‘So, I’m mildly freaking out,” Margaret Lawson wrote from St Andrew’s Hospital where, having not been able to get an appointment with a GP, she’d gone to ask for a CT scan for a lingering headache.

The successful public relations firm owner had recently returned from a trip to the US and was worried about blood clots. She’d felt a little silly while talking to a triage nurse. Would they think her a hypochondriac?

“Oh gosh,” Lawson’s friend and work colleague, Jackelyn Cross, wrote back. “What?”

“My CT scan showed ‘abnormal areas’ on my brain … I’m googling like crazy. Which does not help,” Lawson texted.

“Yeah,” Cross replied. “Dr Google might not ease the panic.”

The conversation between the two women continued. One holding down the fort in the office, the other alone in a hospital waiting room. The CT scan had been followed by an MRI. Then a chest X-ray. Hospital staff had asked her repeatedly if she’d ever been a smoker. She hadn’t.

“That f--king cough you’ve had,” Cross wrote. “That just never f--king left you.”

“I don’t have a cough,” Lawson wrote back. “Do I?”

A doctor approached. Asked if she was there alone. She said she was. The doctor asked if there was someone she could call. “Tell me,” Lawson said. Then, another text to her colleague: “They just came in and told me it’s cancer. They think lung. And maybe brain.”

Cross’s reply was short. The only words needed between friends: “On my way.”

On June 3, the life Lawson knew changed forever. It was the day she, at age 45, was confronted by her mortality. “It’s kind of like waking up one morning and discovering you’re a steerage passenger on the Titanic,” she says.

“You know there’s an iceberg out there and there’s nothing you can do about it. You just don’t know when. You don’t know if you’re going to be one of the people who gets in a lifeboat or if you’re not going to get in a lifeboat.

“It’s just a bit of a sense of impending doom.

“But at the same time, there’s also this feeling of a kind of comfort in having some answers – answers in terms of why I’ve been feeling weird for the last few years and also I think every person … thinks about ‘I wonder what is going to get me?’

“It’s odd to get your answer … and being able to plan your life accordingly.”

Ultra competitive and whip smart, Lawson had always wanted to be a journalist but found an early love for media communications.

She graduated from high school with an OP1, completed a Bachelor of Business and Communications at Queensland University of Technology, and worked for the university’s communications team while studying.

Lawson went on to work for Ergon Energy and the federal government as a communications manager before taking a year off to travel the world and work overseas.

In 2008, she went into business with a journalist friend, Malcolm Cole, founding Cole Lawson Communications. The company did well, securing valuable clients and staking its claim in the public relations world.

One client came to the firm in 2009 asking for help in managing their media dealings. Representing a number of motorcycle gangs and clubs, the United Motorcycle Council (UMC) wanted help voicing its concerns about tough new legislation the Anna Bligh government was planning to introduce.

The laws would declare bikie gangs criminal organisations, place control orders on individual members, stop them from associating and order the removal of club house fortifications.

Cole Lawson Communications took them on as a client and – despite criticism – won a PR industry award for the work. Four years later, the firm was representing them again.

The Liberal National Party government, led by Campbell Newman, had drafted a raft of anti-bikie laws in the wake of a mass brawl involving about 50 Bandidos outside a Gold Coast restaurant.

The Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act was passed just a few weeks later, making it illegal for bikies to wear colours, have clubhouses or meet in groups.

Anyone declared a “vicious lawless associate” who was convicted of a specific range of criminal offences would be given an extra 15 years’ jail for their bikie status or an extra 25 years if they were a club office bearer.

One of the first to be charged under the new laws was a mother and library assistant with multiple sclerosis who was wearing club colours while with two members of the Life and Death Motorcycle Club at the Dayboro Hotel.

The woman – who was not a club member – faced a six-month mandatory prison sentence but received only a $150 fine for breaching the Liquor Act after the association charge was dropped.

Years later, Newman would admit they’d got it wrong. “Looking back on the whole thing, I just don’t believe that it was necessary,” he told the Gold Coast Bulletin in 2023.

