NSW history: Sisters murdered in Dulwich Hill lolly shop in 1928

A much-loved confectionary store was the scene of one of the most sensational murder mysteries of 1920s Sydney.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sydney lawyer Danny Eid swears he has never heard strange noises working late into the night at his law firm in Dulwich Hill. He was interested to hear, however, that on a cold winter night in 1928 a double murder took place in his building at 522 Marrickville Rd.

The beautiful Victorian shopfront where Esther Vaughan ran her confectionary store with her sister Sarah Falvey long ago burnt down and was rebuilt, and several businesses have since been run from the premises, including a refrigerator and washing machine repair shop, real estate agency and travel agency.

But the irony isn’t lost on Eid that a double murder which became one of Sydney’s most sensational court cases of the 1920s occurred on the very spot where he runs his criminal law firm today.

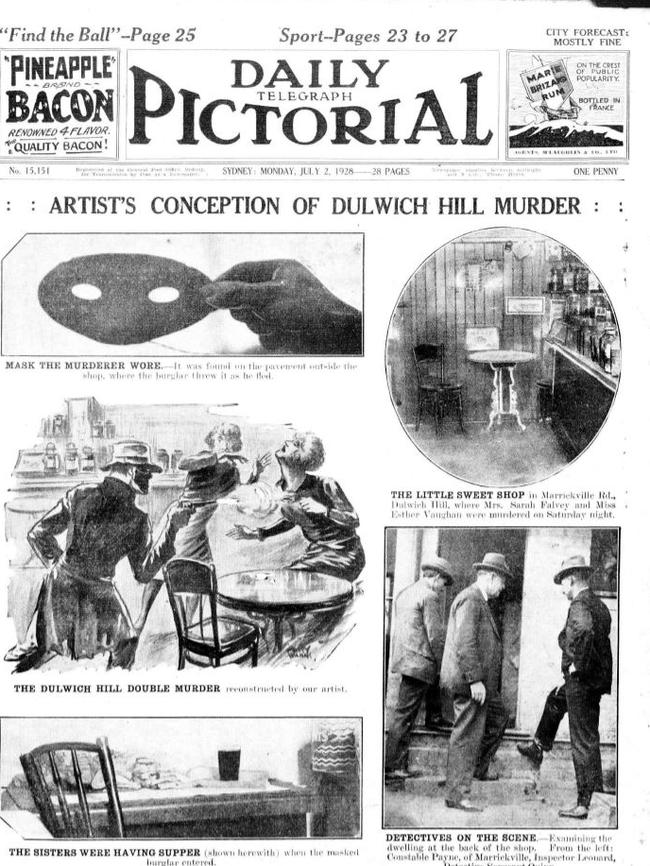

Vaughan, 55, was tallying up the day’s takings at the counter of her lolly shop late on the evening of June 30, 1928 while her sister ate a late dinner of sandwiches at a table nearby. The unmarried Vaughan had run the shop for nearly 20 years; her sister, recently widowed, had joined her to help. The shop was a local institution and on this night they were staying open late to get the after-show crowd leaving a nearby cinema.

At about 10.15pm shots were heard from the shop and both ladies were found dead in the premises.

Burglary was the obvious motive, but £55 was later found in the building and the money Vaughan had been counting that evening was still on the counter.

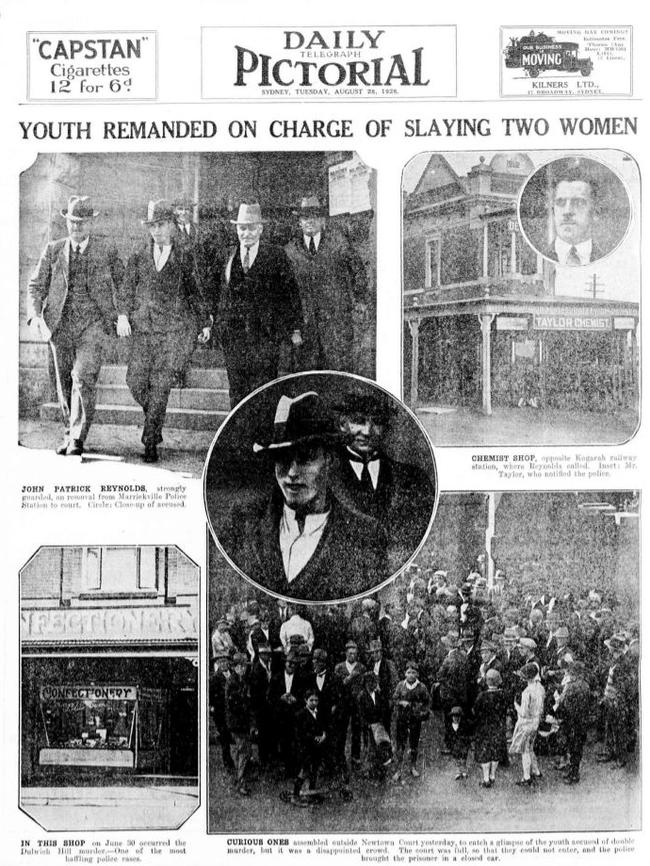

A police investigation revealed a masked intruder had fled the scene shortly after the shots were fired and a young local man by the name of John Patrick Reynolds was charged with the murders.

