Ghost town: Cousins fight to keep Bimbi alive to preserve its history

It lost its future to the railway and its young men to war. But Margaret Nowlan-Jones and a few like-minded locals could not let this tiny ghost town’s stories be forgotten.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

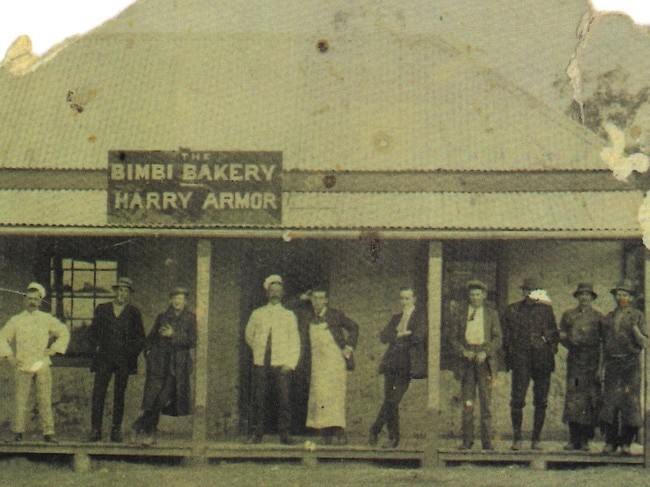

An avenue of peppertrees once welcomed visitors down the main street. The buildings lining its sides were the domain of friendly locals: Mr Smith, the aptly-named blacksmith, Mrs Sweeney at the Refreshment Rooms, Mr Morrow, the village teacher and Mrs Greig, the postmistress among them.

This was Bimbi in the early 1900s.

The close-knit community deep in the heart of central west NSW didn’t experience a boom from the discovery of gold or mines that brought up treasures from underground. Nor were they on a central route linking bigger towns.

But they were prosperous nonetheless, a small town built up by the sheer hard work of its farmers. A “town on the make” as one newspaper of the time put it.

There had been the promise of a railway to connect their little town to the Forbes Line. But in 1912 the decision was made for the railway to bypass Bimbi.

It was the first nail in the town’s coffin. The second nail came with World War I.

That cataclysm robbed Bimbi of one-third of its strong, single, young men.

Visit the town today and the tarred main road is empty, the stumps of the once proud peppertrees that were chopped down and one last building – the old post office – are all that remain.

This charming, single-storey timber and brick building has become a symbol of the promise of the forgotten town.

LAST BUILDING IN TOWN

Fifth-generation resident Margaret Nowlan-Jones – who bought the crumbling, boarded-up post office in 1986 with her cousin Annabel Nowlan – is determined not to let this last vestige of the town her ancestors farmed since the mid-1800s disappear.

“When I bought (the post office) in 1986 with Annabel for $2200, it was all boarded up and the picket fence was down in the long grass,” recalls Margaret, who now lives in Wagga almost two hours’ drive away.

“A drover had gone over it with his cattle and taken down the western wall and all the windows were shattered. Annabel’s father said at the time, ‘It’s the worst piece of real estate I have ever seen in my life!’ And he may have been right. But it was all that was left of Bimbi and we couldn’t see it just disappear.

“We had an open day in 1988 to celebrate Australia’s bicentenary and the restoration of the post office and I remember Mum saying, ‘Will anyone come?’ And I won’t lie, I had my doubts too.

“But around 500 people came – they started arriving at 7am. It was a great day, we had a whip-cracking competition, men on horseback pretending to be bushrangers, a bushrangers’ ball in the hall, a yarn (story) telling competition and big urns over the fire for tea and scones.

“It was exhausting but it was heartening to see how much interest there was still in Bimbi, that maybe it hadn’t been forgotten. Many of the people who came had connections to the village.

“One lady said she was the postmistress and another said her grandmother was a midwife there.

“It was like all these people had their stories to tell, but no one to pass them on to. A lot of people gave me old photos and I felt a sense of responsibility with them.”

That day the visiting population of Bimbi swelled to numbers nearing its heyday of 700. And that sense of responsibility grew into what has become an almost lifelong passion for Margaret who is determined to preserve the history of Bimbi and its people, including the First Nations people, the Wiradjuri, who helped her ancestors survive the inhospitable land they came to in the 1840s.

This year, on August 27, the town’s cenotaph will celebrate 100 years, an event Margaret hopes will again rally support for this once-proud town.

“With the centenary of our cenotaph this year, we have asked the council to please plant 28 trees in memory of the men who didn’t come back from the two world wars,” Margaret says.

“This will replace the 21 trees planted for our World War I heroes who never returned and which the council chopped down in 2004 with no warning, plus seven more lost from World War II.

