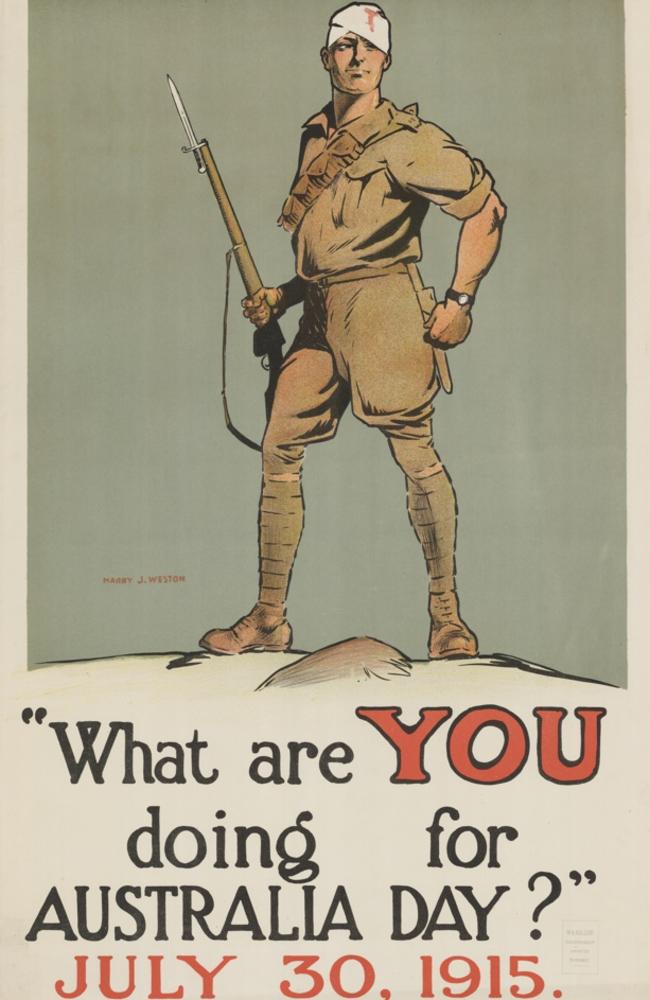

Australia Day started as a fundraiser on July 30, 1915 during WWI

A woman who created Australia Day as a fundraiser in midst of World War I started a popular tradition which benefited our soldiers on the battlefront.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The date July 30 is likely to mean nothing at all to you. It’s not a big event on our annual calendar of national celebrations, nor is it a religious day. But in 1915 it was the very first Australia Day.

Thanks to the efforts of Ellie Wharton-Kirke, a mother from Manly, the day marked a successful fundraising drive which benefited our soldiers on the war front. So successful in fact that it raised more than £1m between NSW and Victoria.

While this day has no association with the modern Australia Day, it was a day that, in the midst of World War I, highlighted the emotional strain felt by families at home.

“Ellie becomes the very public face of the physical and emotional toll World War I had on the homefront,” says Bart Ziino, a senior history lecturer at Deakin University who is working on a book about the Australian homefront during the devastating conflict.

“We mostly hear about what the soldiers went through, rightly so, but you rarely hear people talk about how awful it was for the families back home. These sons went away for an undefined time and families were left not knowing when they would be home or if they were safe.

“Ellie really embodied this mood and this is largely why Australia Day 1915 was such a success.”

Ellen “Ellie” Clements was born in Queensland in 1865 and married Samuel Wharton-Kirke in 1885. The couple settled in Dubbo where they had Hazel, Errol, Clement and Basil and then moved to Armidale where their youngest son, Hunter, was born.

In the early 1900s, the wealthy Catholic family moved to Manly and settled in a large home perched high on Cliff St.

In 1914, the Wharton-Kirkes’ eldest son Errol enlisted in the Army and was posted to New Guinea. The following year Basil and Hunter also enlisted and Clement joined the British forces leaving only Hazel at home.

