Circular Quay: Murky past of Sydney’s tourist hub

Once a muddy, mosquito-ridden swamp where convicts laboured, and custom’s officials ruled with an iron fist, before Circular Quay became a glistening tourist hub, it was a rough and tumble place.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Central Station: Sydney’s busiest station has a dark secret

- Sydney’s Garden Palace, the building you’ve never heard of

- Brawls, booze and murder: Sydney pubs with a sordid tale to tell

BEFORE thousands of tourists and commuters tramped its paved promenade, Circular Quay was little more than swampy mudflats plagued by mosquitoes.

But with its deep anchorage and beautiful vista, it was always destined to be more.

From the moment Captain Arthur Phillip first raised the Union Flag on January 26, 1788, the site — then known as Sydney Cove — would prove vital not only to the survival of the First Fleet and early British settlers, but to the birth of the country’s wealth.

It would quickly become a hub of trade and export and home to some of Australia’s oldest buildings, some which still stand today.

Sydney Cove was also one of the first — and last — locations to use convict labour. City historian Lisa Murray says it was not an uncommon sight to see sailors, business people, and visitors “schlepping along in the mud” as sandstone tumbled down the rocks into the harbour.

So in 1836 a plan was devised to reclaim the mudflats and install a seawall around the cove. The plan was so unpopular, it took five years to get both public and government approval.

Construction of Circular Quay — or Semi Circular Quay as it was officially known — began in 1841 and involved filling in the mouth of the Tank Stream, which flowed into Sydney Cove.

Sandstone was quarried from Cockatoo Island with one section of the wall around Farm Cove taking 30 years to complete.

Ms Murray says the remnants of that era are literally under foot.

“If you were to walk from the ferry wharf towards the Opera House and look down at the pavement you will see tiny discs which map out where the foreshore was over periods of time,” Ms Murray says.

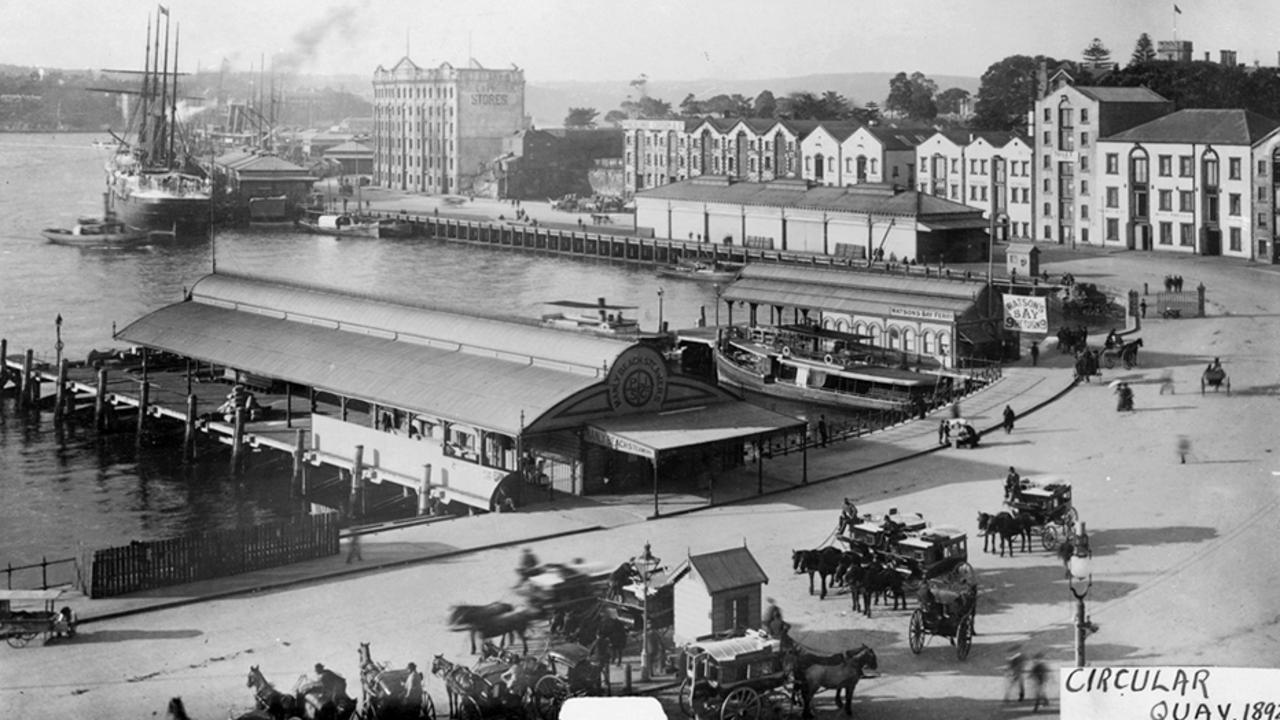

Sydney Cove was the main shipping and trade route in and out of harbour with the surrounding area giving birth of warehouses and trading empires.

