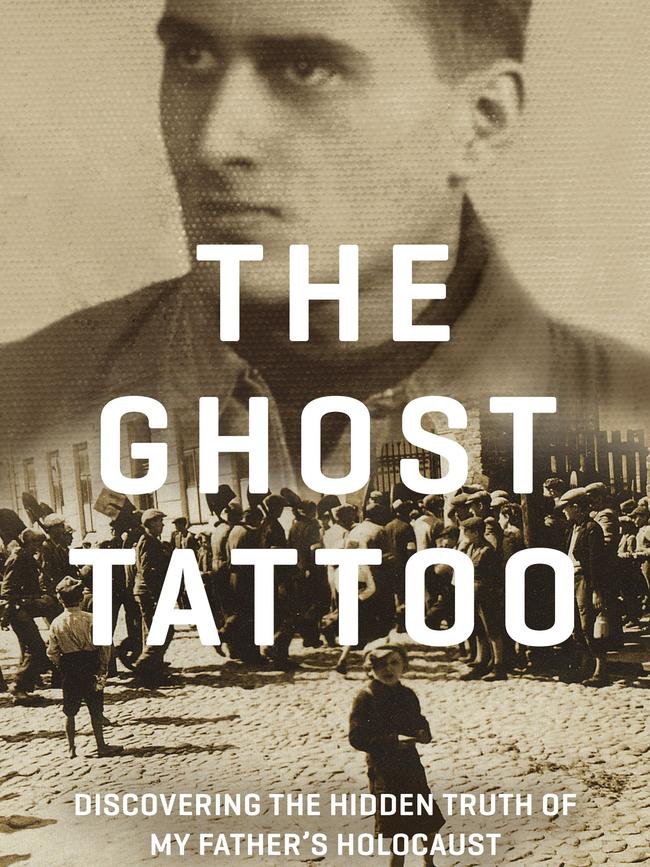

The Ghost Tattoo: New book reveals hidden truth of Sydney doctor’s Holocaust

The son of Holocaust survivor Henry Bernard has revealed what motivated his dad to share his story after six decades, including a role he regretted until his death.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

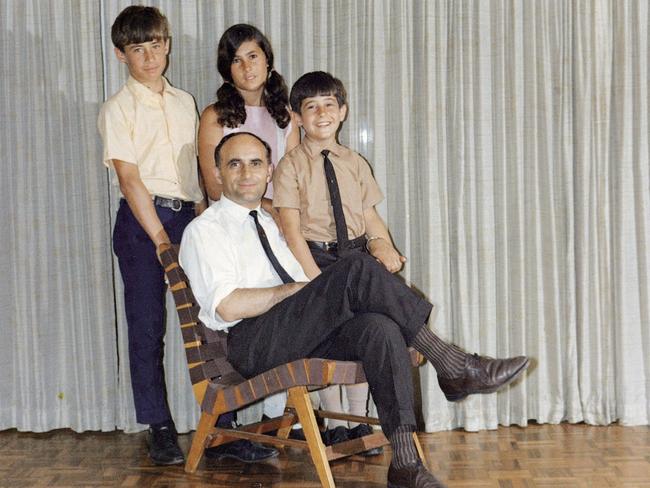

As a little boy growing up in Sydney’s beachside suburb of Narrabeen, Tony Bernard knew his family was a little different. His father, Henry, was from Poland so he had an accent, he liked to eat salami on dark rye bread, he kept a rifle in his bedroom and he was, for the most part, a serious man.

And then there was the drawer in his wardrobe.

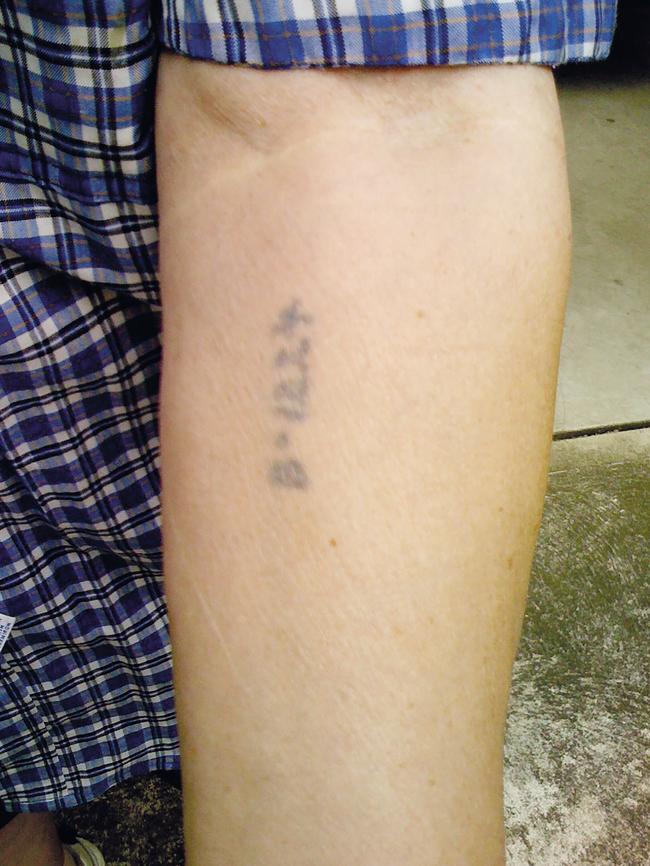

It contained two items: a pair of blue and white striped pyjamas and a black and white photograph of a woman. That, and the strange tattoo of numbers on his left inside forearm, were the only clues that his father, a well-loved and trusted GP on the northern beaches, hid a deeper story.