Like many wealthy young women at this time, Hazel helped raise money for charitable groups, predominantly those sending milk and money for Belgian babies affected by the German invasion.

Ellie also wanted to contribute and wrote to a Sydney newspaper in January 1915 proposing “a day be set apart for the benefit of the wounded, and that it should be called Australia Day”.

The success of Belgian Day that May further inspired Ellie to hold an Australia Day fundraiser and July 30 was chosen.

With the help of other charitable groups, including the Red Cross, Australia Day was celebrated nationwide, but predominantly in NSW and Victoria.

Parades and celebrations were held in country towns and metropolitan suburbs along with sports days, fairs, street parties, concerts and banquets.

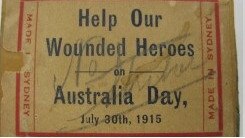

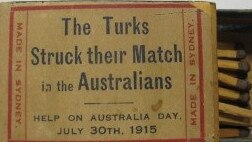

Martin Place in Sydney was transformed with booths selling everything from “embroideries and laces to potatoes and pickles” while ladies and children collected cash donations and sold patriotic badges, ribbons, handkerchiefs and matchboxes.

Shortly after, Ellie said in a letter to a local paper: “Now that Australians have responded so magnificently … I am confident if a consensus of the opinion of the people of Australia was taken, it would be to spend money on our soldiers immediately, not only the sick and wounded but to help our brave fellows from becoming sick and wounded.”

A month after that letter was published, Ellie’s son Basil was wounded at Gallipoli and invalided home. And in August 1916, Errol was killed at Pozieres in France.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

BIRTH OF RED CROSS AUSTRALIA

The Australian branch of the British Red Cross Society was formed in 1914 by Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, in response to World War I.

It grew rapidly, particularly in NSW where there were 88 city and 249 regional branches by the end of the year. As well as facilitating the donation of money and home comforts for soldiers on the front, the Australian branch also helped families gather details on dead soldiers and where they were buried.

Today, Australian Red Cross helps people find shelter, support, and loved ones, and responds to disasters.

JANUARY 26 OVER THE YEARS

From the early 1800s, January 26 was called Anniversary Day or Foundation Day and was mostly celebrated just in NSW.

Other states held their own annual celebration on different days, for example, Western Australia had Foundation Day on June 1.

It wasn’t until 1935 that a national event called Australia Day was held on January 26, and it became a national public holiday in 1994.

But each year the debate over using January 26 as a national day of celebration, often referred to as Invasion Day, builds, with pressure to find a new date.

Our first graveyards reveal Sydney’s history of death

Convicts were laid alongside free settlers and not far from military families, their deaths included murder, tragic accidents, disease and execution.

The 2361 men, women and children interred in the Old Sydney Burial Ground – Australia’s first official post-European cemetery – have over the years been named and their stories unearthed by researchers using diaries, newspaper articles and government records.

Among them is young convict William Meredith, buried in October 1793, who was killed by a lightning strike when he and fellow convict Dennis Reardon were chopping wood. When the storm hit, they sheltered under a tree and were found the next day huddled together with a dog, all three of them dead. The men were buried together in the one grave.

There’s also freeman John Miller, aged 46 and buried in October 1816, who was murdered at his Petersham farm. And there’s Francis Morgan, buried in November 1796 after he was executed for robbing the public stores.

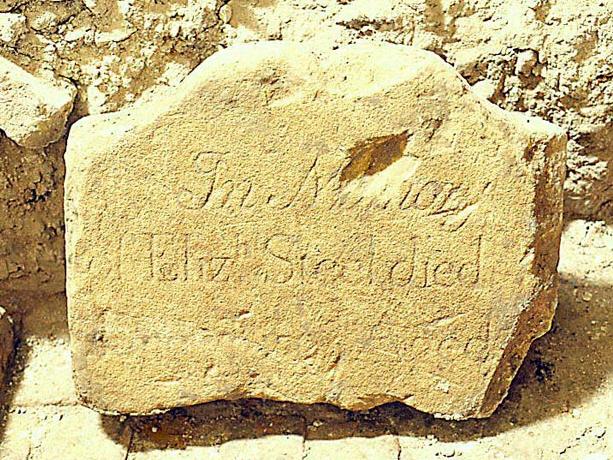

A 1991 investigation of the site, conducted before stormwater pipes could be laid in the basement of Town Hall, revealed a partial sandstone headstone.

