’You kill black babies’: a white protester’s slur against Aboriginal cop

Growing up in Redfern and witnessing police racism first-hand made Jarin Baigent determined to join the force and change things for the better. GARY JUBELIN reports

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE birthday party at Penrith Leagues Club was winding up, and Jarin Baigent and her brother began making their way home. A fight broke out that did not involve them, but when they saw a woman being assaulted, Baigent’s brother ran towards the brawl to try and help.

Suddenly police were on the scene and her brother was being handcuffed.

“He was just trying to stop the fight,” Baigent told the officers. They ignored her.

“I’m a cop,” Baigent told them.

And so she was — but she is also Aboriginal, and that meant, for the hundredth time, Baigent was forced to choose between black and blue.

She chose black, continuing to speak up for her brother. That resulted in a formal interview and caution for ‘hindering an investigation’, and a lingering feeling she was caught between two worlds.

It was one of many moments in Jarin Baigent’s 13-year police career when she felt torn between her affiliation to her family, her culture, her community – and the police force she had grown up to dream of joining.

“I’d invited my brother to the party. I thought it would be a good idea for him to attend a police function, to see cops are normal people. Since that day his distrust and hatred of cops increased exponentially,” Baigent says now. “I can’t blame him on that occasion.”

BLACK AND BLUE

Baigent is better placed than most to understand the complexities of the relationship between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the police. She was the first Aboriginal police recruit who’d grown up in and around The Block in Redfern.

Given the tense history between residents of the Block and the local police, that in itself was remarkable.

Redfern was, and still is, a place that draws Aboriginal Australians from around the country. It’s also long been the epicentre of police-community conflict. Even at a young age, Baigent was very aware her family did not like the police and the feeling was mutual.

Perhaps surprisingly that very hostility triggered Baigent’s desire to become a cop.

When she was about seven years old, the family home was burgled for the 10th time. Police turned up for a cursory look around. “Even at that age I could tell they didn’t like us and weren’t even interested,” Baigent says now.

“It was like they wanted to get out of there as soon as possible.

“I was a young Aboriginal girl, raised with a distrust of the police, but I wanted to make a difference. I was going to join the police so that others didn’t have to experience what I felt when the police ignored my family.”

Baigent, a fighter her whole life, does not shy away from a challenge. Her brother is not the only person in her family who had unpleasant encounters with police.

As a kid, she moved between her separated parents and spent some time living near Blacktown.

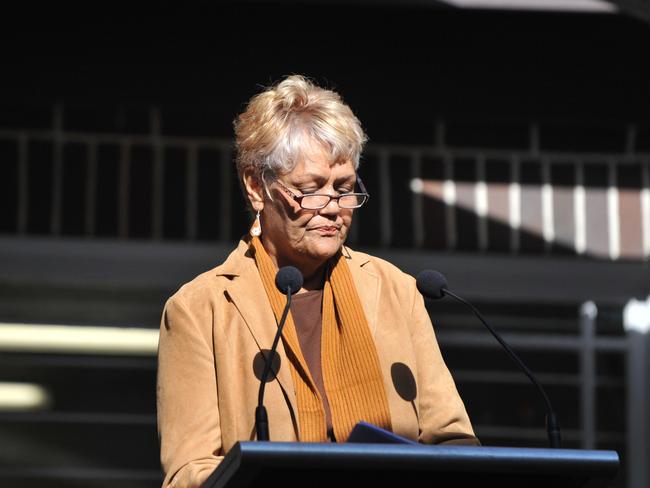

At the family’s centre was Millie Ingram, Baigent’s grandmother and a highly respected elder in the local community and beyond. Mrs Ingram, who’s spent a lifetime standing proud for her people’s rights, delivered the Welcome to Country at the 2014 memorial service for former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

“When Jarin told me she wanted to join the Police, I was determined to talk her out of it,” Mrs Ingram says over coffee in Redfern. “I knew how hard the journey would be for her in both worlds. But she was stubborn and I changed my view and supported her two hundred per cent.”

Jarin Baigent didn’t take the easy path through policing. She spent five years as a general duties officer at Mount Druitt, two years as a surveillance officer and her final five years working the beat where she grew up in Redfern.

She was also seconded to the Northern Territory to work as an engagement officer on the Royal Commission into Detention and Protection of Children. Much of her work was developing recommendations for working with NT Police. “I felt the pressure as an Aboriginal woman to make sure I did a good job for the children and their families,” she says now.

