A WWI bridge, a Vietnam tunnel rat and a troublesome tearaway whose courage won the day

How many Aussies does it take to surround and overcome 40 well-positioned enemy? Just two, if one of them is troublesome tearaway William Campbell.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“The Germans thought they were surrendering to the entire British Army – it was just two Australian sappers!”

A Vietnam veteran’s “obsession” with honouring his fellow combat engineers from an earlier conflict came full circle overnight at a unique event: the dedication of a new memorial bridge at Amiens, France.

The city is a key location in the Anzac story and the setting for an extraordinary chapter, involving a tearaway Aussie, two courageous comrades and another bridge.

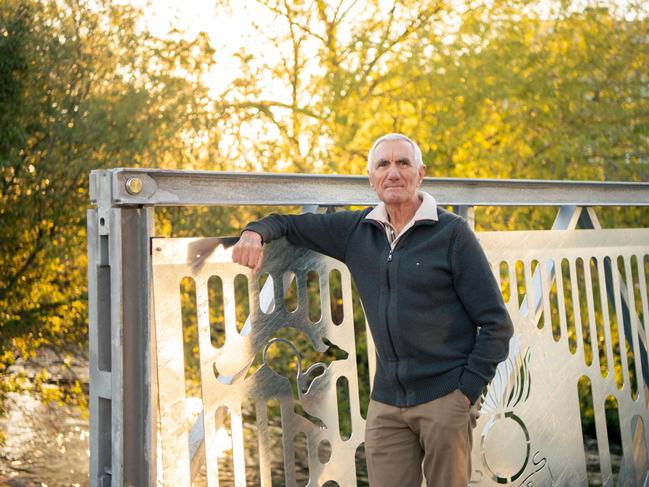

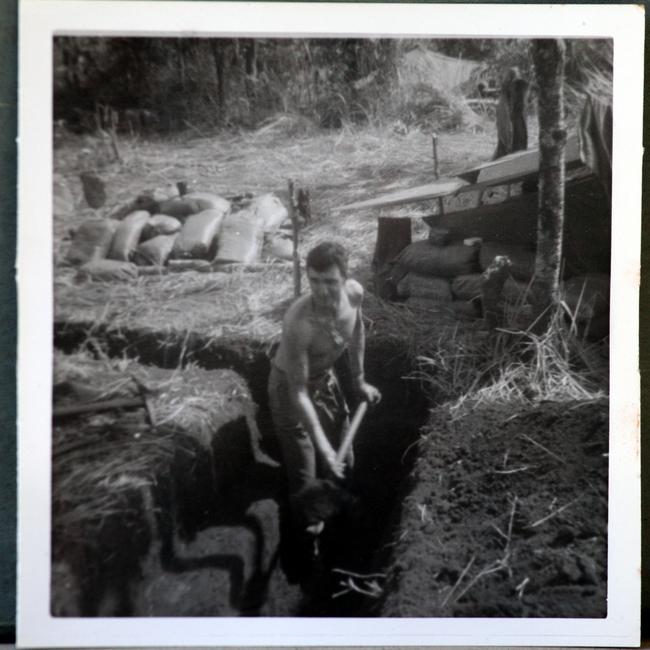

Lt-Col George Hulse, who survived hideous underground warfare as a “tunnel rat” in South-East Asia, became involved in the Bridge of Friendship project out of determination that the role of engineers in battle – especially in World War One – be better known and commemorated.

“One of our mottos is ‘Ubique’,” Lt-Col Hulse said ahead of last night’s ceremony. “That means ‘Everywhere’.”

Never was that more evident than on August 8, 1918, during the Battle of Amiens: a stunningly successful Allied advance spearheaded by Australians and Canadians that smashed far through German lines and into the open country beyond, leaving the enemy reeling.

It was the beginning of the end of the war; German commander General Ludendorff called it “the black day of the German army”.