“I didn’t want them to go after people enjoying riding a Harley-Davidson. I’m sorry that those people were impacted in that way. It wasn’t the intent at all.”

Lawson says she is proud of the work she did. “Cole Lawson’s campaign wasn’t about promoting or endorsing motorcycle clubs,” she says. “It was about calling out a bad law that could impact any Queenslander.

“The laws gave that government a huge amount of power to put people in jail without a crime having occurred, and that was a fact that needed to be part of the discussion.”

Cole and Lawson would eventually part ways business-wise, with Lawson choosing to maintain the double-barrel company name. (“It sounds more balanced, like a law firm,” she says.) Today, Cole Lawson employs about a dozen people, represents clients from aviation, banking, energy, aged care, technology and non-profit industries, and has a dozen industry awards recognising its work.

The firm now shares an office with Cole’s lobbying company, SAS Group.

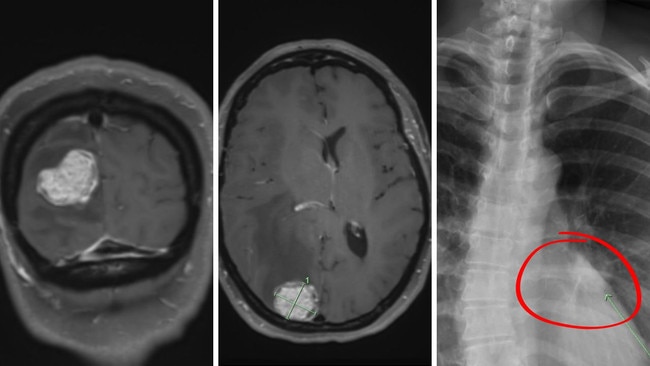

A scan of Lawson’s brain had found multiple tumours as well as “significant pressure from fluid”. She was told the tumours were likely secondary cancers. The primary cancer would be something else. Perhaps melanoma. They told her she didn’t want lung cancer. It was the least treatable of the cancers she might have.

Within an hour they had a theory. Metastatic lung cancer. A large tumour had been growing – perhaps for years – in her lower left lung, the cancer cells making their way to her brain.

The hospital organised an ambulance to take her to the neurosurgery wing of the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, friend Cross by her side.

They had been planning a craniotomy but Lawson had been downing aspirin for days, ruling out the procedure.

She’d told her parents where she was but not much more. Her sister Michelle Lawson, a teacher’s aide eight years her senior, had her phone on “do not disturb” while she was with a class.

At 1pm, Michelle took her phone out to Google something for a year 3 student.

“All these missed calls popped up,” Michelle recalls. “I thought ‘that’s odd’. And then, the most understated message (from Margaret). It said: “It’s an emergency. Are you available? I’m at the hospital.”

Their mother, at 87, had recently broken a couple of ribs and so that’s where Michelle’s thoughts immediately turned.

“I rang (Margaret) and said, ‘Is it Mum or Dad?’, and she said, ‘It’s me – I’ve got six or seven brain tumours and I’ve got lung cancer.’”

They’d had a cousin, a fit and healthy medical doctor in her 40s who’d had the same thing. She’d died within six months.

“I’m like Rhonda,” Lawson told her sister. “I’m going to die.”

Michelle drove to their parents’ home on the north side of Brisbane and sat with them on a low wall outside. She took both their hands in hers.

“I got to tell Mum and Dad that their baby had a stage four cancer diagnosis,” Michelle says. “I’m glad she didn’t have to do that. My poor parents – they are beautiful, wonderful, kind people. It’s awful, just awful.”

Lawson was admitted on a Monday. On the Wednesday, doctors performed a bronchoscopy to take a biopsy of her lung tumour. On Friday, she had her 46th birthday in a hospital room, friends and family gathering around to mark the occasion.

Eleven days after she first walked into a hospital emergency department with a headache, Lawson was given a full genetic typing of her cancer.

She had epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletion, a type of non-small cell lung cancer often seen in people who have never smoked.

Lung Foundation Australia CEO Mark Brooke says lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Australia and worldwide but receives limited funding and research.