You can just make out the words “In Memory” and “Eliz. Steel”. We now know this was the final burial place of convict Elizabeth Steel, transported to NSW on the Lady Juliana in May 1787 for seven years for stealing a silver watch from George Childs, a customer at the public house in London where she worked as a prostitute.

The Old Bailey court transcripts at the time of her arrest describe her as being “mute by visitation of God” – in other words, deaf – and on arrival in Sydney she was transferred to Norfolk Island.

There, she married fellow convict Irishman James Mackey and they set about farming a 10-acre parcel of land until their sentences expired.

Sadly, just 10 months after returning to Sydney a free woman, Elizabeth died and was buried at the Old Sydney Burial Ground in 1795.

The list of those buried under the ground at Town Hall also include many babies, infants and children as infant mortality in the early colony was high.

There’s little Jane Morley, who was just two months old when she died in a fire in July 1801. The headstone reveals a tragic poem: “My parents’ loss is my eternal gain, here I rest free from worldly pain. The fire snatched my life away as I was at harmless play.”

Five-year-old Letitia O’Neal was buried at the grounds in March 1806 after a coroner’s inquest found she died after she fell into a well at the rear of her father’s house in The Rocks.

Meanwhile, the headstone of three-year-old Mary Skinner carries a dire warning: “Be careful how you live, death does not always warning give. As you are, once was I, but as I am so must you. Be prepared yourself to follow me.”

When it was established in 1792, the Old Sydney Burial Ground was far enough away from the centre of town to be considered on the outskirts. But as the population grew the Old Sydney Burial Ground became an eyesore and it was closed and abandoned in 1819.

It wasn’t until 1869 that the land was repurposed as the site for Sydney Town Hall and the process of exhuming the bodies and graves began.

Subsequent improvements and expansions to Town Hall over the next 150-odd years – which included extensive archaeological investigations in 1974, 1991, 2003 and 2008 – revealed human remains, coffins and burial paraphernalia.

“The 2008 excavations at the Old Sydney Burial Ground provided a rare opportunity to investigate non-Aboriginal burials in Australia dating from the early 19th century,” the report by archaeological and heritage company Casey and Lowe stated.

“The results take us back to a time when a premature death was more likely, Sydney far smaller, and the major burial place was within easy walking distance of most of the town.”

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

DEVONSHIRE STREET CEMETERY

On the site of the present-day Central railway station, this burial ground, also known as Brickfield Cemetery and Sandhills Cemetery, was consecrated in 1820 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie and became Sydney’s second official burial ground.

But by 1860 it was full and by 1867 it had closed. As with the Old Sydney Burial Ground, graves at the Devonshire Street Cemetery were exhumed from 1901 to make way for Central station.

Some notable people buried here include bushranger John Dunn, architect James Hume, theatre director Barnett Levey, and merchant and shipowner Mary Reibey.

DEATH IN THE EARLY COLONY

Before the Old Sydney Burial Ground was established in 1792, people in the new colony were buried close to The Rocks, notably at Dawes Point, near George St around Campbell’s Wharf and at Clarence St between Margaret and Erskine streets.

There was another cemetery in Parramatta, St John’s Church of England Cemetery, established in 1790.

It remains Sydney’s earliest undisturbed colonial cemetery, according to the Dictionary of Sydney.

Life expectancy in the early colony was not great with adults expected to live only into their 30s. Infectious disease and accidents were main causes of death.

