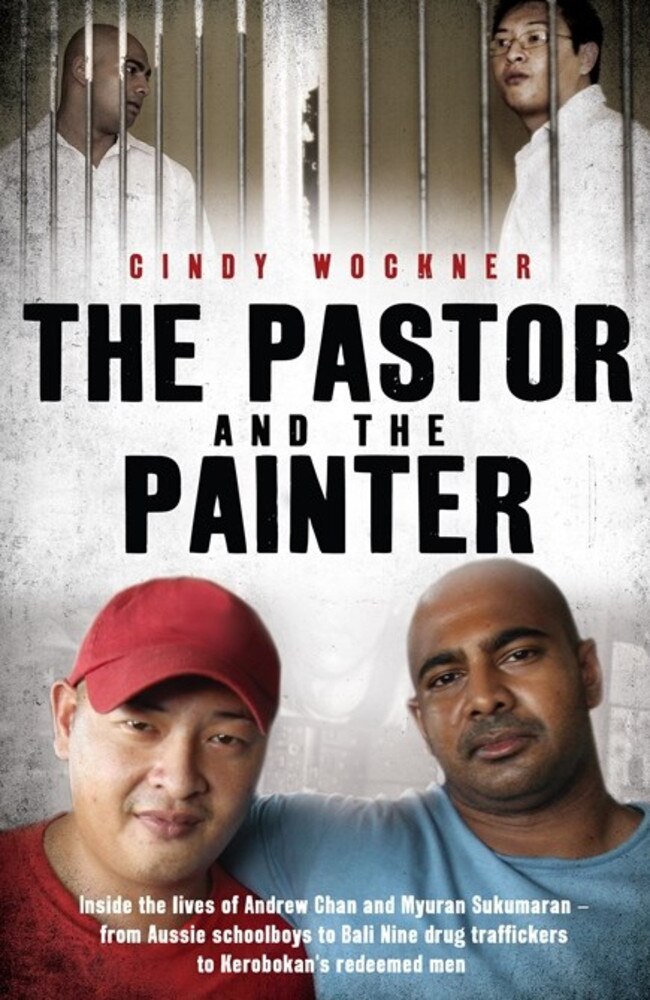

Final moments of executed Bali 9 pair Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran revealed in new book: The Pastor and the Painter

BOOK EXTRACT: Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran were on their last ever flight. There was little chance to look out the windows and see Bali. This is how their final days unfolded.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE LAST FLIGHT

‘Thank you for choosing Wings Air. Hope you have a pleasant flight. In front of you, you will see an exit door ...’

The flight steward, in a short red skirt and black stockings, demonstrated the safety features of the plane. She pointed out a safety card in the seat pocket, which contained, among other things, prayers from various religions, should there be an on-board incident and passengers felt the need to pray. And all this she said with a straight face. Perhaps the absurdity of it had not registered. Or perhaps she was, as Myuran thought, terrified of him and Andrew.

‘Here are the exits, should you need to escape ...’

There wasn’t much chance of that, Myuran thought, since he and Andrew were in handcuffs and shackles, and surrounded by heavily armed paramilitary policemen in balaclavas. In fact, the plane was packed with police and prosecutors. Some took selfies with the now infamous Australians.

After weeks of speculation, Andrew and Myuran were finally on the plane to Nusakambangan. In the end, the government had decided to charter a commercial airliner for the flight. Escorting them from Bali to Cilacap, in Central Java, were the fighter jets they had seen several weeks before. For the two Australians, it was their first time on a plane in a decade. The last had been in 2005, when they travelled from Sydney to Bali in preparation for their ill-fated drug run.

MORE: Australians behind bars in Indonesia revealed

MORE: Australians executed overseas in foreign lands

MORE: Myuran Sukumaran’s best friend and confidante

As dawn broke on Wednesday, 4 March 2015, the sky above Bali turning a delicate shade of pink, the Wings Air plane sat at the end of the runway and waited, engines running, propellers turning. The holdup was not explained. Someone said it was because one of the fighter jet escorts had had a mishap back at the hangar; apparently its parachute had deployed accidentally. Two fighter jets had already taken off. Finally, the third fighter jet taxied around in front of the red and white Wings Air plane and hurtled down the runway. Wings Air took off after it.

Andrew and Myuran were on their last ever flight. But there was little chance to look out the windows and see the majestic scenery of Bali — the beaches, Mount Agung, Kintamani. It had been a long time since they saw any of that. The prisoners truly believed they were going to be executed soon after arriving at their destination. On the plane with them were 20 BRIMOB officers and another 30 or so prosecutors and officials.

Before they had taken off, senior Bali police officers — men who would not be making the journey with them but who had organised the transfer — took selfies with both Andrew and Myuran. ‘Smile, smile,’ one officer said to Andrew. Myuran felt like every person on the plane took a photo with him during the trip.

When these photos later found their way into the media, the Australian government was horrified. It was like some kind of ghoulish circus. Then there was the spectacle of the fighter jet escort. No other prisoner being taken to Nusakambangan had been accompanied by such a show of military might.