The 18-year-old had a reputation for working scams on local businesses for small amounts of money, a few pounds here and there, and he was identified by a witness as the man seen leaving the shop that evening.

Historian Michael Adams, who researched this case for his podcast Forgotten Australia, says the media coverage of the investigation and court case was sensational.

“There was fantastic newspaper coverage competing for headlines,” he says.

“Papers like The Daily Telegraph Pictorial ran photos but also artist’s impression of the murder scene and the Truth newspaper even came up with a convoluted theory that the killer may have been a woman, with absolutely no basis whatsoever, just to sell a few more papers.”

Reynolds was born in 1910 in Albury and moved to Sydney, where his father lived, in 1927.

On the journey up to Sydney he stole a man’s clothes and subsequently spent two months in prison. But that didn’t deter him.

On arriving in Sydney he started working his scam around the inner west, dressing nicely or in a uniform and asking businesses to lend him small sums as he’d fallen short. There were ultimately enough cases to charge him with 40 counts relating to this scam.

Police quickly built up a theory he had tried to defraud the sisters, who were well known in the community for helping those in need, and it had gone wrong.

Reynolds’ defence was that he wasn’t in Sydney on the night, that he didn’t know how to ride a motorcycle, which the masked man had been seen leaving on, and that he didn’t own a gun. All these claims were later refuted by witnesses.

In the end he gave three different accounts of where he was on the night in question. But he was acquitted after the witness who identified him leaving the lolly shop that night admitted he couldn’t be absolutely certain the man was Reynolds after all.

Reynolds, who maintained his innocence throughout the trial at Newtown Court, showed no remorse and was often caught smiling and waving at acquaintances in the audience.

He lived into his late 70s just a two-minute walk from the lolly shop.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

LIFE OF CRIME OR COINCIDENCE

Just 15 years after he faced trial for the lolly shop murders, John Patrick Reynolds turned up at the scene of another murder of a middle-aged widow, this time in Perth.

On June 26, 1943, a 53-year-old woman was raped and bludgeoned in a park.

Reynolds, who was working as a military police officer, was first on the scene, but strangely, 30 minutes after the woman’s screams were heard.

Reynolds pointed the finger at Norman Lawrence, an intoxicated man who had been near the scene and who Reynolds claimed had confessed to him. Lawrence was arrested and sentenced to life in prison.

CITY’S YEAR OF BLOODY MURDERS

In 1932 – while the city grappled with the worsening Depression and celebrated the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge – Sydney experienced what has been referred to as the “red year”.

Michael Adams chronicles the spate of murders from that year over 14 episodes in his podcast, Forgotten Australia.

He recounts the story of two sweethearts killed in a deserted bushland; the Hammer Horror in which a man was bashed to death in the bedroom of an eastern suburbs mansion; the shooting death of a man by his lover on a Sydney street; the murder of two police constables and more.

Historical drama of Sydney’s Theatre Royal

The anonymous caller spoke just three words down the phone line at Sydney Central Police Headquarters: “Theatre Royal 10pm.”

A who’s who of Australian politics, business and the theatre world had gathered for opening night of the musical Cats at the Theatre Royal on a cold July night in 1985.

Shortly after the call to police, then-prime minister Bob Hawke was cooling his heels by the side of King St along with then-treasurer Paul Keating, Cats composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and some of the theatre world’s biggest names including Barry Humphries, Reg Livermore and Sir Robert Helpmann.

Also in the crowd that evening was Tim McFarlane, executive chairman of Trafalgar Entertainment, who have a long lease on the Theatre Royal.

“All of a sudden everyone was evacuated, we found out afterwards there had been a bomb scare,” McFarlane recalls of the night.

“We were all moved into the retail areas of 25 Martin Place (then the MLC Centre). Andrew Lloyd Webber was there, Bob Hawke, all having to wait with the rest of the audience.

“But the show absolutely went on after the interval. And the production was a huge success.”

