The moment I realised mum was a killer

HAZEL Baron always knew her family was a little strange, but when her dad died suddenly she suspected it was more than an accident. Then she overheard her mum talking.

Real Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HAZEL Baron was nine when she first suspected her mother was a murderer.

The tall, gangly schoolgirl with short curly hair who wore long socks, wool skirts which came to below her knees and heavy knitted sweaters was already the keeper of too many of her mother’s secrets.

Don’t tell your dad about this. Don’t tell your dad about that. Don’t tell him about the sneaky hours in the dark on the big back seat of the family’s American-built Nash car with young Harry, 19 years her mother’s junior. Harry was only supposed to be “helping with the kids”. As a kid herself, Hazel did what she was told and never even considered telling on her mum. Dulcie was also quick with her right hand to dish out a slap or worse. In those days, no one questioned using corporal punishment to keep children in line.

Looking back, Hazel’s suspicions should have been aroused on the night when her mother, Dulcie, then known as Hazel Dulcie Baron, gave the kids warm milk and Aspro tablets before bed. It was the first time in their lives that Hazel, her brother Allan, eight, and the five-year-old twins, Margaret and Jim, had been given warm milk to drink. Dulcie wasn’t much of a mollycoddling mother, treating her four children more like mini grown-ups. But this had been a big day, she said, and the milk and Aspros would help them sleep. Her attention made them all feel special for a change.

It was the dying days of the winter of 1950 and the Baron family’s home was two old army tents made out of heavy green canvas set up on the northern bank of the Murray River. The breeze coming off the water made the night air even chillier but Dulcie never seemed to feel the cold. As the kids sat with their blankets around themselves, keeping warm by the campfire, Dulcie just pulled the cardigan she wore over her dress closer to her chest. It was quiet and dark as she heated the milk in a pan over the burning logs, the only light the sparks flying up. The ribbons of smoke twisted into the air like ghost gums along the riverbanks. Hazel could just make out the outlines of their two tents a few metres away at the edge of their camp.

Hazel didn’t know where the tents had come from; they just turned up. Dulcie was a wonderful storyteller and she rarely let the facts get in the way. Hazel figured her mum had probably charmed someone with one of her hardluck stories, of which she had many; she had them all down pat and they were invariably successful.

***

Dulcie could conjure up anything from nothing, just like the tents. And the truth.

The reason for the warm milk and Aspros was snoring on a stretcher bed near the tent flap. Wednesday, August 30, 1950 had been a big day because their dad, Ted Baron, 48, had come home from hospital.

The once-powerful railway ganger, who had led teams of tough men doing hard graft across New South Wales and Victoria, was just a shadow of himself. He had arrived at camp that afternoon in a taxi from Mildura Base Hospital, over the Murray River Bridge and down to Buronga. Dulcie had been dutifully visiting him every day for the two weeks her husband was in Mildura Hospital and when he told her that he wanted to go home with her, she seemed suitably thrilled.

Ted couldn’t really afford a taxi fare but, crippled with rheumatoid arthritis, he could hardly get around, even with a walking stick. He had had a tough time of it for a few years, in and out of hospitals in various towns as doctors tried all sorts of treatments, including the newfangled gold injections which were supposed to help the pain and swelling in his hands, feet and legs but to which Ted had an adverse reaction. There was no cure for his condition and he knew it was only going to get worse, something he accepted in a matter-of-fact way as people did in those days, at least the people he knew. You didn’t expect too much from life and took what was given you. Ted was a no-nonsense conservative fellow, not the kind of man to make a fuss.

Ted was still tall at six feet two inches and wore his only suit, a dark brown one, with the pants held up with braces. He would never wear a belt, believing the only “proper” pants were ones with braces. But despite the braces, the jacket and pants that had once fitted his big frame were now hanging loose. His illness, coupled with typical hospital food, had stripped about a stone from what had been a 15-stone frame. But Ted was still a handsome man, his high forehead and hair that was still dark and curly making him look younger than his years even as the pain in his gnarled hands and feet never receded.

He didn’t like that he had been a bit of a poor excuse for a dad in recent years. The twins had barely known him when he had been able to chase them, give them piggybacks and pick them up and tickle them ’til they cried as he had with Hazel and Allan. The two oldest remembered the jokes he would tell, never in bad taste, never using a swear word, but oh so funny.

***

The kids had got used to their dad being in hospital and they surrounded him and walked him back to the camp. While they were happy to see him, their welcome couldn’t rival that of Ted’s dog, Toby, an Australian terrier, who threw himself at his master, whirling in circles at Ted’s feet and whimpering with excitement.