‘Tinder of the day’: Ad looking for love led to shooting death

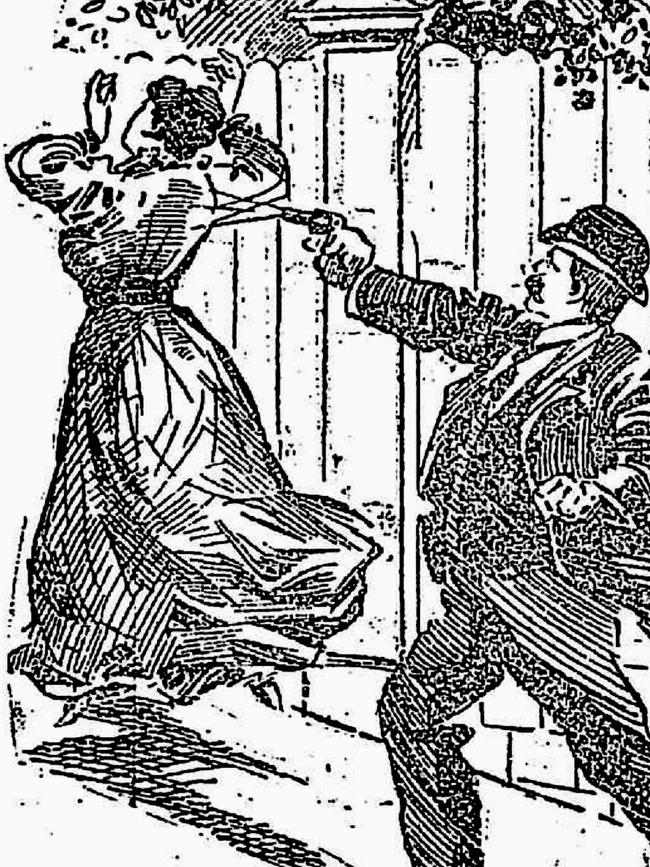

The newspaper headlines of the day marked Maria Flynn as a “vile, cruel, calculating adventuress”. And, despite the fact she was murdered by her lover in the street in 1899, the story that was revealed in the subsequent court trial proved she was also guilty of wrongdoing.

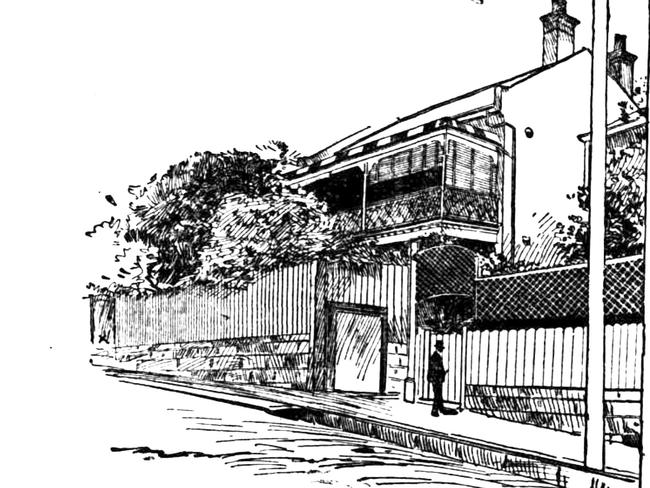

Flynn was an Irish governess employed in the home of wealthy wool merchant FJ Gow. He lived in a grand Victorian mansion on Cameron St, Edgecliff, called Portobello, with his wife and five children when Flynn came to them with sterling references.

On the morning of February 2, 1899, Flynn was heard squabbling with a man at the front door before slamming the door shut.