“Those trees used to welcome you into Bimbi and we feel they should again because Bimbi has a proud history that is worth preserving at all costs.”

HISTORY OF BIMBI

Irish convict John Nowlan arrived in Sydney on New Year’s Eve 1830. He was assigned to Thomas Arkell, a former convict and superintendent of the land west of the Blue Mountains around Bathurst. Nowlan gained a conditional pardon in 1837 and that same year his wife, Mary, came out to the colony as a free settler.

Together with James Hanrahan, whose father Patrick accompanied William Wentworth on his crossing of the Blue Mountains in 1813, they settled in the Weddin Mountains overlooking the future town of Bimbi in 1842.

Family folklore tells the story that the Wiradjuri people assisted Nowlan, leading him to water holes in the mountains where they lived for several years. Hanrahan was killed in 1847 and Nowlan leased and later purchased the Hanrahan estate, Wentworth Gully Run, then a 15,000-acre (6070ha) property.

John and Mary had one son, John Nowlan Junior, who would first marry Catherine Markham and have five children, then Marion Grant and have eight children.

One of the eight children from the second marriage was Margaret’s grandfather and, as such, she grew up in a home her father built where the Wentworth Gully Run homestead once stood.

By the time Margaret was growing up there in the 1960s and 1970s, Bimbi was already a shadow of its former self with only the post office, saw mill, hall and Catholic and Anglican churches.

But she, her siblings and her cousins grew up hearing stories of how prosperous Bimbi had once been, a difficult scene for them to contemplate in the slowly-dying town. Seven Nowlan families – Margaret’s cousins – still farm the land in and around Bimbi.

“I’m a nurse, not a historian but after working on the post office restoration and discovering so much about Bimbi’s past, I enrolled in university for an advanced diploma in local and applied history by correspondence through Armidale,” Margaret says.

“We had to do an assignment on where we came from and I said to my lecturer, ‘I have a problem, where I come from, there’s nothing left, just a war memorial and cemetery’.

“And he told me I had to go and look at the names on the memorial. There were 76 names on it and two people came forward to help me research, including 94-year-old Bruce Robinson from Grenfell. His father, Roy Robinson, was at Gallipoli and his uncle, Reg Grimm, committed suicide shortly before Anzac Day 1932.

“Together we created a 200-page book called The Bimbi & District ANZACs.”

Their research uncovered many stories of bravery on the war front.

There’s Charles Herbert Napier, a single 24-year-old farmer from Bimbi who enlisted in World War I in August 1915 with his older brother John.

Charles fought in Pozieres from July 1916, a battle in northern France which is considered to this day as the scene of one of the most brutal military bombardments in history.

A brave Charles was invalided several times but kept returning to the front again and again and made it back home in January 1919. He married in 1923 and had five children.

But not all of Bimbi’s sons were as lucky.

Anthony Steel Caldwell, 24, left Australia in July 1916 to join the Royal Flying Corps in England as Australia did not yet have an Air Force. He was killed in a flying accident near Doncaster, England, and buried there with full military honours.

GHOST TOWN

Margaret has lobbied Weddin Shire Council many times over the past two decades, begging them to acknowledge Bimbi and stop it from completely dropping off the proverbial map.

Together with her cousins and the few concerned residents left in Bimbi, Margaret led a 17-year fight to get the peppertrees replanted, has requested simple services such as garbage bins and public toilets be installed and repeatedly begged for funding to help preserve the old town.

In October last year, the Bimbi Progress Group was formed – including Margaret’s husband John Jones, Sandra Holland, Christine and Barry Piper and their daughter Cailin – after the council told them they were unlikely to receive funding without one.

“I feel that the Bimbi community has been very much excluded from the Weddin Shire,” Margaret says.

“We are all very disappointed and angry at the way we have been treated by the council, we want to see a change. They even created a bird trail throughout the shire and left Bimbi off it, despite the fact Bimbi is the Aboriginal word for ‘place of many birds’ and my mother, Moyia, and I presented them with a list of more than 160 birds sighted in the Bimbi area. It’s an accumulation of a lot of things that has left us feeling abandoned and forgotten.”

Acting Weddin Shire general manager Jaymes Rath agrees the localities of Bimbi, Bumbaldry and Marsden are very much “shadows of their former selves” but denies this has anything to do with a lack of interest by the council.

He says in recent years Bimbi has received a comprehensive flood plain management study which is still underway, heritage funding for the post office restoration, approval of new street signage and approval of the Memorial Avenue of Trees, which was given the go-ahead in 2018 but still has not been assigned a planting date.

“I really hope we can have the trees planted before the centenary of the cenotaph in August,” Margaret says.

“It would be such an honour to the Bimbi men who gave their lives for Australia and a beautiful landmark for a town that should not be forgotten.”