Cats was the first of three big musicals that revived the Theatre Royal during the 1980s and 1990s, running for two years from 1985 to 1987.

It was followed by Les Miserables from 1987 to 1988 and then Phantom Of The Opera from 1993 to 1996, which at three years, became the longest running production at the theatre.

And next month the Theatre Royal will enter a new era as it reopens after an almost five-year renovation, a process prolonged by the Covid pandemic.

Few people would know that the modernist Theatre Royal, designed by architect Harry Seidler, which opened on January 23, 1976, on King St has a history which spans almost to the earliest days of the colony.

The first time Sydney heard the name Theatre Royal was in October 1833, when entrepreneur Barnett Levey leased a theatre on George St, on the site where Dymocks is today, and called it Theatre Royal.

On Boxing Day that year the first performance of Shakespeare was held on Australian soil, with the production of Richard III.

Levey died in 1837 and the theatre burned to the ground two years later. A new Theatre Royal was built in 1875 on Castlereagh St, the same spot it exists today.

It opened on December 11 decorated in white, gold and grey, with a blue ceiling that contained twinkling stars, a big glass chandelier and red velvet chairs.

The direction for the Theatre Royal throughout much of the late 19th century and early 20th century was dominated by American impresario James Cassius Williamson, or JC as he was known, who arrived in Sydney with his wife Maggie Moore and the rights to Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore in 1878.

Over the years, together with a group of commercial theatre entrepreneurs, Williamson was responsible for the likes of soprano Nellie Melba, actress and singer, Nellie Stewart, and American actress Sarah Bernhardt performing at the Theatre Royal.

The last performance was held there on April 29, 1972, before the theatre closed, a new one to be incorporated into a planned development of the MLC Centre.

The theatre space was turned 90-degrees, giving it a new entry on King St and a capacity of 1157 seated over two fan-shaped levels.

During recent renovations, McFarlane says bits of the set from the Phantom days were discovered, including decorative plaster and a steel beam from which the grand chandelier hung, turning the theatre into Paris’s Palais Garnier Opera House for the three years of the Phantom’s run.

“You cannot keep this theatre down,” McFarlane says.

“The work that has been done now is really putting it back to a first-class theatre but with flourishes by Seidler which will be more prominent as the facade on King St is all glass, allowing you to see right into the foyer.

“It’s back and better than ever.”

Sydney theatre lovers can judge for themselves when the curtain goes up on award-winning musical Jagged Little Pill on December 2.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

THE PAWFECT MUSICAL

One of the most successful musicals ever, Cats was composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber, who put the poems of TS Eliot’s 1939 collection of Old Possum’s Book Of Practical Cats to music over four years.

The result was a smash hit that opened at West End’s New London Theatre in 1981 and ran for 21 years, and Broadway’s Winter Garden Theatre in New York in 1982 and ran for 18 years.

It tells the story of the Jellicle cats, who come together on one night each year to choose one cat to be reborn and ascend to the Heaviside Layer.

JC WILLIAMSON MAKES HIS MARK

The US actor and comedian was born James Cassius Williamson in Pennsylvania in 1844. He worked predominantly in New York and San Francisco where he met and married Maggie Moore, a fellow actor and comedian, in 1872.

The pair travelled to Australia often, bringing with them the rights to several Gilbert and Sullivan operas.

In 1881 Williamson acquired a lease for the Theatre Royal in Sydney and, in a partnership with Arthur Garner and George Musgrove, heralded a successful era for the theatre.

Williamson moved to Europe in 1908 and died in 1913, leaving behind the largest theatrical firm in the world.

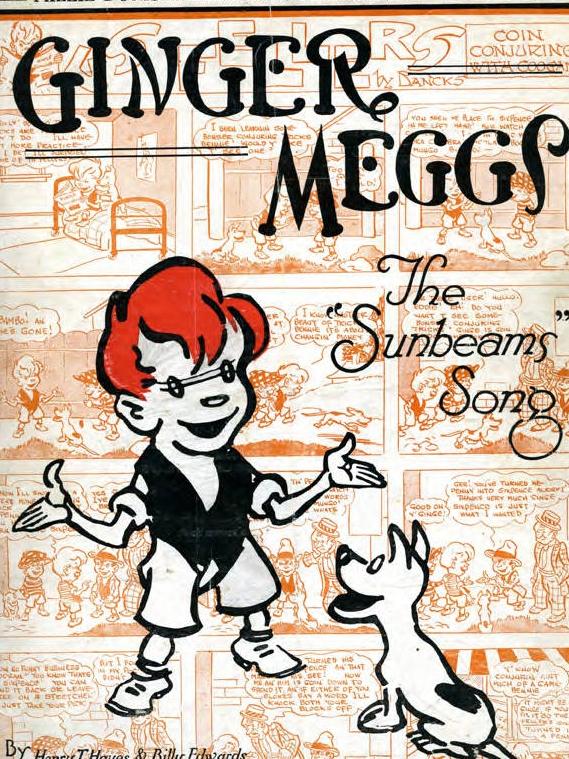

Ginger Meggs comic character’s Hornsby connection

Sydney was introduced to Ginger Meggs on November 13, 1921 – 100 years ago to the day.

