The fight to rid indigenous communities of drug and alcohol abuse, sexual assault

ABORIGINAL women are speaking up about the wave of sexual and substance abuse in their communities, and demanding that the cycle be broken for future generations.

Real Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HALF a lifetime after being sexually assaulted as a 14-year-old, Jillene Johnson is still scared to sleep.

She didn’t report the person who came into her bed and started touching her that night, and she doesn’t want to name him now, but she also doesn’t want future generations of Aboriginal children to be caught in the same cycle of sexual and substance abuse that diminished her life.

One of several victims of sexual assault who waived their right to privacy and spoke to News Corp National as part of special investigation into child abuse in outback Aboriginal communities, Ms Johnson said she had used pot, ice, “everything”, since the age of 15, in an effort to forget the assault.

MORE: Why blackfellas need a voice in Parliament

MORE: Indigenous disadvantage is driven by a lack of participation

IN-DEPTH: The fight to protect indigenous children from abuse and neglect

Picture Tricia Watkinson

Picking at sores on her arm, Ms Johnson said she was a drug addict, her 11-year-old son didn’t live with her and she was under house arrest.

Bourke’s broad streets are lined with refurbished historic buildings – increasingly home to government and other services – and thick green lawns.

A lot of government money has been poured into the New South Wales town over the last ten years, in a bid to turn its reputation as a trouble spot around.

But home for Ms Johnson is the Alice Edwards Village, over the levy bank, where the houses are falling down and there are no lush lawns, just dust, skinny dogs and car wrecks.

It was once an Aboriginal reserve.

There was not much to do in Bourke except drinking and drugging, and bingo in the village dirt of an afternoon, Ms Johnson said.

High on ice and fuelled by booze, the men and boys in the community got violent sometimes.

“The kids are doing it too because they see the adults doing it,” she said.

So the cycle continued.

In the course of its investigation, News Corp National travelled to the outback New South Wales’ towns of Bourke and Brewarrina and the Northern Territory’s Tennant Creek - where alleged child rapes have made headlines this year.

We spoke with Aboriginal girls and women, as well as to community leaders, social and family violence workers and services on the ground in the towns.

MORE: We must stop celebrating Australia Day on January 26

MORE: Indigenous or not, the same laws apply to us all

In Tennant Creek, chief executive of the Papulu Apparr-kari Aboriginal Corporation and Language Centre Karan Hayward said child sex assaults in her community were so common, the only thing that surprised her about the alleged rape of a two-year-old girl in February this year was that it was widely reported.

“To be honest, what happened to that young one, it wasn’t like it was a shock because we hear it all the time. That one just went to the news. We hear of cases all the time and what’s wrong with us, is that it seems the norm,” Ms Hayward said.

When the Collingwood Football Club visited footy-mad Tennant Creek shortly before the alleged toddler rape, she “gave it to them straight”.

“I didn’t sugar-coat it. I said ‘look I’m sorry but there’s sexual assault and there’s this and there’s all that’,” Ms Hayward, 52, said.

“They were absolutely horrified.”

Since the alleged assault of the two-year-old girl, a four year old in Tennant Creek has required medical treatment following an alleged sexual assault by a teenager and in the Aboriginal community of Ali Curung, near Tennant Creek, a four-year-old boy was allegedly sexually assaulted by a 17-year-old male.

In Halls Creek, in Western Australia’s Kimberly, a 16 year old has been charged with the alleged sexual assault of a four-year-old boy.

Last year in the Northern Territory, 149 sexual offence cases involving children under the age of 16 came to the attention of police. The year before it was 163.

It’s the very tip of the iceberg as most cases of sexual abuse, in both indigenous and non-indigenous communities, are never reported.

Mia Kelly has lived in Tennant Creek all her life.

She said she had never been sexually assaulted but knew people who had.

If her four-year-old son Aaronlee was ever “hurt in that way”, she’d “go psycho” with grief and rage, she said.

MORE: Ten years after saying sorry there is still work to do

CLOSING THE GAP: Indigenous people still being disadvantaged

Ms Kelly told News Corp National she gave up petrol-sniffing at 16 when she discovered she was pregnant for the sake of her child and hoped Aaronlee would one day finish school and get a job.

Perhaps he’d even play AFL and make the whole town proud.

Ms Kelly said she had sniffed petrol “full on” for two years before becoming pregnant - ditching school at 13 - but wanted better for her child.

To keep Aaronlee safe, she kept him with her as much as possible, she said.

When she went out drinking, she left him with trusted family members.

Ms Hayward, who sits on the local alcohol reference group, said “knee jerk reaction” government grog bans introduced in Tennant Creek following the alleged toddler rape were not working, as people simply paid more for alcohol and drank it faster than before.

