Still much to do in mental health

ENGLAND’S very first hospital specialising in treatment of mental illness was established during the mid-13th century as a clinic for the poor.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ENGLAND’S very first hospital specialising in treatment of mental illness was established during the mid-13th century as a clinic for the poor.

By the early 15th century, the majority of patients at London’s Bethlehem Hospital were classified — using the terminology of the day — as lunatics.

It may seem farsighted that mental illness was considered a matter of major public concern so many centuries ago. For the era, this is undoubtedly the case.

But the treatment methods practised within Bethlehem reflected a dark and terrifying time. The website Historic England records the hospital’s primitive means of dealing with its many troubled inhabitants:

“Those who became patients were usually the poor and marginalised, sometimes believed to be dangerous, who lacked friends or family to support them. The hospital regime was a mixture of punishment and religious devotion — chains, manacles, locks and stocks appear in the hospital inventory from this time. The shock of corporal punishment was believed to cure some conditions, while isolation was thought to help a person ‘come to their senses’.

“It was a religious duty to care for and feel compassionate for people afflicted by madness.”

Centuries later, treatment of the mentally ill has advanced. Yet we still find among them many who are poor, marginalised, and who lack support. We also find, as The Daily Telegraph reports, chilling lapses that expose the mentally ill to shocking and deadly dangers.

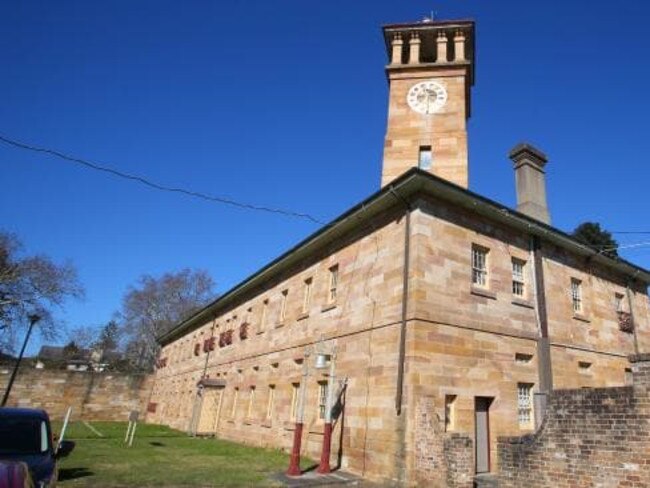

Confidential documents reveal that three patients at Cumberland Hospital, Sydney’s largest mental health facility, last year attempted to kill themselves within days of each other. Dreadfully, two succeeded.

The surviving patient, a 57-year-old woman admitted to the hospital after trying to poison herself hours earlier, and whose condition was described as “agitated, irritable, hostile and verbally aggressive”, had been left unattended following her assessment as a “low” suicide risk.

She was subsequently found “slumped on the floor unresponsive” after wrapping a pay phone cord around her neck.

A former nursing manager at the hospital, Sue Collins, claims Cumberland’s facilities are “so bad that they are dangerous and unfit for patients”. Staff shortages are acute, which reduces opportunities for wellbeing checks on discharged patients.

Society has come a long way since the dark days of Bethlehem yet clearly there is still a long way to go.

ELECTION WILL BE A CONTEST

DURING the early months of 2016, the short-term political future for NSW seemed remarkably clear.

Premier Mike Baird enjoyed enormous popularity. His Coalition government, re-elected in 2015, enjoyed a substantial majority over Labor. A sequence of ill-advised decisions then saw Baird’s approval decline by 46 points — leading eventually to the premier’s resignation last year.

Baird’s former deputy Troy Grant has now also announced his departure from politics as the coming election suddenly looms as something of a contest. It’s all to play for in 2019.

FIRING BLIND ON ENERGY CRISIS

BILL Shorten came out swinging yesterday, claiming the energy debate had given way to “placating the knuckle-draggers of the cave-dwelling right of the Liberal Party, promising mirage coal-fired power stations which cost billions of dollars”.

According to the Labor leader, seeking a reliable and inexpensive means of providing power is evidence of “knuckle-dragging”. Shorten’s coal condemnation is driven by his desire to lure inner-city former Labor voters back from the Greens. Yet more intriguing was Shorten’s scathing words were prompted by a crucial element of the power debate — the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s energy industry report.

You would imagine anyone serious about energy issues — or anyone serious about reducing the outrageous cost of energy for average Australians — might have bothered to read the ACCC report before offering an opinion. As the Labor leader himself admitted, however, he hadn’t read it at all.