Actually, that’s not quite correct. On that date, it was the mischievous red-headed boy Ginger Smith we first met. It wasn’t until the following year that his creator, cartoonist James “Jimmy” Bancks, changed his name to Ginger Meggs and so was born Australia’s longest running comic strip.

It was often mistakenly presumed this larrikin boy, who often got into fights and trouble at school, was an inner city dweller, but he was in fact based on Bancks’ childhood friend Charles Somerville with whom he grew up in suburban Hornsby, far from the gritty city laneways that are often associated with the famous cartoon.

To those on the upper north shore, Ginger Meggs is recognised as “Hornsby’s son” and in 1997 Hornsby Shire Council renamed the park in Valley Rd that Bancks played in as a boy in his honour – Ginger Meggs Park.

Bancks was born in the inner west suburb of Enmore in 1889 to John and Margaret Bancks. His father was a railway cleaner and when Jimmy was three, the family moved to a railway cottage in Hornsby where they would stay until 1910.

The Hornsby Bancks grew up in was a far cry from the bustling suburb it is today, then populated mostly by orchard growers and dotted with agricultural holdings.

The railway station around which the suburb would expand was only opened six years before the family moved to the area.

Still, it was this semi-rural suburban environment that inspired the adventures of the mischievous Ginger Meggs.

State Library of NSW curator Margot Riley says the comic strip was very much a product of Bancks’ Hornsby childhood.

“Although Jimmy and Charlie both came from working-class families, where money was tight, the kids ran wild and free among the trees and creeks, paddocks and orchards,” Riley says.

“Bancks recalled it as an unremarkable childhood but highly enjoyable, with all the local delights of cricket, football and swimming holes. In one of his later Meggs strips, Bancks directly acknowledged his Hornsby roots, paying special tribute to his old friend Charlie.”

In the comic strip Ginger Meggs greets his pal by saying: “Well, if it isn’t my best friend and greatest mate, Charlie. Well Charl, it’s a great treat to meet a fine friend, yes a fine friend like yourself Charl. Always ready to do a friend a good turn.”

Somerville wasn’t the only one of Bancks’ Hornsby friends to make an appearance in the famous cartoon. He also wrote about his pal George Lumby.

“Eh Ginge, did you hear about young George Lumby?” he writes in one story.

“He’s in bed with the mumps and can’t go to school for three weeks.”

In another scene he writes about Ginger Meggs stealing fruit from the Higgins and Foster Orchards, which were local Hornsby properties.

Bancks’ first drawings were published in 1914 when he was 25 and working as a clerk and a lift driver.

In 1921 he drew and wrote the comic strip Us Fellers and drew in the character of Ginger Smith. This naughty little boy must have been well received because the following year he had changed his surname to Meggs and given him his own comic strip.

In 1932 Bancks tried to explain why he thought Ginger Meggs was so popular; the comic strip was syndicated in just about every country in the British Commonwealth and in America.

“I have tried to make Ginger a real boy, human, natural and for the most part worthy of sympathy and goodwill,” he wrote in an annual compendium of the comic strip.

“Undoubtedly his outstanding characteristic is a marked inability to avoid trouble, but that does not bother him.

“Bad luck may dog his footsteps, fights may be lost and his well-laid plans go wrong, but always, he comes up smiling.

“His is an incurable optimism.”

Bancks died suddenly at his Point Piper home in 1952. He was 63.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

CHARLES TAKES CHARGE

Long after Charles Somerville and Jimmy Bancks kicked around together on the streets of Hornsby, Somerville would go on to become a businessman and a Hornsby Shire councillor.

The Somerville family opened a produce store on Jersey St in 1902 and Charles would take over the store for a period after his father James died.

The same year the Ginger Meggs character was born in 1921, Charles became a Hornsby councillor and he would go on to hold the office of mayor twice between 1936 and 1953.

He died in Hornsby in 1967.

GINGER’S AMAZING CENTURY

Starting in mid-December, the State Library’s AMAZE Gallery will pay tribute to 100 years of Ginger Meggs as part of its new summer holiday display.