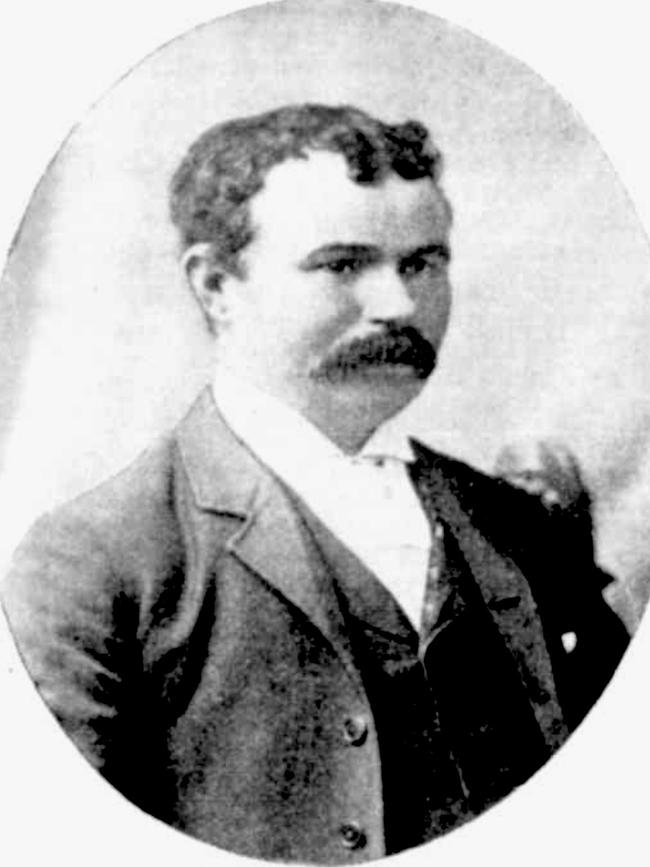

Undeterred, the man, later identified as Michael Henry Kelly, burst through the tradesman’s entrance and pointed a pistol at Flynn. Kelly chased the governess through the house, shooting at her and missing three times, and out the back door into the yard where he shot two bullets into her back.

She collapsed near the gate leading onto Cameron St; Kelly stepped over her body into the middle of the street and shot himself in the chest, collapsing on the spot.

Flynn died later in the day and was attended by a Catholic priest, who administered the last rites, and a doctor.

Kelly survived the attempted suicide and was taken to St Vincent’s Hospital where he made a full recovery in a room under police guard.

“Initially the newspaper reports are all in her favour and paint her as the victim,” says murder historian Max Burns-McRuvie of Journey Walks, who has researched this story for his upcoming series of talks called Cocktails And Crime Stories to run at Since I Left You bar in the Sydney CBD on the first Wednesday of the month from February 2.

“There’s a lot of speculation in the newspapers but when Kelly recovers enough, he tells a ridiculous story which began the year before and which would turn the whole story on its head.”

In July 1898, Kelly was working on the Clarence River in northern NSW when he saw an advertisement in the matrimonial column of a local country paper. A governess living in Sydney was seeking a husband and asked for gentlemen to reply with information and a photo.

“It’s like the Tinder of the day,” says Burns-McRuvie.

“Kelly answers the ad and sends information about his background, telling the lady he has money. She responds that his letter is the best one she has received and asks him to come to Sydney to court her.

“They date for a few months, he spends a fortune staying in a Sydney hotel, and she tells him she’s waiting on money from a court settlement. In the meantime, she borrows quite a lot of money from him.”

Kelly proposes and gives her an expensive engagement ring. But just five months after they met, Kelly received a letter telling him the court settlement had become complicated and Flynn would be away for several weeks.

While he waited for her to return, he saw another ad in the matrimonial column with a different name but otherwise very similar to the one he answered and he began to spy on her, seeing her catch a tram to Double Bay and another to a pawnbrokers in Liverpool St.

He quickly realised she was not away, but living in Sydney still.

Kelly confronted her and demanded she return the money he loaned her. And after a few failed meetings, he arrived at Portobello and threatened to expose her to her employers.

This was the argument that was overheard at the door on the day of the shooting.