Policing Redfern was rewarding but also deeply confronting, she says. She’s unashamed to say she saw herself as an Aboriginal woman first, and a police officer second. But there’s a hint of frustration — not bitterness or anger — that police didn’t fully use her unique understanding of her community’s needs and sensitivities.

REDFERN ERUPTS

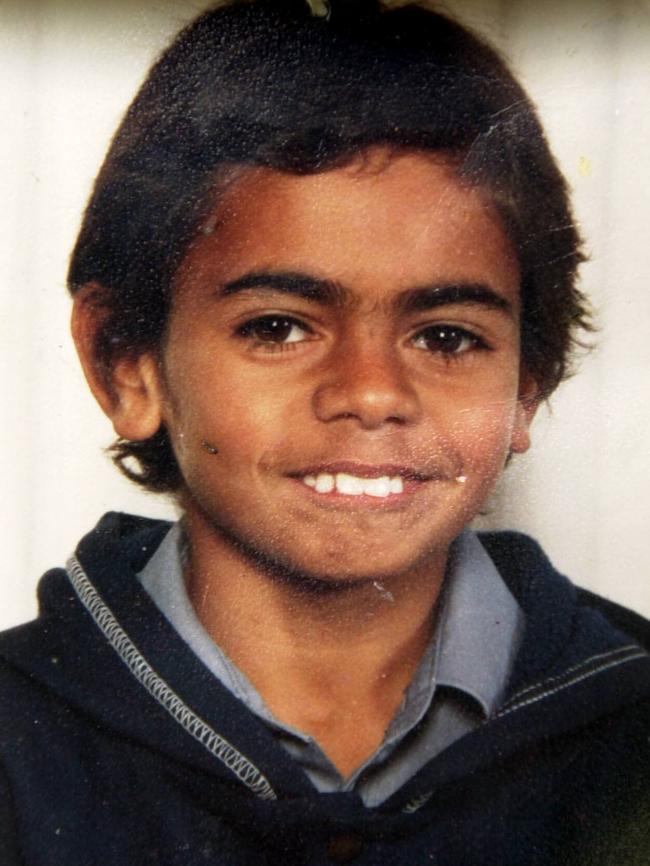

In 2004 Redfern exploded with anger and violence following the death of TJ Hickey, a 17-year-old Aboriginal boy who was being followed by police while riding his bike. He crashed into a gutter — after what his family claims was a collision with the police vehicle — and was flung into the air and impaled on a metal fence, sustaining fatal injuries.

The death, and public outrage at what was perceived as a police pursuit, triggered the worst police-community violence in Sydney’s recent history, with rocks, bricks and molotov cocktails thrown at police, the train station set on fire and dozens of people injured.

Baigent wasn’t there that night, but on one of the anniversaries of TJ’s death as the community gathered for a protest, she was assigned to help hold a police line against a group of angry, mostly non-Aboriginal demonstrators.

“Murderers!” yelled a white middle-aged lady at Baigent, who was dressed in her police uniform. “You kill black babies! Murderers!”

Baigent was standing just metres from the Aboriginal-run kindergarten she’d attended as a child. “On this occasion I could actually see prejudice through my police eyes, that was directed at police and not Aboriginal people. It was a different perspective,” she says.

When asked whether she saw racism in the police, Jarin pauses.

“Yes. The problem is racism is so deeply ingrained that people don’t even know they’re doing it,” she says. “Added to that is just how uncomfortable Australia is as a whole addressing racism.”

She’s concerned about the low retention rate of Aboriginal police officers and thinks NSW Police must do more to retain the Aboriginal cops who are prepared to live in both worlds.

“There needs to be clear pathways of Aboriginal leadership, especially for sworn officers. We are not just a number. We bring a set of very unique lifelong skills and social capital that directly benefit any organisation we work for. That also means more responsibility.”

Life has purpose for Baigent outside the police. “I am content with the direction my life is heading,” she says.

Today, she’s running her own business, Jarin Street, making yoga mats with indigenous artworks whose creators earn royalties, creating sustainable income pathways for the community.

“I am sad about leaving the police but it was also a difficult time,” she says. “I was seen to be a role model and in some aspects a leader, in my own community, but within the police I was just a number. The value of my Aboriginality as an expertise was not appreciated. It is difficult for Aboriginal police officers walking with one foot in each world.”

Baigent’s also nurturing a dream of writing a book about the stories of Aboriginal police officers. “I want to tell these stories before they are lost,” she says. “I just need to find a publisher that may be interested in a fascinating part of our history.”

It is truly a shame, I think, that NSW Police has lost such an impressive person.