‘It still motivates me’: Linda Burney reveals deeply personal reasons behind push for Voice

In an exclusive interview, Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney has revealed the personal reasons behind her push for the Voice, and how she deals with criticism of her approach.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dressed in a white linen tunic draped with a long scarf in the red, yellow and black of the Indigenous Australian flag, Linda Burney cuts a striking figure against the sodden bush backdrop of her surrounds.

The federal Indigenous Australians Minister – the first woman and only the second Aboriginal person to hold the role – is in the remote Northern Territory community of Kalkarindji. She has come to meet with locals recovering from months of devastating floods.

The trip to the remote town some 800km south of Darwin, is also an opportunity to hear from Gurindji Traditional Owners and other community leaders about the myriad social and economic difficulties they face, from inadequate housing to a lack of local jobs.

At the school building temporarily repurposed as a co-ordination point for the recovery effort, elders, councillors and other leaders sit around a table on colourful plastic chairs and put their cases to Burney.

“When the floods came, we didn’t have enough locals trained as SES to do search and rescue,” one resident tells her.

“Women don’t like coming to the domestic violence shelter because they are fearful child services will take their kids,” says another.

Burney, 66, patiently listens to their concerns and provides what answers she can, while in the background her staff members take copious notes on various things to follow up. Later, as everyone shares a hot cuppa and some freshly cut sandwiches, the conversation turns to the proposal to constitutionally enshrine an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament.

Burney seizes the opportunity to answer questions and hear the thoughts of the local community.

Some residents are committed to the Voice, while others wonder what it can deliver.

This is a community that is no stranger to the power of Indigenous activism.

Just down the road is Wave Hill, where almost 50 years ago Vincent Lingiari led 200 Indigenous stockmen and their families to walk off the then-cattle station, protesting poor pay and conditions.

Lingiari secured a watershed victory for Aboriginal land rights in a display of courage and patience, events that later inspired Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody to pen the beloved song, From Little Things, Big Things Grow.

It’s an achievement the Yes campaign are hoping to emulate.

Thousands of kilometres away in Canberra, critics of the Voice would argue that developing responses to the “practical” needs of communities like Kalkarindji are more important and meaningful than any advisory body.

Burney rejects this notion, saying the Voice itself can be the vehicle for delivering better practical outcomes for Indigenous Australians by ensuring their needs and ideas reach the corridors of power.

Quite simply, she says, it’s about asking the people you’re trying to help what they actually need.

In 2021, the Gurindji Aboriginal Corporation signed a three-year Local Decision Making (LDM) plan with the Northern Territory government and the commonwealth, that mapped out the community’s priorities.

These included constructing a men’s shed, upgrading the local sports oval, increasing skills training for local jobs and getting more of a say in housing planning and design.

Burney says LDMs, which are unique to the Territory, are an example of the types of existing grassroots structures that could feed into and be elevated by a Voice.

“It’s about making sure that the decisions that are being made in Canberra have the perspective from local communities about what that’s going to mean,” she says. “I envision it will fit into existing policy work in a very real way.”

But before any of that can happen, Burney needs the referendum to pass.

Back in Canberra the political fight over the Voice intensifies with each day.

Burney is now frequently targeted by the Coalition during Question Time as the Opposition seeks to expose any weaknesses – real or perceived – in the Yes campaign.

As she gives her answers standing at the dispatch box on the floor of parliament, Burney’s responses can range from clinical and succinct, to eloquent and passionate rebuttals of the Coalition’s claims.

But no matter the tactic deployed by her opponents, Burney does not allow herself to be drawn into the No side’s characterisation or framing of the Voice.

In dealing with the hyper-partisan debate, Burney says she turns to the advice of Michelle Obama – “when they go low, you go high”.

“You stay true to the people whom you’ve consulted with, you know what they’ve told you, and you just stay absolutely focused no matter what’s happening,” she says.