Despite the initial articles in her favour, The Truth newspaper investigated Flynn further and discovered she was not Maria Flynn, but Mrs Carey, she was married to a professional conman and together they had duped several men.

The jury, swayed by this information, found Kelly guilty of manslaughter and he was sentenced to seven years in jail.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

A TALE OF TWO CRIMES

The day after a man by the name of Briggs was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol for shooting his girlfriend and her grandmother when the former dumped him, Kelly was sentenced to seven years (five with good behaviour) for a similar crime.

The similarity was too much for one newspaper columnist, who claimed justice had been blind in the case of Kelly.

“There may be differences between the two cases … but the line of demarcation between the guilt of Kelly and the guilt of Briggs is too fine to justify one man getting five years and the other all eternity.”

THE LONELY HEARTS CLUB

With such care taken to construct Tinder profiles these days, spare a thought for the lonely hearts ads of past centuries.

While advertisements designed to find the perfect partner appeared in England as early as 1695, they were particularly popular in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In 1750, one man advertised for a lady with “good teeth, soft lips, sweet breath, with eyes no matter what colour so they are but expressive, of a healthy complexion, rather inclined to fair than brown, neat in her person, her bosom full, plump, firm and white …”

How NSW ambulance service evolved from 1895

On a cool September day in 1922 an ambulance was called to a property in Como near the railway bridge in Sydney’s south. A workman had been injured when a machine fell on him, shattering his leg.

And so began another of the often-hazardous treks ambulance officers in the first half of the 20th century faced to reach their patients and take them safely to a hospital.

To reach the injured man in Como, the ambulance had to cross the Georges River on the Lugarno ferry, then proceed along a bush track, where the ambulance was bogged twice. The return journey was even more challenging, and the vehicle was bogged several more times with the patient inside.

“Progress was at the rate of about one mile an hour,” says John MacRitchie, local studies librarian at Georges River Council, who has researched the early establishment of the St George District ambulance service.

“The ambulance men had to pull down branches and find stones to free the vehicle from patches of mud, and were plastered with mud themselves by the time they finally got the badly injured man to hospital.”

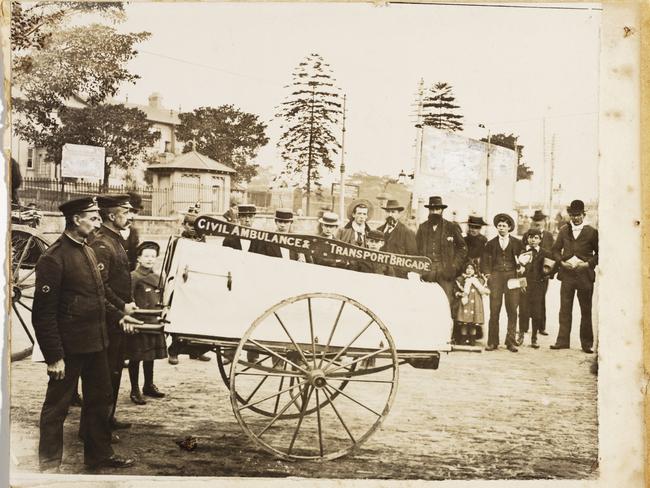

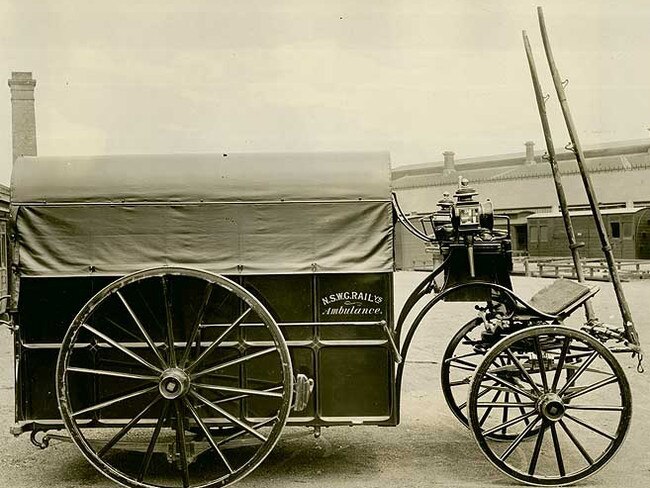

The first ambulance service in NSW was known as the Civil Ambulance and Transport Brigade and it operated from April 1, 1895.

