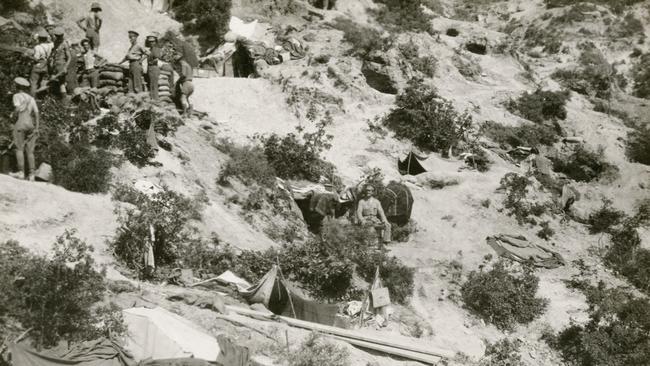

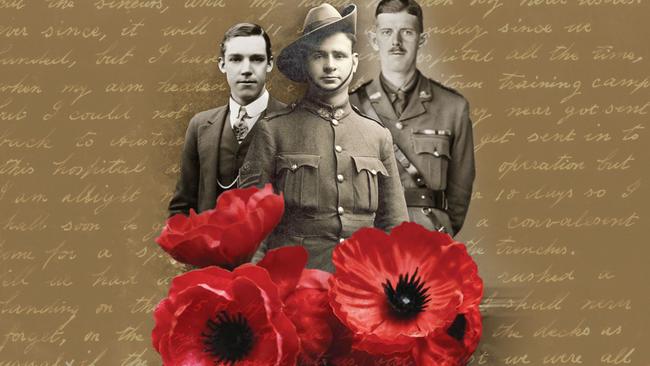

After more than 100 years, Australians are finally hearing the Anzacs of Gallipoli in their very own words.

Heartbreaking frontline accounts, written across the ranks from privates to brigadiers, were sent home to family members, detailing the heroism and the horrors of the campaign that made Australia’s name.

But until now, most have never been seen.

Written in ink on fragile paper, jotted down by the men as the madness of war raged around them, these letters have been kept safe by the Australian War Memorial – but now, finally, the nation can read their stories.

They reveal the Anzacs as they actually were.

The writers don’t boast of their bravery, but it’s clear to see on the page.

Watch the video below.

ARTHUR BLACKBURN

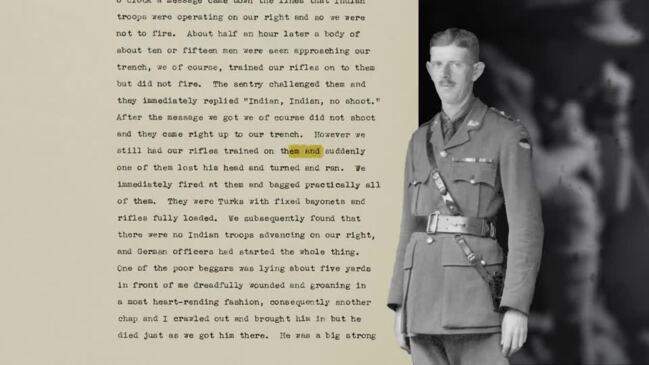

Take the compelling account of the Gallipoli landing written by Arthur Blackburn of the 10th Australian Infantry Battalion in a letter sent to his brother, dated 3rd June, 1915.

Over eight typed pages, the then Private Blackburn (later a Brigadier, and a Victoria Cross recipient) describes days of utter hell, beginning with the almost unbearable tension of the pre-dawn landing, the desperate clambering up steep cliffs and ridges, being shot at by enemy soldiers “not more than 10 or 20 yards away” (9-18 metres), and an agonising sense life could be snuffed out at any moment.

“I have never been so thankful for night in my life, although when it did come there was very little difference,” Blackburn wrote to his brother.

In another section he recounts a harrowing incident in which a group of Turkish troops claiming to be Indian soldiers tried to access the Anzac trenches.