As a child, Tony knew the bare bones of his father’s World War II experiences, he knew the striped pyjamas and the strange tattoo were mementos of his time at Auschwitz and the woman in the black and white photo was his beloved mother. And that was about it.

While his father didn’t hide the fact he had spent time in concentration camps, he also didn’t talk about his experiences in any depth.

In his early childhood, Tony didn’t even know his father was Jewish. It wasn’t until Tony was an adult that his father’s full Holocaust experience was revealed, including a role he regretted until the day he died.

The story of Henry Bernard (formerly Bierzynski) is preserved in The Ghost Tattoo, a book that was four decades in the making for Tony Bernard,.

“When I was young, I knew very little of my father’s experiences in World War II,” says the doctor at Northern Beaches Hospital of his carefree childhood growing up with his sister Fiona and brother Nick.

“We just grew up in this really nice place near the beach and it was only as some of the stories would start to come out over the years that I’d realise he actually had a very different life to the one we lived in Australia.

“He would talk quite freely about his time in the concentration camps and there was this black and white photograph of his parents and he had this drawer in his wardrobe with his blue-striped pyjamas and his mother’s photo. But when we’d ask what happened he’d say ‘I don’t want to talk about that’.”

It wasn’t until Tony travelled to Poland with his father in 1979 – and three more times in 1985, 1997 and 2001 — that Henry’s full Holocaust experience was revealed.

Henry was in Warsaw when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. As a university medical student, he initially worked in a makeshift Red Cross hospital. But his heart was with his girlfriend Halina, 30km away in his hometown of Tomaszow and eventually he would go back there.

Tomaszow was in a Nazi-occupied area where one third of the population were Jewish. By 1941, the occupying Germans created a Jewish ghetto in the town, one of more than 100 throughout Poland, and young local men like Henry were recruited into the Jewish Police to enforce rules such as curfews.

It was a role Henry would regret, and be ashamed of, for the rest of his life – despite never mistreating anyone. He went on to spend time in three concentration camps: Blizyn, Auschwitz and Kaufering (a subcamp of Dachau).

“The Germans had this way of administering the Jewish population through the Jewish Council which they set up,” Tony explains.

“When they needed workers or when a curfew was imposed, it was regulated through the Jewish Police. I think Henry’s father put him into it because they were all putting their sons in there to keep it as an honest organisation.

“Dad was embarrassed to talk about it and he felt conflicted about it because he felt he had in the end been inadvertently helping the Nazis. It was something he was never proud of and he told me he regretted ever having anything to do with them.”

When Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning film Schindler’s List was released in 1993, it had a profound effect on Henry and was a turning point for a man who had hidden so much of his past for so long.

He went from a man who wanted to conceal his past, to one who wanted to reveal it.

“He was very moved by the movie and I remember he said to me ‘That was exactly what it was like’,” Tony recalls.

“He said ‘Some of the stuff in that movie happened to me, the shooting in the head when the gun keeps jamming and with the swallowing of the jewellery’.

“He was in his 70s … and I think he just wanted to get his story out there and on the record.”

Henry badgered his son to record his story straight on to a video and by 2006 they sat down in the Narrabeen home Tony had grown up in and made several three-to-four-hour recordings in which Henry revealed his entire Holocaust experience.

Tony would later turn these recordings into a manuscript that would form the foundation of his book.

Throughout these interviews, Henry revealed his deepest regret at being in the Jewish Police and his inability to save his mother, Theodora, from being deported to the Treblinka camp where she died – a moment that traumatised him until the day he died.

He revealed how he secretly married his girlfriend Halina in 1942 before they were sent to Blizyn and how, despite surviving that camp, she died of tuberculosis a few years later.

He also recalled a violent interrogation by the Gestapo and the weeks he was kept in a hole at Blizyn following his brother, Ignacy’s escape. And the torturous months he spent in Auschwitz in 1944.

Henry also spoke about his liberation by the Americans from the camp at Kaufering on April 27, 1945, his decision shortly afterwards to relocate to Australia where his Uncle Wolf was living and his struggle to form a happy marriage with his second wife, and Tony’s mother, Evelyn, in Narrabeen — a marriage that dissolved when Tony was still young.

And he spoke about his trip to Darmstadt in Germany in 1970 to give evidence against the violent former Nazi Georg Boettig, which ultimately convicted him.

“I’m sure the reason he went to such lengths for me to record his story was that he wanted the world to know what he had seen, in the Tomaszow ghetto in particular,” Tony says.

“This actually happened, these people existed, all those people died in those horrible ways. The fact he names (during the trial) all the people he saw killed, it’s like he’s saying: this happened to these individuals, these people were killed one by one and I saw it happen and, as a survivor, it’s my duty to tell the world and to remember them.”

Henry retired in 2002 at the age of 82. He died on September 20, 2016, aged 95. The man who drove his hearse to the chapel of the War Veterans Village overlooking Narrabeen Lake had been delivered by Henry at Mona Vale Hospital 40 years earlier.

His ashes are buried under a giant weeping fig tree in the backyard of his Narrabeen home.