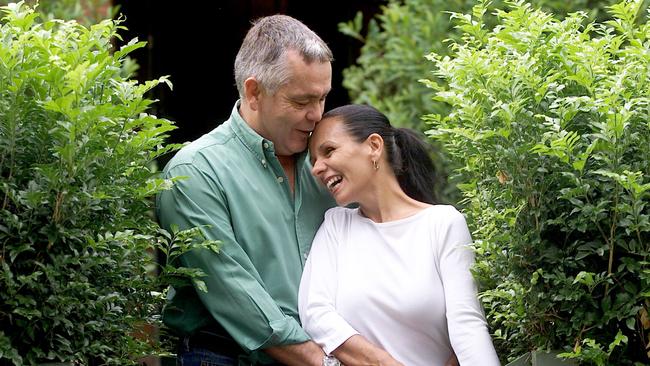

Burney has endured deep personal loss in her life. There was the sudden death of her first husband Rick Farley who suffered a brain aneurysm on Boxing Day in 2005 and passed away a short time later. A mother to daughter Willerui Ngurumbi Karramarra and son Binni Dironbirong, tragedy struck Burney’s life again when at 33 Binni lost a long struggle with mental illness and died by suicide.

The Voice debate is deeply personal for Burney, who recently recounted the death of her friend Michael aged just 44 from serious health problems that led to end-stage renal failure, saying “his Aboriginality condemned him to an early death”.

“I visited him every day in hospital. I watched him go blind in one eye,’’ she says. “I remember the injustice of it. And it’s what still motivates me to this day.”

Burney’s unwavering focus on the end goal and commitment to those she has vowed to represent is informed by decades of experience in government and the public service that included numerous “firsts” for an Indigenous Australian.

A Wiradjuri woman, Burney grew up in Whitton and Leeton in the NSW Riverina, where she was raised by her spinster great aunt Nina and bachelor great uncle Billy. Her mother had fallen pregnant to an Aboriginal man and skipped town to escape the scandal so Nina and Billy took her in, raising her alongside her white cousins in a move she now sees as brave.

Burney started her career as a primary school teacher in western Sydney, during which time she caught the attention of the department and was tapped to work on Indigenous education programs.

From there she became head of the NSW Aboriginal Consultative Group, which led to Aboriginal studies being introduced, and she was later appointed director-general of the NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

In 2003, she was elected to the NSW parliament as the state’s first Indigenous MP.

Thirteen years later Burney – who lives in Marrickville – was elected to federal parliament in the seat of Barton, in Sydney’s west, becoming the first Indigenous female member of the House of Representatives.

Overseeing a successful referendum as Indigenous Australians Minister would be the biggest first of all. But the odds are stacked against Burney and the Yes campaign.

Only eight of the 44 referendums held in Australia since Federation have passed, and no referendum has passed without bipartisan support from the two major political parties.

Of all the arguments mounted by her Coalition opponents against the Voice proposal, criticism that the advisory body is dividing the nation particularly angers Burney.

“The whole point of the Voice is to unify Australia,” she says.

“What is also inescapably and wonderfully happening is more and more people will know the truth about our history, more and more people are celebrating the fact they know what country they live in.

“The amount of non-Aboriginal people that contact me and talk to me, in the supermarket even, just saying that we’re with you and it’s about time we understood things, is just enormous.”

Burney says there is a “huge groundswell” of people and organisations who believe the Voice to be “really important” for “all Australians”.

As Prime Minister Anthony Albanese edges closer to formally announcing the date of the referendum – widely anticipated to be in mid-October to avoid any major sports grand finals or the wet season in Australia’s north – the Yes campaign is picking up speed.

Megan Davis, Uluru Dialogue co-chair and a key architect of the Voice proposal, is one of several prominent Indigenous Australian activists out in the community educating people about the referendum and how it came about.

“It’s six years since we were at Uluru when the invitation was issued to the Australian people,” Davis says.

“So really this referendum is eight years in the making.”

Davis, a professor of law at the University of NSW, says the Voice proposal came from a “really robust sample” of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from across the country.

“They decided a Voice would be a meaningful form of constitutional recognition for First Nations people,” she says.

While Davis understands the role politicians must play in a referendum, she firmly believes a successful referendum is dependent on supporters outside the Canberra bubble talking directly to the Australian people.