They famously ran the service out of a borrowed police station at Railway Square in Sydney with a staff of two. Initially patients were transported on handheld stretchers and hand-litters but by 1899 the service had its first horse-drawn ambulance.

In 1901 stations were established at St Peters, Woollahra, Balmain, Rockdale and Circular Quay and early rescue reports in the local newspapers highlighted the difficulty in transporting patients.

While the first ambulance vehicle was introduced in Sydney in 1912, thanks to donations from the public, St George was still using hand-litters and stretchers on wheels as late as 1917.

“On one occasion in 1917, the hand-litter was called to Bankstown to collect a patient,” MacRitchie says.

“The time elapsing before she could get to hospital meant that she died on the way. On another occasion, with an assistant, the ambulanceman had to wheel the litter to a fire at Tom Uglys Point some seven miles away and in heavy rain.

“When they arrived, they found there was no fire and no casualty – it was a false alarm, or a hoax. Imagine how exhausted the men must have been.”

The Ambulance Service annual general meeting reported in 1921 they had seven motor vehicles operating in NSW, which had grown to 11 vehicles by 1925.

They also reported they had received 193,000 calls for help since their formation in 1895 and their crews had travelled more than 956,000 miles to attend to sick and injured patients.

Inaccessibility did not stop the ambulance officers once they received a call, as MacRitchie found in an article from October 1923.

“An old man collapsed at an almost inaccessible property at Gungah Bay,” MacRitchie discovered through his research.

“The ambulance officers had to take a boat from Como and were rowed across to the scene of the accident by Mr Bryant, the boatshed proprietor, who also rowed them back to Como with the patient, who was then taken on a train to Hurstville.”

Another issue faced by these early suburban stations was a lack of funding for sufficient staff. One case MacRitchie discovered in 1924 highlighted this frustrating situation.

“In June 1924, a man fell under a train at Hurstville Station and his legs subsequently required amputation at St George Hospital,” MacRitchie says.

“However no ambulance was readily available as it was transporting another patient to the Coast Hospital. So, the patient was taken by train to Kogarah and transferred by stretcher to the hospital, with considerable delay.

“The Superintendent stated there were two two-man teams available – one covering the night shift, the other the day shift – but there was no one available to man the second ambulance, which sat idle.”

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

HEELS FOR FIRST FEMALE PARAMEDIC

When Lee Clout joined the Wagga Wagga station of NSW Ambulance in May 1979, her uniform included high heels, which the then-20 year old quickly swapped for boots.

As the first female paramedic with NSW Ambulance, she went on to pioneer a trail for women, who today make up more than 40 per cent of the service and account for almost half of the senior leadership roles.

“I always wanted to be a paramedic and I had the skills to do the job,” she said in a NSW Ambulance commemorative booklet in 2019.

“It was as simple as that.”

A CENTURY OF FIRSTS

The NSW Government Railway Ambulance and First Aid Corps was set up by the railway commissioner in 1885 but a decade later, the Civil Ambulance and Transport Brigade was formed.

In 1899, the first horse drawn ambulance was added to the service and bicycle ambulances in 1904. The first vehicle ambulances came in 1912 and radio controlled vehicles in 1937.

A rescue service was introduced in 1941 and a training school in 1961. By 1967, the air ambulance was established, intensive care vehicles in 1976, helicopter ambulances in 1983 and motorcycle ambulances in 1993.