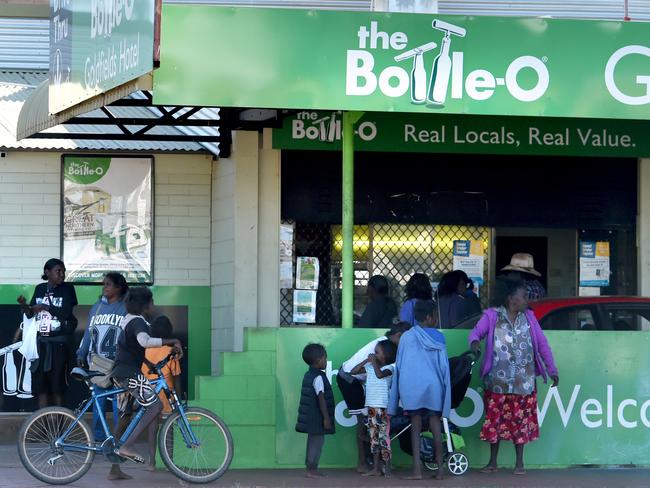

Between 3pm and 6pm most days in Tennant Creek the typically quiet main street filled with families making a beeline for the bottle shop and people were paying a packet for sly grog, brought into Tennant Creek from other states, she said.

“I’ve witnessed … four cartons, four blokes, within 40 minutes,” Ms Hayward said. “They guzzle because it’s a limited time they can get grog and if they guzzle their carton, they can find someone else with a carton and buy and drink that too.”

A five-litre cask of wine bought for $12 in Queensland could be sold for $150 in Tennant Creek and a bottle of wine bought elsewhere for under $5, for $50.

A carton of beer bought for $50 could be sold for $400 while cans fetched $10 each.

MORE: Young girl allegedly sexually assaulted in Tennant Creek

MORE: The Australian crisis we can’t ignore

News Corp observed toddlers walking behind their pushers, so beer cartons could be wheeled home in the short window of opportunity to buy alcohol.

The children joined young and old men and women, heavily pregnant mothers, people on walking frames and in wheelchairs, in lines outside the town’s bottle shops for a box of beer or bottle of spirits.

Alcoholics didn’t stop drinking because there were bans in place, just as signs on the front of houses saying alcohol wasn’t allowed didn’t stop alcohol being consumed by the people who lived there, Ms Hayward said.

It was targeted education programs, not bans, which were needed, she said.

Best known for its ancient Aboriginal fish traps, Brewarrina is situated about 90 kilometres northeast of Bourke and home to about 1600 residents, more than 65 per cent of whom are Aboriginal.

Between the regional centre of Dubbo and Bourke lies nearly 400 kilometres of red dirt.

Flocks of emus, herds of wild goats and kangaroos pepper the landscape.

Bourke hit the headlines in 2013 as the most dangerous town in the world when compared with United Nations data and a 2016 KPMG report states the town has been “characterised as having the highest rate of juvenile crime and domestic violence in NSW”.

Both Brewarrina and Bourke, as their residents joke, are a bloody long way from anywhere.

According to members of the Aboriginal communities in both towns, drug use is rife, with children as young as 10 and 11 smoking dope and many adolescents and teens using ice.

Nearly four decades after she was sexually assaulted by men in the Christian, Aboriginal family that took her in as a child, 51-year-old Narelle ‘May May’ Reynolds said it worried her children were still being abused, and keeping it quiet.

Some were threatened, others bribed, into silence, she said.

Ms Reynolds said she stayed silent for years about the vile abuse she endured; carrying the shame secretly and hooking into grog and drugs in a vain effort to bury painful memories.

“I reckon it’s still happening,” she said from her porch in Dodge City, on the outskirts of Brewarrina. “They keep it quiet out of fear. That’s how it was for me. That’s why I didn’t open my mouth for so many years.”

When she finally reported the assaults in her 30s, Ms Reynolds said she learned other children had been assaulted in the same house.

It gave her a measure of peace to know one of her abusers was in jail and the other dead, but, she said, she wished she had spoken up earlier. It might have saved someone.

According to Bourke CentaCare workers - who provide emergency accommodation, support and services for at-risk women and children – women are scared of their children being removed by government agencies if they admit abuse is occurring in the home.

Team leader of specialist homelessness services Liz Kerr said most Aboriginal women who sought refuge arrived with children in tow, but few spoke of concerns about their safety.

“They won’t disclose violence to children because they are frightened of community services removing them. It takes quite a bit of case management and relationship building before you get anywhere near that sort of thing. They just come to us with their own issues but they won’t talk about their kids’ issues,” she said. “It’s kept very quiet when it comes to kids.”

Ms Kerr said she believed children were coached from an early age to keep quiet about violence at home.

After using drugs for at least half her life in Bourke, Helen Edwards, 41, says she now has poor mental health.

She no longer cares for her seven-year-old daughter and hasn’t seen her 19-year-old son for many years.

She was raped for the first time at age 11, Ms Edwards said.

In the years since, she’s been “raped now and then”, but never reported the assaults.

Asked if she believes children in Bourke are still being hurt the way she was hurt, and keeping it secret, Ms Edwards said she was certain of it.

“It’s all under the radar,” she said. “They never want to talk about it.”