Bubonic plague Sydney: How a city survived the black death in 1900

IN 1900, a Sydney wharfie who had been removing rats from his toilet died of the bubonic plague. A wave of public panic followed. The dreaded outbreak had begun.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT BEGAN with a ferocious headache, nausea and dizziness on a hot afternoon on January 19, 1900.

Delivery driver Arthur Payne, who worked for the Central Wharf Company, found himself desperately ill as he made his way through the crowded, unsealed streets of Sydney.

Arriving home at 10 Ferry Lane, Millers Point, just before dark, the 30-year-old downed a dose of castor oil, vomited profusely, and passed out in bed.

The next day, he was officially diagnosed with bubonic plague.

Payne, who was quickly quarantined along with four family members, survived his brush with the black death but others were not so lucky

About a month later, Captain Thomas Dudley, who also worked at the wharves, began showing symptoms.

The sailmaker, who had been staying in Sussex St near east Darling Harbour, had noted scores of dead rats in his neighbourhood. He had been pulling dead vermin from his toilet before falling ill.

Dudley became the city’s first plague fatality and his death set off a wave of panic.

Authorities, who had been anticipating an outbreak after the disease raced through Hong Kong and New Caledonia, put the medical garrison on alert at North Head Quarantine station.

For the next eight months, Sydney would be a city under siege.

PANIC GRIPS SYDNEY

Far from being eradicated, the bubonic plague continues to exist around the world with about 3000 human cases reported annually.

In the US, there have been 12 deaths since April this year.

Australia has not been immune, with 12 major plague outbreaks between 1900 and 1925 as ships imported waves of the flea-carried bacteria known as Yersinia pestis.

The outbreak in Sydney in 1900 prompted a wave of public panic as the plague, which arrived on fleas brought ashore by ships’ rats, began to thrive during the warm wet autumn.

Most virulent in the harbourside slums around Darling Harbour, those who could afford to fled the city and real estate agents were inundated with calls for suburban properties.

Fear bred hostility and the newspapers were full of lurid stories about the “Black Death”. People were marched off in the middle of the night to be quarantined and the names of those infected or deceased were published daily.

Xenophobic attacks also began appearing in the press, with Italian and Chinese migrants among those blamed for importing the plague through poor hygiene.

Squadrons of ratcatchers were formed and in the next few months, tens of thousands of vermin were killed and burned in a special rat incinerator with some councils paying six pence a head, making the pestilence very profitable.

Within a few months of Captain Dudley’s death, the plague had spread along transport routes across the city and quarantine areas were established from Millers Point west to Chippendale and Glebe, as far east as Paddington and Manly in the north.

Knowing the ravenous potential of the disease, authorities made North Head’s quarantine station the city’s first line of defence, a fortress designed to delay and destroy the “deadly foes threatening to storm the great metropolis.”

The infected were quarantined, the dead interred with quick lime to hurry their decomposition and by the year’s end, more than 1700 people had been sent to the station.

Many would never leave its lonely burial ground.

URBAN RENEWAL

The plague had far-reaching effects for Sydney, then a burgeoning city with a population nearing half a million.

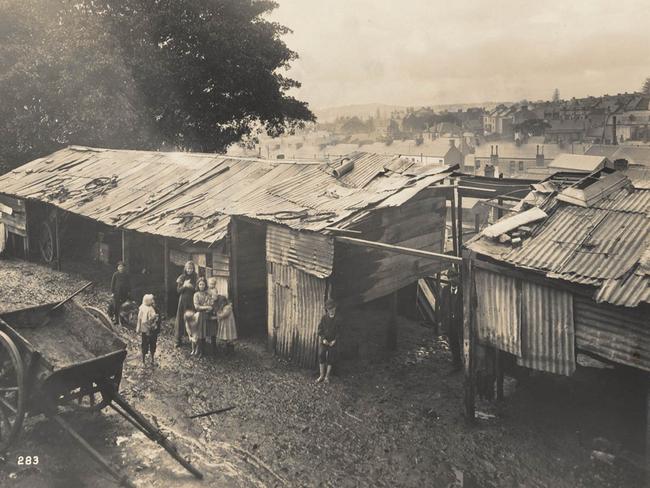

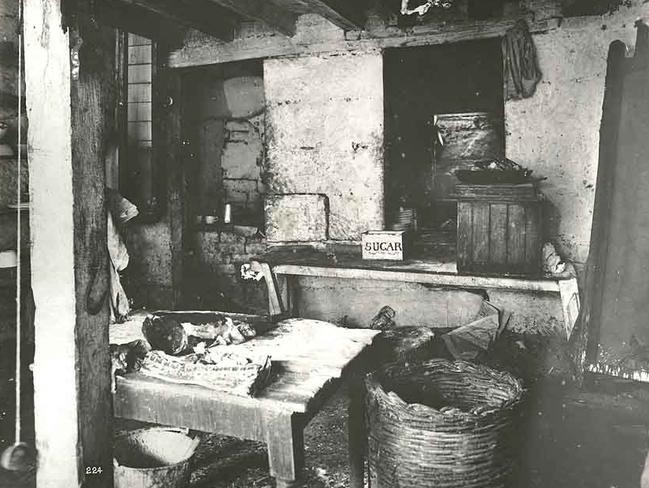

It paved the way for significant urban renewal of waterfront precincts such as The Rocks and Millers Point, where a century of unregulated building had created shanty towns ripe for disease.

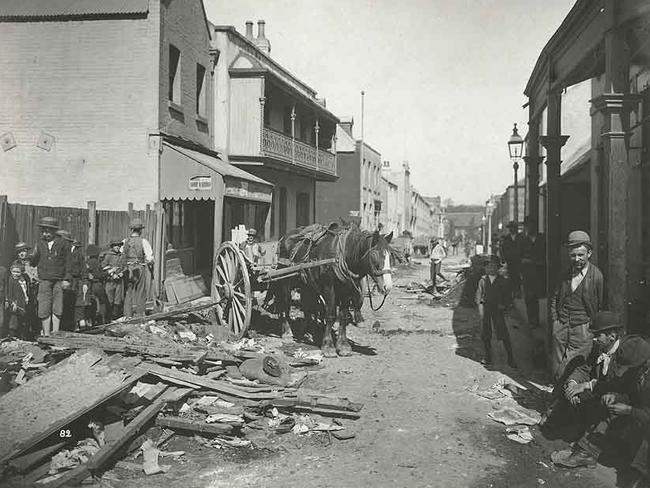

Between March and July 1900, The Rocks and waterfront areas were barricaded off and residents armed with lime, carbolic acid and sulfuric acid, enlisted to cleanse, disinfect and even burn and demolish their own houses in infected areas.

Government inspectors photographed buildings before and after and the State Library archive reveals just how squalid the conditions were for the poor in the city at the time

By the end of August 1900, the outbreak had concluded. A total of 303 cases had been reported and 103 deaths occurred, a number significantly low when compared to mortality rates from other infectious diseases of the time.

The reshaping of the city continued, however, as the disease provided a convenient “public health” excuse for resumption of private property.

The NSW Government took back ownership of virtually the entire headland from Circular Quay to Darling Harbour and demolished hundreds of slum houses and businesses in what are now prime real estate precincts such as George St, Sussex St, Kent St and Martin Place.

There was little attempt to define a slum area and there was no recognition of the rights of tenants as resumptions took out a house here, a street there and great swathes of properties in some suburbs to improve crooked roads and thoroughfares.

Green Bans in the 1970s on the redevelopment of The Rocks helped preserve the remaining historic area of The Rocks, which is now a major tourism precinct.