Cruel lessons of Bowraville families’ long fight for justice

In 34 years as a cop, I’ve learned how racist Australia can be – and in the case of three murdered children in Bowraville, the cold fact is these families were treated differently because they were Aboriginal. It seems little has changed, writes Gary Jubelin.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- The day I found myself on Black Lives Matter march

- Gary Jubelin: how policing left one cop black and blue

In August 2016 a sombre crowd of mainly Aboriginal people gathered in a children’s playground opposite a small cluster of houses in an area known as ‘The Mission’ on the outskirts of Bowraville. There was an air of anticipation when then NSW Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione walked nervously towards the microphone. This is a moment the community had been waiting decades for.

Silence fell over the crowd. The Commissioner spoke with purpose and compassion: “I want to publicly acknowledge that the NSW Police Force could have done more for your families when these crimes first occurred and how this added to your pain, as a grieving community.”

It was a victory in part for this small marginalised indigenous community on the mid north coast of NSW. They had finally got their apology.

As a homicide detective, one of the saddest things I encountered was when a child was murdered. It is devastating to families and communities. Imagine now if three children were murdered one after the other over a five-month period in a small country town, what impact that would have.

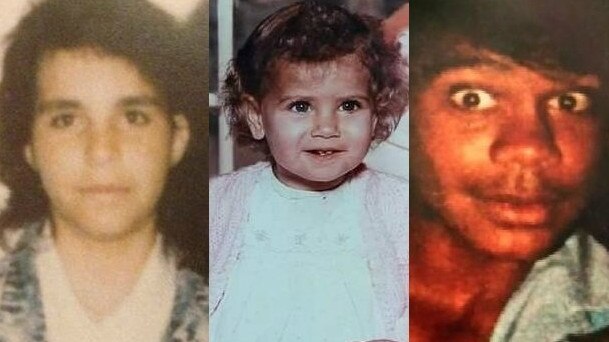

That’s what the families of three children: Colleen Walker, Evelyn Greenup and Clinton Speedy-Duroux faced in 1990 and 1991. Colleen, 16, disappeared on September 13, 1990. Her remains have never been found. Her four-year-old cousin Evelyn vanished on October 4, 1990 and her body was found nearly six months later. She had suffered severe head wounds. Clinton, 16, was reported missing on February 1, 1991 and his body was found, also with head wounds, just dumped in the bush a fortnight later.

People didn’t care. These were Aboriginal kids. And worse – the police response was substandard. When the family tried to report Evelyn – a preschooler – missing on the day of her disappearance, they were told to come back another time.

Police suggested Evelyn may have “gone walkabout”, even as her family insisted, she was a clingy child who’d never wandered even a short distance away. The families desperately wanted police to help, but repeatedly were subjected to prejudice and indifference. Even though the evidence suggested this could be the work of a serial killer, the case was left to a detective sergeant with no homicide experience.

At this stage no person has been convicted of these brutal crimes. The fact the families are continuing to fight for justice for their murdered children is truly remarkable. It’s also a testament to how loved the children were. The word ‘fight’ is not overstating what the families have done. They learnt a long time ago unless they agitate and push for justice, these murders will be completely forgotten.

I started investigating the Bowraville murders in 1996, when Homicide was given the case by then-Commissioner Peter Ryan and Strike Force Ancud was formed.

Detective Senior Constable Jason Evers and I, along with several other officers, spent a decade trying to find new evidence about each of the three murders, and to link the cases together. We spent years gaining the trust of the community.

Through that trust new evidence was uncovered including critical witness accounts which had never been shared with police before. It has been a sad and incredibly frustrating journey.

