicidal ideation”.

But staff were unable to contact him after his release.

On December 13 his partner rang the hospital to tell them he had taken his own life. The third incident involved the death of a 33-year-old indigenous man diagnosed with schizophrenia. Despite a two-week involuntary order on November 22, he was released after six days.

On December 3, a day after appearing at another hospital hearing voices telling him to kill himself, he returned to Cumberland but was allowed to leave with medication.

Despite finding he did not have medication on December 6, mental health staff left the man. He committed suicide two days later.

A report into the death notes “discharge planning did not include a comprehensive crisis management plan” or “evidence of interaction and engagement with the family”.

And the report warns “the Medical Officer did not consult or contact the on-call Psychiatric Consultant in regard to decision-making and reasons for discharge”.

The Telegraph can also reveal Cumberland has been forced to close a ward because of a major fire — adding pressure to bed shortages.

Sue Collins, a nursing manager who left earlier this year, described the facilities as “so bad that they are dangerous and unfit for patients”.

“There has been the loss of over 50 nursing positions in the hospital and community over the past few years,” Ms Collins.

“Wards work constantly short.”

Internal memos confirm Cumberland’s only high-dependency unit, Yaralla, was shut between December and March. Another ward, Paringa, has been operating at a significantly reduced capacity due to a fire.

A third, Rupertswood with 16 beds, is permanently closed.

Beth Kotze, the director of mental health services, said “community care is the preferred model of care for all mental health patients”.

“However, there will always be patients that cannot be appropriately or safely managed in a community setting, making npatient care the only practical option”.

Mental Health Minister Tanya Davies said her “heart goes out to the family and friends of the two men who lost their lives, and the woman involved in a tragic incident”.

“I have been assured … thorough investigations of all three incidents took place and have been advised all recommendations were actioned,” she said.

“The government is committed to changing the culture, leadership and environments in which our loved ones receive care.”

BURNING QUESTIONS REMAIN AFTER FIRE

CUMBERLAND Hospital was forced to shut an acute mental health ward after an unsupervised patient set it on fire — leaving a trail of destruction.

Nurses who spoke on condition of anonymity said there was no functional sprinkler system in the Paringa ward of the hospital before the October 13 fire, which forced the evacuation of 30 patients.

Images of the devastating impact of the fire reveal burnt-out bedrooms and bathrooms.

The ward closure has only added to overcrowding issues already plaguing the hospital.

“The unit is currently being assessed to determine the full extent of the damage. Until the unit is deemed safe, patients will be reallocated to other suitable units across the service,” a memo to all mental health staff sent on October 13 reads.