Amid heavy casualties on the Allied side, extraordinary feats of courage and initiative were displayed by men of all units – among them a troublesome larrikin whose actions that day would more than redeem his reputation.

Sapper William Campbell, who previously had been disciplined for drunkenness, vandalism and going absent without leave, was in a team from the Australian Engineers’ 12th Field Company briefed to build pontoons over the River Somme, a formidable obstacle to the advance, as battle raged around them.

But instead they found an intact bridge at the small village of Cerisy and dashed across, with rifles rather than toolkits: six men under a corporal, ready to hold the valuable position against any counter-attack.

“Then all hell broke loose about 500 metres to the north and the corporal thought he was in real trouble,” said Lt-Col Hulse, of St Lucia in Queensland. “There were two heavy German machine guns, protected by an infantry platoon.”

Campbell, of Daylesford in Victoria, was sent forward to scout with Sapper Arthur Edwin Dean, of Moonah in Tasmania. They saw the machine-gunners plus about 30 riflemen were targeting British infantry and “chopping them to pieces”.

“The two sappers just couldn’t believe it. They had to do something. So using soldier skills, they got up behind the German position, threw some grenades, fixed bayonets and charged,” said Lt-Col Hulse.

“The German lieutenant thought this was it, he’d been surrounded. And so he surrendered. He didn’t realise he was surrendering to two Australian sappers, not the rest of the British army.”

An official report backed up the feat, underscoring that the duo “dashed several hundred yards across the open under intensive rifle and machine gun fire”.

It continued: “The act of signal courage relieved the situation at a very critical time, undoubtedly saving many lives … these troops were then able to advance about half a mile without much opposition, thus clearing the approaches to a bridge in the vicinity, and opening up the first lateral communication across the Somme”.

Campbell, 24, and Dean were both nominated for the Victoria Cross, along with their commanding officer Lieutenant Ralph Alec Hunt, 27, of Brighton, Victoria, who earlier in the mission had carried a wounded man 200 metres to safety while under fire. “They were the only engineers nominated for this award in the Great War,” noted Minister for Veterans Affairs and Defence Personnel Matt Keogh, representing the Australian Government at the dedication.

Ultimately, Hunt was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Campbell and Dean were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

“It’s a bit of a shame, because they thoroughly deserved their Victoria Cross,” said Lt-Col Hulse, adding that the downgrade was probably not because of Campbell’s past missteps and more likely because there were so many recommendations for the VC that day the British commanders “had to put a line through some”.

In an interesting footnote, while Dean went on to be promoted, Campbell – who in 1917 suffered the misfortune of being accidentally shot in the leg – went absent without leave again a month after the war ended, earning another field punishment.

“He was a bit of a tearaway, but not out of character for the rest of them,” acknowledged Lt-Col Hulse.

Having started out as an infantryman then become an engineer, Lt-Col Hulse is a man who recognises bravery, determination and service. In addition to being a combat veteran and former President of Toowong RSL, he became an Ironman last year aged 80; and will compete again this year. “I’ve been very lucky in my life,” he said.

The mission to create the new Bridge of Friendship Between Australia and France – a military-style footbridge, twinned with a similar monument in Toowong – involved raising almost $200,000 in Australia, a bridge donated by the current Royal Australian Engineers, and a separate sum contributed by Amiens City Council, who were “very supportive”. Lt-Col Hulse stresses he was just one part of a team who made it happen.

It is the first overseas monument to all Australian sappers of WWI: not just the men of August 8, among them some who daringly captured an enormous German rail gun now held at the Australian War Memorial; but also those who dug and fought under German trenches earlier in the war; some of the first men slain at Gallipoli in 1915; and even the last four Aussies killed in combat, seven days before the war ended on November 11, 1918. All were engineers.

In the words of Lt-Col Hulse: they were, indeed, everywhere.

More Coverage

Originally published as A WWI bridge, a Vietnam tunnel rat and a troublesome tearaway whose courage won the day