Such was the security that Andrew and Myuran were not even permitted to use the toilet during the flight. When one of them needed to pee he was told he would need to do so in a water bottle, sitting in his seat. A giggling guard held the bottle for him as he urinated. Then the policeman had to ask his boss to discard it in the toilet. Both Andrew and Myuran were held by the arm all the way.

Andrew dozed off for part of the journey. It was impossibly hot. Unable to take off his jacket because he was shackled, he was sweating profusely. The armed officer next to him gave him a hankie to wipe away the perspiration.

As they landed, the ‘too cute stewardess’, as Myuran called her, made another announcement. ‘Welcome to Cilacap. I hope you enjoyed your flight. Please do not leave any of your possessions behind.’ She reminded them that the time in Cilacap was one hour behind Bali.

—

When the lawyers were finally able to visit them at Nusakambangan, Andrew stared at Veronica as if he didn’t recognise her. Then she realised — he wasn’t wearing his glasses or contact lenses. He couldn’t see. He walked to Veronica and started hugging her, squeezing her tight. The hug went on and on. Knowing that security cameras were recording everything, Veronica started to feel uneasy: such a long hug wasn’t normal in this culture.

Andrew whispered in her ear. ‘I’ve got something for you — can you take it, please?’ He passed her some pieces of paper — his goodbye letters for his family.

He and Myuran were angry and wanted to know where the lawyers had been. Raheem, a Nigerian prisoner in the same cell block, had been visited by his girlfriend yesterday but no one had come to see them.

‘Why couldn’t you come?’ Andrew asked. ‘If you guys didn’t come, I was planning to do a hunger strike for two days because the other guy got a visitor.’ Things were dire and no one knew what was going on.

Still, the Australians hadn’t lost their sense of humour. At Kerobokan prison, Andrew had been diligent about replying to every letter he received. Myuran, always busy painting, hadn’t — and now he felt bad about that. ‘Can you redirect my mail so

I can answer them now that I have time?’ he joked. And he wanted to know why he didn’t get lamingtons. ‘I’m shocked I didn’t get lamingtons,’ he told the lawyers. ‘Being on death row is a lot more fun in Bali.’ This point was further illustrated when

one of the guards had told them that sometimes cobra snakes found their way into the toilet. It was a frightening prospect they shared with their lawyers.

—

When I spoke to Myuran the night before they left Bali he was calm but despondent. His voice was flat, resigned. All he wanted was for his mum to be proud of him. He was upset that she was now so stressed and in such pain. He wished he could take it away. Most of his belongings had already been taken out of the prison by his family, he said, in anticipation of this day. He had already sorted out who would take over all the rehabilitation projects once he was gone, and how he hoped they would continue.

He lamented that all his work on the projects now meant little: ‘They say it’s all really good but it doesn’t mean anything in the end.’ Over the past few days he had painted portraits of some of the people in charge of his fate — the chief prosecutor,

the minister of justice and human rights, the attorney-general. But he hadn’t yet thought about what he would ask for when the time came for his last request. It was all too hard.

Myuran spoke of his life over the past ten years, joking that he could write a TV reality show about what went on inside Kerobokan jail. People would never believe it, he told me, but it would rate like crazy. Like the time a cake was brought in for the departing Schapelle Corby. Pictures of the cake — which only arrived after she had already left the jail, and which she therefore never actually saw — ended up in the women’s magazines, which were desperate for any titbits about her last days at Kerobokan. The money earned from the sale of those pictures went into the prison kitty to help fund the rehabilitation programs. Myuran hadn’t arranged any of it but was happy to get a funding windfall from what was essentially a fabricated story. The guards enjoyed the cake and everyone laughed themselves silly at how gullible the press could be.

Somehow, Myuran had managed to run the rehabilitation projects and navigate the prison bureaucracy at the same time, as well as keeping any drug merchants out of his art studio. He abhorred the dealers and the gangs who ran the jail. And he had a short fuse, as fellow Bali Nine member Renae Lawrence found out once when the pair argued.

Myuran told me he and Andrew were sorry: they had stuffed up, but they didn’t deserve this. ‘We made a mistake, a lot of bad things have happened and we have changed,’ he said. ‘We made an effort and have done so much work inside here.’

No one he spoke to that night knew what to say to him. Most thought it could well be their final time with Myuran. It was 11.03pm when my conversation with him ended. I didn’t want to say the word ‘goodbye’ — I didn’t know what to say. I made small talk as I tried to think of something. In the end, I said the only thing I could bring myself to say: ‘You take care, Myu.’

—

That night, Andrew was trying to keep his humour up. ‘I’m busy like Tiger Airways right now, so many calls an[d] text[s],’ he joked. ‘It’s like the customer service line.’

He was busy writing, he said, wisecracking with me via text message about how he might finally write an article that would be published in the newspaper— it was a ‘golden opportunity to put my own article up’, he joked. ‘UR gonna miss me being a complete smart-arse now,’ he told me, saying he would lose his phone when he got moved. He signed off, promising more dealings in the future.

*The Pastor and the Painter: Inside the lives of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran from Aussie schoolboys to Bali 9 drug traffickers to Kerobokan s redeemed men by Cindy Wockner is published by Hachette Australia and available now for $32.99.