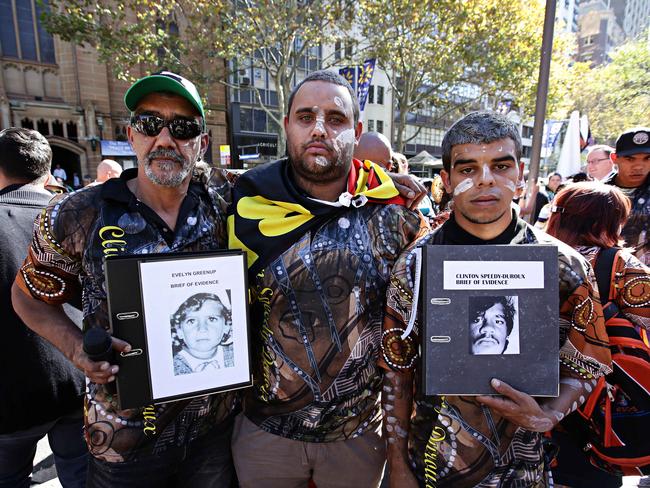

There have been failed criminal trials, numerous public rallies, campaigns to have legislative changes, Parliamentary inquiries and more protests. It’s now 30 years since the children were murdered and the families’ efforts for justice has now been passed on to the next generation. Young adults who weren’t born when the Bowraville children were murdered are continuing the campaign their parents, aunties and uncles started.

On the surface the NSW Police seemed to be true to their Commissioner’s word. They followed up the recommendations of the NSW Parliamentary Inquiry into the Bowraville matters. This included producing a training film made to educate NSW Police about the lessons learnt from Bowraville.

On the 24 July 2019, Assistant Commissioner Stuart Smith gave evidence at NSW state parliament before a parliamentary committee. When referring to lessons learnt from Bowraville, he said: “The outcomes from that are now taught to every investigator in NSW. Every police officer coming into the force gets cultural awareness training so we can understand how best to collect that evidence.”

Credit should be given where it’s due. The NSW Police have learnt lessons from Bowraville, but now is not the time to sit back and rest. When a community is traumatised as much as Bowraville, they are naturally sceptical and need constant reassurance.

I know the community and have shared their pain. I felt like I was letting them down when I resigned from the NSW Police on the 12 July 2019. I rang the families and told them I was retiring and there were tears and anger in equal portions from both the families and myself. I was gutted but determined to do what I could for the families.

Prior to resigning I sent an email to senior police requesting that I be allowed to debrief with the Bowraville families and assure them their fight for justice will not be forgotten with my retirement. It didn’t seem a lot to ask, but my request was ignored.

Inexplicably, the other two NSW Police employees who have detailed understanding of the investigation, having worked with the families for the past 10 years, have not been consulted with regarding the status of the investigation, nor asked to liaise with the families.

As of going to press late last night, the families had not had a phone call or visit from NSW Police since my retirement. Nor have they been told who is leading the investigation.

NSW parliament is considering possible legislative changes when parliament resumes which could have a significant impact on the Bowraville investigation, but no one from the NSW Police has bothered updating the families.

If that sounds difficult to comprehend given the history of this matter, sadly it gets worse.

In September 2019 the families conducted a peaceful protest march in Sydney’s CBD. One outcome they were seeking was for the NSW Police to let them know who was running the investigation after my retirement.

They got no response.

In November 2019 a heartfelt letter signed off by all three families was sent to the Police Commissioner asking among other things who was now running the investigation. They received a written response back saying the matter would be referred to the “relevant commands”. Two weeks ago, a signed letter by Commissioner Fuller addressing some of the issues raised was received by the families.

After the Sunday Telegraph made inquiries to police on Saturday, homicide squad commander Danny Doherty said the case had been referred to the Unsolved Homicide Unit.

“The case will undergo a formal review under the Unsolved Homicide Unit’s review framework, which is standard process once all current lines of inquiry have been exhausted,” he said. “Detectives contacted family members in November 2019 to advise them of this development.”

Detective Inspector Doherty said a $250,000 reward was still available for information leading to a conviction.

I was proud to be NSW Police Officer and I want to be a positive advocate for them, but I stand with the Bowraville families on this one. It is disgraceful the NSW Police are treating the families in such a manner. They have suffered enough.

Communication and compassion is not a lot to ask for.