“The German officers here are up to every trick,” Blackburn wrote, making note of the fact that there were in fact some German soldiers at Gallipoli (estimated to be several hundred). Only when one of them “lost his head and turned and ran” was the plot foiled, he added.

For others, fortunes were more mixed.

Watch and hear his letter read out below.

JOHN CROFT

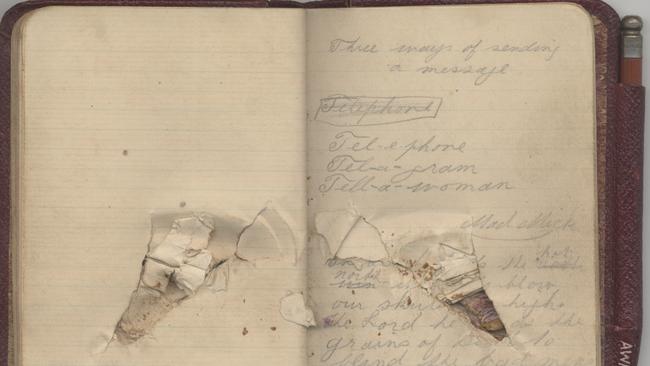

Private John Croft’s life was saved when the small diary in his pocket took the bullet that might otherwise have killed him.

But in a letter to his brother, written from a hospital bed, Croft revealed it was not a miracle escape.

“(I) got a bullet through the arm several hours after landing. It was only a small wound but it cut the sinews, and my hand has been very near useless ever since,” he wrote.

“I have been in bed for 18 days so I shall soon be getting up and going to a convalescent home for a spell and then back to the trenches.”

His tone is hard to pin down as he recalls the events of the landing at Gallipoli, saying “we had a pretty lively time” and describing it as “a day I shall never forget”.

In other letters, the horrors of war unfold gradually, with jingoism and enthusiasm giving way to despair and disillusion.

ROBERT ANTILL

On April 23, 1915 – just before his deployment to Gallipoli – Corporal Robert Edmund Antill of the 14 Battalion wrote to his “Dear Mother and Father” saying “I am fit as a fiddle and ready for the fray, which is not far off.”

But in his next letter, dated May 14, the tone has shifted dramatically.

Corp Antill reported that he is “still alive,” having “had some of the most marvellous escapes a fellow could have”.

“(But) I will be highly delighted when this war is over for it is simply terrible to see your pals shot down beside you,” he wrote.