Goods imported included tea, ginger, and alcohol from China and India, and later crockery and linen.

And as Australia’s wool industry flourished, so too did its trade.

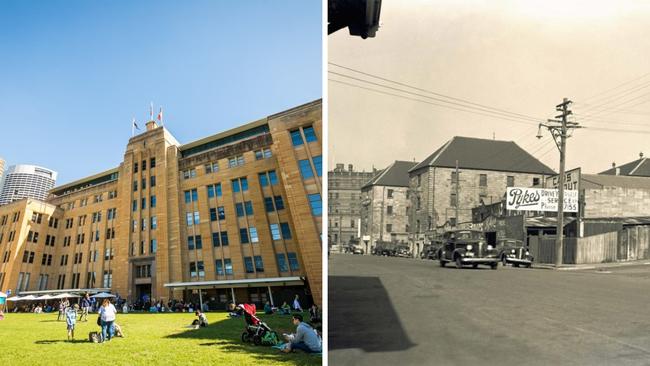

Ms Murray says Customs House, opened in 1845, would become the “linchpin building” in all of the Quay as merchants had to register their goods and pay their taxes, and was the first port of call for those entering the colony.

Soon warehouses, wool stores, bonds shop and pubs would spring up around Customs House.

An article in The Daily Telegraph published on June 22, 1887 described the atmosphere around Circular Quay, observing the “Quay presented a busy appearance” as a steamboat made its way to the wharf and fireworks illuminated the night sky.

“It was a pretty sight looking around the foreshore … either side of the Quay brilliantly illuminated. The gleam of many colours reflected on the water … the hum of thousands of voices, the tread of many feel, the roil of omnibus and cab traffic, the cries of children …”

And while Customs House kept an official watch over what entered the colony, it also played a vital role in ensuring “undesirable” good did not enter. These included prohibited items such as opium, electric goods for therapeutic purposes, astrological charts, and at the turn of the century — contraceptive devices.

It was also the nation’s border control after the introduction of the controversial White Australia policy in 1901 — setting strict tests in any European language they chose — which discriminated against Chinese and non-Europeans hoping to immigrate.

Customs officers would also search ships coming in to port for stowaways and conducted nightly patrols of the wharves catching those who tried to sneak ashore.

But there was one undesirable Customs struggled to keep from coming ashore — and one that would bring death and fear through the colony.

Rats. Specifically flea-infested rats carrying the bubonic plague.

The death of Captain Thomas Dudley in February 1900 spread fear through the slums and housing estates surrounding the wharves as authorities struggled to contain the outbreak. The sight of hundreds of dead rats in the streets was not an uncommon.

The Sydney Harbour Trust was formed in 1900 giving it control over the Port of Sydney. One of their first acts — and in response to the plague — was to order the knock down of all the wharves and the demolishment of slums and buildings in surrounding areas.

They would later rebuild the wharves but by then the larger ships started docking at Darling Harbour and later as containers boomed Port Botany.

Customs would later come under federal rule and as smaller ships gave way to shipping containers and airfreight, Customs House no longer needed a waterfront location. After 145 years, Customs vacated the premises in 1990 and four years later the building’s ownership was transferred to the City of Sydney Council.

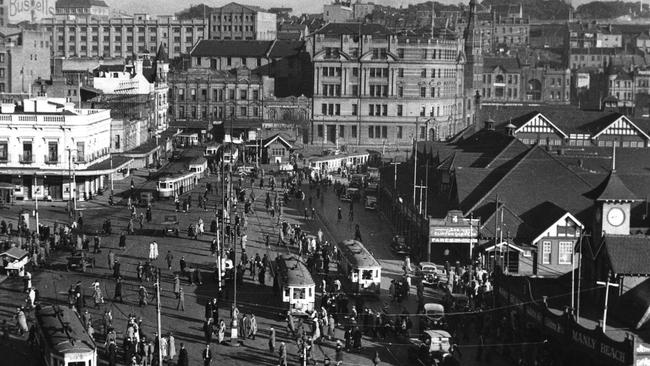

Circular Quay was no longer the main port for shipping but would soon emerge — and remain today — the main commuter ferry hub. And later a key tram and train interchange.