Division over cashless debit card continues as Labor under pressure to reinstate the welfare scheme

There are calls for the cashless debit card - which limits what a person can buy - to be rolled out for all Australians who receive welfare support.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A regional council wants the cashless debit card reinstated for people deemed “vulnerable” or “at risk” due to violence, alcohol and gambling addictions, amid reports of a spike in harmful behaviour since a trial welfare scheme was scrapped.

The Coalition has called for a full reinstatement of the income management card in the four communities where it was trialled for six years before being abolished by the Albanese Government in 2022, seizing on a new report based on more than 100 interviews with stakeholders warning of an increase alcohol and gambling “misuse” since then.

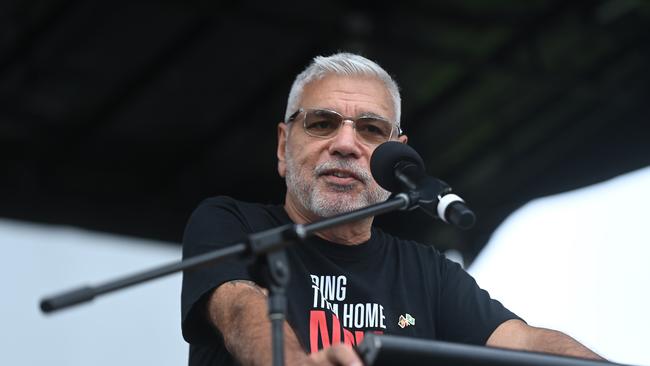

Aboriginal leader Warren Mundine has gone a step further and said the cashless card should be rolled out nationally, insisting the government should be “doing what we know works” to address disadvantage.

“I’d like to see all Australians who are unemployed and on welfare to be on (a cashless card) quite frankly, not just Indigenous people,” he said.

Meanwhile Labor has pointed to the report concluding there was no clear “causal” link between the end of the card and reported increases in problems like alcohol use and child neglect.

Reaching for a compromise is Ceduna Mayor Ken Maynard, who said councillors in the South Australian town where the card was trialled have written to both Labor and the Coalition seeking support for new targeted approach.

“We would like to see an introduction of a card to be given to people that are considered in a vulnerable or at risk situation, “ he said.

Mr Maynard said welfare recipients who were capably managing their finances would avoid “stigma,” while those showing “repeat behaviours” would be subject to the tighter restrictions.

He said any new version of the system, which previously quarantined 80 per cent of a welfare recipient’s pay so to a card that could not be used for things like alcohol or gambling, should also apply beyond the trial towns to account for seasonal population movement.

“My gut feeling was if the card was achieving its aims in six years of trials it would have been made permanent,” he said.

Coalition Indigenous Australians spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price said the report confirmed the cashless card program had been the “difference between a child having food to eat or not”.

“This has gone beyond a matter for debate, and the government’s refusal to reintroduce measures like the cashless debit card should completely discredit them from running this country,” she said.

Ms Price said children should not be starving in Australia.

“The fact that this is happening when we have a proven way of ameliorating this harm is abhorrent,” she said.

Labor poured $174 million in extra supports into the ex-trial communities of Ceduna, East Kimberley, Goldfields and Bundaberg-Hervey Bay when the cashless card was abolished.

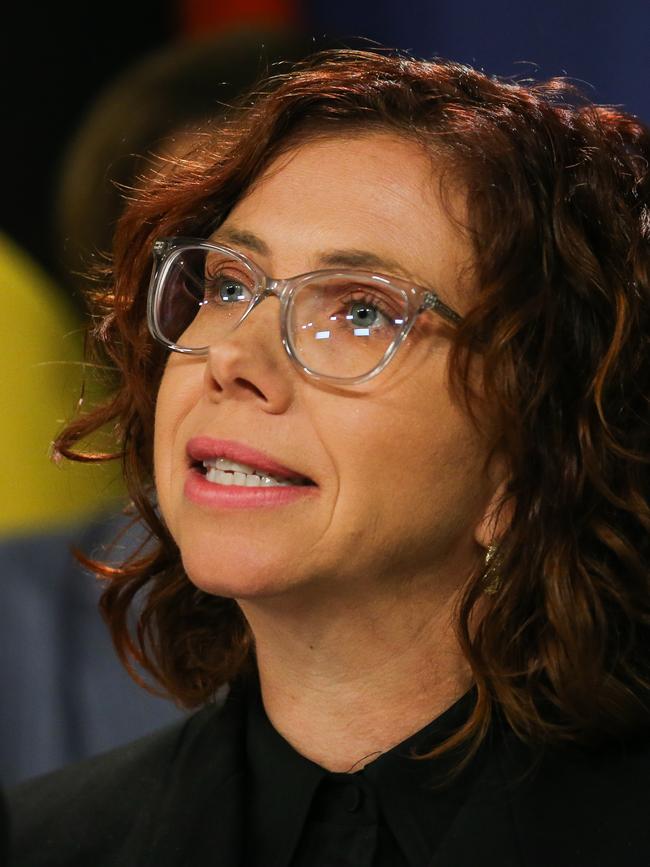

Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth said there was a “mix of views” on the card program ending and the report had no data to support a link to increased harms.

“The review itself states ‘no causal statements can be issued from the analyses’ and that at the time of the interviews there were a number of factors in play in communities,” she said.

Ms Rishworth said there were “complex, intergenerational issues” across remote and rural Australia.

“These are issues our Government works collaboratively on with state and territory governments to address,” she said.