“Given that most Aussies and most black fellas know that the politicians and the parliament have failed to address the issues facing First Nations people, we always knew there would be this difficult period for the Voice where it enters the realm of politics,” she says.

“But once the question and the amendment was settled, we’re able to get on with the job of continuing this discussion with the Australian people for a yes vote.”

Experienced and well-known activists and scholars are not the only ones hitting the open road to sell the Voice to Australian voters – a new younger generation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders is emerging.

Yes23 spokeswoman Jade Ritchie, 39, dials in from the North Queensland town of Mackay one Saturday afternoon to provide an update on the information sessions she and fellow campaigner Thomas Mayo have been holding in regional parts of the state.

Ritchie, a Gooreng Gooreng woman who grew up in Bundaberg but now lives in Darwin, is eager to share stories of her time on the road in places like Gladstone, Cherbourg and Rockhampton.

“The aim is simply to inform people, to make sure that any gaps in information are filled with truth,” Ritchie says.

Misinformation is the enemy, and combating it has proven a “huge task”. In order to give it her all, Ritchie has taken a leave of absence from her job to campaign full time for Yes23. The organisation also has more than 20,000 volunteers around the country. “We are throwing the kitchen sink at this,” she says.

Despite almost every poll consistently showing support for the Voice is weakest in Queensland, Ritchie says she has witnessed “so much goodwill” from residents, and is “seeing hearts and minds open across Queensland”.

Bridget Cama, 28, and Allira Davis, 26, were students when their elders first called for a Voice, and in 2019 the pair – who work in law firms in Sydney and Canberra respectively – established the Uluru Youth Dialogue.

Cama says the aim is to reach out to young Australians and ensure they are informed about the Voice proposal and the looming referendum.

“Young Australians have never voted in a referendum before in our lifetimes, so it really is a once in a lifetime opportunity,” she says.

Polling has consistently shown Australians aged 18 to 35 overwhelming support the Voice, in contrast to older age groups where the No campaign is having a greater impact.

“The Uluru Statement from the Heart talks a lot about hope and a better future for generations to come, and that includes both Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people,’’ Cama says. “We can build a better Australia.”

Throughout 2023, polling trends show support for the Voice proposal has fallen. While No campaigners claim this as proof that once the public engage on the issue they decide they do not want a constitutionally enshrined Voice, those on the Yes side are not writing off any particular state or cohort of voters.

One thing all of the polls show is a vast number of “soft” voters – those who aren’t fully confirmed in their position, more of whom currently exist on the No side. It is these minds Burney, Yes campaigners, the government and premiers across the country will seek to change.

Sitting in his office in Parliament House, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is reflective as he puts the proposal before Australians in simple terms.

“Australians have a sense of fairness, and soon they will have to ask themselves what is the consequences of voting yes or no,” he says.

“If they vote no. Are we going to just do exactly the same thing? If we do the same thing, we should expect the same outcome.”

Albanese says Burney and her predecessors have tried valiantly with the “best of intentions” to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians through Closing the Gap targets, but the statistics show nothing tried to date has substantially shifted the dial.

“I think people do want to see Indigenous Australians have the same opportunity as non-Indigenous Australians, they do want to Close the Gap,” he says.

“But if we do the same thing, we should expect the same outcomes. And that’s why Australians have an opportunity to not vote for the status quo and to reach for the stars and go through a better way.”

In a speech to the National Press Club in July, Burney sought to answer the question of why the Voice was needed.

Her “simple answer” was that the gap was not closing fast enough.

Indigenous young people are 24 times more likely to be locked up, 55 times more likely to die from rheumatic heart disease and more likely to have experienced homelessness than to hold an undergraduate degree.

“This is systemic and structural disadvantage,” Burney says. “The Voice will be a mechanism for government and parliament to listen.’’

Burney reflects on the words of the late Yunupingu, leader of the Gumatj clan of North East Arnhem Land, who once said “they do not listen because they do not have to”.

“It was the truth,” she says.

The Voice, she insists, changes that, and Burney is determined to see it through.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘It still motivates me’: Linda Burney reveals deeply personal reasons behind push for Voice