Dulcie was kindness incarnate to her husband that afternoon, fussing over him and making sure he was comfortable, much to young Hazel’s surprise. She gave Hazel and Allan some change and sent them to the corner shop at the end of the gravel road along the riverbank to get the milk and Aspros. Money was always tight and milk was a real treat in itself; they usually drank their tea black. For two shillings (around 20c today), they could buy a loaf of bread and enough hot chips to make chip sandwiches for them all. A family feast. Most nights, dinner was stew made from cheap cuts of meat that were only edible once they had been cooked slowly over the fire or in the camp oven.

***

Ted slouched on the bed soon after arriving back at camp while Dulcie fussed and fluffed about. He may well have wondered what he had done to deserve it but all he could think of was that if he went to sleep, the pain would go away. It was the only comfort he got these days. Dulcie suggested he turn in for the night before the kids did. She told him to stay in what was usually her bed, a camp bed on legs in the kids’ tent, and she would take one of the thin shearer’s mattresses on the floor. Ted got no rest without sleeping tablets, even though they made him snore. As he lay in bed, Dulcie brought him one of their best china teacups full of water so he could wash them down. She pulled the wagga up around his neck and tucked him in at 6pm.

He was sound asleep when the kids got into their beds. Hazel bent down and gave his lined cheek a kiss but he didn’t move. As for the kids, the warm milk and Aspros had the desired effect and they slept like logs.

Hazel’s mum shook her awake the next morning. The flap to the tent was ajar, the shaft of light showing that her dad’s bed was empty. Dulcie was bending over her, her face all teary: “Hazel, Hazel. Your father’s gone. He wasn’t here when I woke up. I think he fell in the river and drowned last night.”

***

Hazel noticed that when the family was alone again, her mum was nervous and on edge. She had heard her mum tell the police Harry was her brother and then Harry said he was Ted’s brother but Hazel knew Harry wasn’t their uncle from either side of the family. She knew enough about life to know that her mother shouldn’t have been sharing the small tent every night with Harry, except of course when her dad was home and she slept with the kids.

Now, Hazel noticed Dulcie and Harry arguing a lot, for the first time in their relationship. A few days after the inquest, Hazel was sitting on the end of her mattress in the tent stitching up a hole in one of the boys’ woollen socks. The other kids were away playing marbles or hopscotch and Dulcie didn’t realise Hazel wasn’t with them.

From inside the tent, she overheard Dulcie and Harry talking about “getting our story right”. For several days, Toby the terrier had continued to bark and howl at the river and would not be silenced.

“If that bloody dog could talk, we would be dead,” Dulcie said. Hazel couldn’t move or she would give herself away. She didn’t even realise that she was holding her breath. She knew she had heard something she wasn’t supposed to have heard.

***

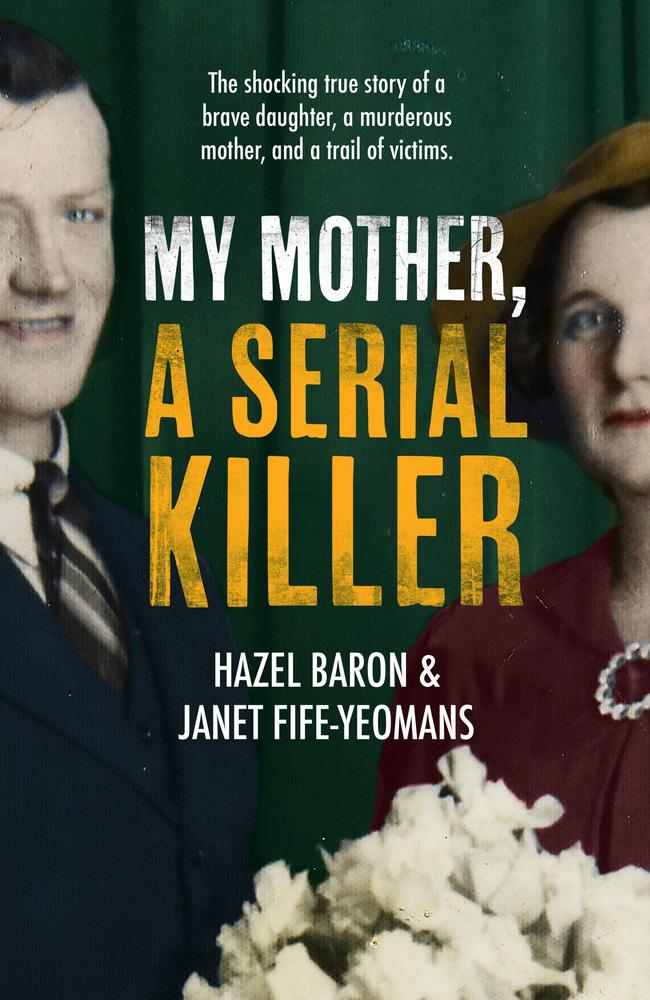

My Mother, A Serial Killer by Hazel Baron and Janet Fife-Yeomans, HarperCollins, $32.99, available in bookstores now. This extract reproduced with permission of HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd.

Originally published as The moment I realised mum was a killer