HAROLD ELLIOTT

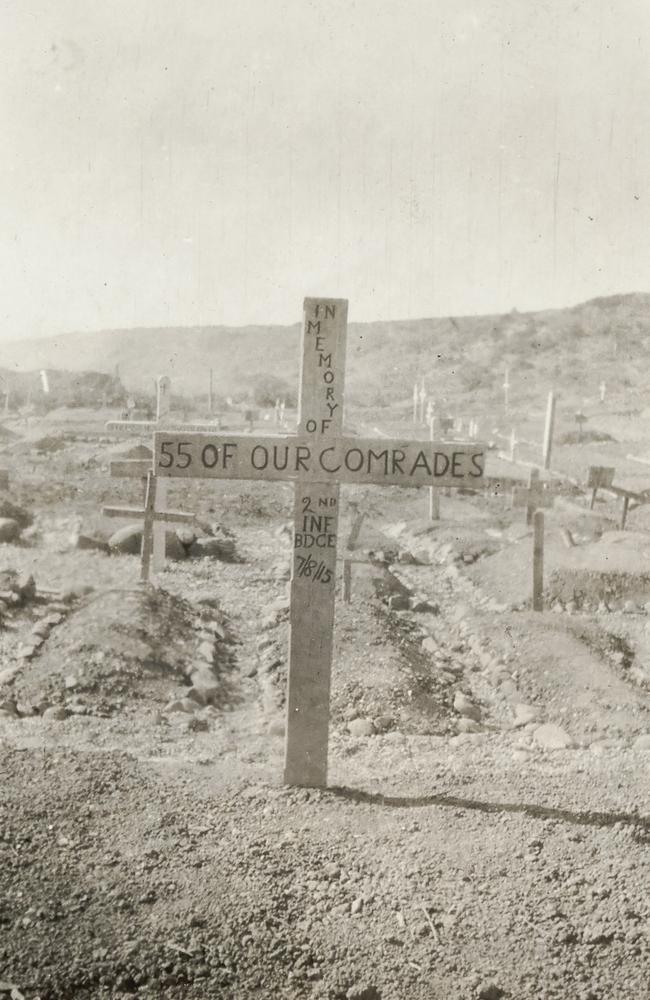

Some of the worst horrors from Gallipoli were captured by the celebrated World War One Brigadier Harold Edward ‘Pompey’ Elliott, in letters to his wife.

Describing the aftermath of a battle, Elliot wrote: “Afterwards men lay for a couple of days and in some cases when they got here the stench from their wounds was awful and they did not seem to have sufficient doctors aboard the ships.

There were nearly 200 men in some cases on a ship and only three doctors and no nurses, and the men suffered dreadfully.”

Historian and author Ross McMullin said Elliot had a “no secrets pact” with his wife.

“He was exceptionally frank and forthright in his correspondence during the war, including from Gallipoli, about what happened to him and the men he was commanding. He was exceptionally frank and forthright about what he felt,” Mr McMullin said.

JOHN MONASH

Another celebrated veteran of the Gallipoli campaign, General John Monash, was just as open in his letters to his wife Hannah.

In a letter penned on the eve of the landing, he grappled with the prospect of his death, saying his “one regret” is the grief that it would cause his family.

But “with the full and active life I have had, I need not regard the prospect of a sudden end with dismay,” he wrote.

Robyn Van Dyk, head of the War Memorial’s Research Centre, said the first-hand accounts from the soldiers often contrasted sharply with newspaper reports, but they arrived much later.

“It was all heroics in the newspapers. The bad stuff took a long time to wash through,” she said.

But many of the letter-writers did self-censor. The soldiers were acutely aware their words would be checked to ensure they did not reveal information about positioning, planning or troop morale – intelligence which could be costly if it should fall into enemy hands.

FRED BIDDLE

In his letter dated May 29, 1915, Captain Fred Biddle from the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade assured his mother “I am in splendid health and have so far not stopped any bullets”, but immediately warned: “There is so much I could say which would not pass the censor that I hardly know what to write”.

Ms Van Dyk said she was struck by how different the writers seem from a modern sensibility.

“When I read Second World War letters I definitely feel like they’re more modern, like us,” she says. “When I go back to the First World War, it’s a very different type of person.

They’ve very volunteer; they’re not very military in that way. But they were really brave and they had a certain character to them. They were a little bit rough, a little bit not-in-awe of the British higher-ups, and they’ve got that larrikin thing going on. But they’re also pretty respectful of their parents.”

As for their thoughts on their own service, Ms Van Dyk said the letters reveal a range of viewpoints.

“You’ll find a whole lot people who are in the zone of survival, doing their best for their beliefs,” she said. “And they’ll often [state] in their letters why they’re there, why they enlisted. Generally that can be fighting for freedom, or their country.

“They’ve got a sense of high belief in what they’re there for.”

Truly something never to forget.

They shall grow not old,

as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them,

nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun

and in the morning

We will remember them.

We will remember them

Lest we forget

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

New faces of parliament; Lambie fights for political life in Senate

These are the new faces of Australia’s next parliament, as Jacqui Lambie fights to keep her position in the Senate with votes being counted.

WATCH: Albo tells dog ‘don’t bite the PM! … they’ll shoot you’

Anthony Albanese probably didn’t think he’d meet with his critics so soon after re-election, but a canine buddy brought the PM back down to earth. SEE THE VIDEO.