On show will be Australia’s first colour comic supplement, which launched the character of Ginger in 1921, alongside original artworks and vintage newsprint strips by all five cartoonists who have drawn the character — Ron Vivian, Lloyd Piper, James Kemsley and Jason Chatfield — each artist enabling Ginger to move with the times and ensure “Australia’s favourite boy” stays relevant.

1919 Sydney murder of gay Englishman Hugo Tuck

It was a murder so unusual and so salacious for the time that the newspapers didn’t know how to report it, and the police detectives didn’t know how to talk about it.

And for many decades afterwards it was referred to as “the most notable (case) in the police annals of this country”.

It was the 1919 murder of English gentleman Hugo Tuck, who was bludgeoned to death in his luxury apartment on Elizabeth St overlooking Hyde Park.

Tuck was in his 50s when he arrived in Sydney from London in 1915. He was a “remittance man”, meaning his wealthy family had sent him away to Australia with enough money to live comfortably but with the promise never to return to England.

He took up residence at 181A Elizabeth St in a building that was constructed in 1908 and was occupied by one of the very first car showrooms in Sydney on the bottom floor with residential chambers on the upper floor.

The six residential apartments were looked after by Mrs Fitzpatrick, who would bring her lodgers breakfast each morning.

Tuck lived here under the name of Albert Spencer, or “Bertie” to his friends, and was known as a wealthy but private society man who liked to attend the theatre and eat in good restaurants.

On the morning of April 12, 1919, Mrs Fitzpatrick took up Tuck’s breakfast and found a “tall, delicate youth” by the name of William Doyle visiting Tuck.

He’d been there various times, Mrs Fitzpatrick recognised him as a “hotel useful”, or a boy who ran errands.

Later that morning a maid of the residential chambers noticed water gushing from Tuck’s apartment and on entering found a tap left on.

In a spare room she found Tuck, face down in a pool of blood. The back of his head had been battered in, but he was still alive.

Tuck was rushed to Sydney Hospital, but he died 30 minutes later. Police very quickly ruled his death a homicide.

In his apartment they found a number of interesting items, including letters in a chest, some from friends back home in England, and others that were described as being “ridiculously affectionate and romantic” from other men.

They also found on his person three diamond rings worth about $3000 in today’s money and, in another chest, more diamonds, cash and gold to the value of about $40,000 which led to Tuck being labelled “the Diamond King” in the media.

But when it came to reporting the details, both the media and the police were at odds to describe what was obviously a homosexual lifestyle.

“The newspapers spoke of him as being ‘a man of unnatural practices’ and a ‘degenerate of filthy character’, never once using the words sex or homosexual but alluding to it in every other way,” says historian Max Burns-McRuvie, who has researched this story for his upcoming Murders, Mysteries And Margaritas event at Since I Left You bar on Kent St on November 24.

The investigation soon led detectives to Doyle, 17, who initially denied any involvement but later confessed all.

At the June 6 trial Doyle claimed he hit Tuck in self defence after Tuck attempted to have his way with him, his defence lawyer painting Tuck as an indecent man. The jury found Doyle not guilty.

“The case was so sensational that ‘tuck’ became a codeword for homosexual behaviour for years later,” Burns-McRuvie says.

“And despite the vicious way Tuck was presented in the media and by police, he was only ever described by people who knew him as the kindest man with a sweet nature, not at all the aggressive type that would attack a young man.”

A year later Doyle was arrested for burglary and some questioned whether the jury had been too quick to pronounce him not guilty.

Tuck left an estate valued at $250,000 to two men in London who were not related to him.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

BLACK SHEEP OF THE GREETING CARD FAMILY

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Tuck was as synonymous with greeting cards as Hallmark is today.

Raphael Tuck started his company in 1866 selling printed art including lithographs in a little shop in Union St, London. He brought three of his four sons into the business – Herman, Adolph and Gustave – while Hugo was banished to Australia.

The company would go on to sell a wide range of greeting cards and postcards, including the first Christmas cards, the irony being the Tuck family was Jewish.

When Hugo Tuck was murdered while in exile from his family, they simply acknowledged the death by saying he died “after a short illness in Sydney”.

LONG ROAD FOR SAME SEX LAWS

When the First Fleet landed in Sydney in 1788, it brought with it the laws of England. And until 1994 sexual conduct between males was illegal.

Until 1899 it was a crime punishable by death, and thereafter life in prison. The rise of same sex rights in the late 1960s pushed for political and social change.

In 1975, South Australia became the first state to legalise sex between two consenting males. Tasmania became the last Australian state to do so, as late as 1997.

In December 2017, the Marriage Act of 1961 was amended to allow same sex marriage in Australia.