Most people who develop lung cancer have a history of smoking but about 30 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men who are diagnosed have no such history.

Lung cancer in people who have never smoked occurs more frequently in women, and generally at a younger age than in smokers. No one knows why.

“One of the more startling things we are seeing as an emerging area of concern is women in their mid-30s to 50s who are ‘never smokers’ being some of the most significant findings,” Brooke says.

He says many people with lung cancer don’t experience any symptoms until the cancer has already spread. “Margaret was like that,” he says. “Most are diagnosed at a late stage of the disease, stage three or four.

“That’s when our treatment options – although there have been very good advances in precision medicine – are very limited. Margaret is not alone. As we come into lung cancer month (November), this is increasingly becoming an area of growing health burden.”

Brooke says the tragedy about our most lethal cancer is the stigma attached.

“The shame of people somehow mistakenly believing that because you smoked you brought this on yourself,” he says. “Regardless of whether you smoked or not, nobody deserves to have a diagnosis of cancer. The stigma of lung cancer remains all prevailing.

“We haven’t got the funding we require for research, for specialist nurses.

“People with lung cancer have the right to a gold standard of care.

“It’s the leading cause of cancer death here in Australia and the leading cause globally, and that’s not going to change any time soon.”

The first lung cancer screening program is expected to launch next year in the hope that early detection will give people a higher chance of survival and more treatment options.

It will be accessible to people who are at high risk of developing lung cancer who are not experiencing any symptoms.

The program is for people aged between 50 and 70.

Brooke says that while the screening program is an excellent initiative, there is no screening program available to people of Lawson’s demographic.

He says people should consult their doctor if they have a lingering cough that won’t go away – four to six weeks is considered abnormal – fatigue, breathlessness, weight gain or weight loss or changes to appetite.

“Not being able to do the things you would normally do, getting tired walking up and down the stairs or hanging up the washing – these are all signals that perhaps something isn’t right,” he says.

Recently, Lawson signed on as an ambassador for Lung Foundation Australia. It is in this capacity that she is telling her story. She hopes that by helping spread awareness, perhaps even one person might press for an answer as to why things haven’t been quite right.

On reflection, Lawson knows there were signs. She’d been to see an optometrist because her vision had been failing. Her tennis backhand had gone. Mood swings, fatigue, clumsiness. Her typing had gotten sloppy. The New York Times puzzle app had been getting more and more difficult.

Lawson attributed most of it to ageing or her busy lifestyle – all while tumours were growing in her lungs and brain.

“If I could go back in time, what could I have done differently?” she says.

“It’s not like I’ve ever been a smoker, so that’s not something that I can change.

“But then I think, well, if I’d known that this was a risk, when I had a terrible chest infection and cough about a year ago, rather than just asking for some antibiotics, I probably would have asked a doctor for a referral to get my lungs checked.

“I’ve always been on top of my health screenings, so I thought I was doing everything right. We hear so much about cervical cancer that I was so vigilant about those, but never really thought about air quality or lung health.”

Lawson was discharged from the hospital on June 14 with a raft of medications, including paracetamol and oxycodone for the severe pain she’d developed in her chest following the bronchoscopy.

Her discharge papers noted “identified area of loculation vs consolidation that could represent possible infection … likely post-bronch changes as expected”.

In fact, it was an infection – and one that nearly ended her cancer journey as quickly as it began.

By late June, she was back in hospital, this time at The Wesley Hospital. Her left lung was carrying an extra 2L of fluid from an infection near the tumour they’d taken a biopsy from. She had pneumonia and a partially collapsed lung.

A surgeon would clean out the infection and remove part of her left lung – and with it the major tumour. Helpful, but not a cure, it left her with a scar stretching halfway across her body that could easily pass as a tussle with a great white shark.

“Margaret is so determined to do her best at everything she does,” sister Michelle says.

“From day one, whatever rehab they’ve set her, she’s done double. Mediocrity is not her thing.

“No one would have judged her if she’d just said, ‘I could not be bothered’. But she knows no other speed than fast forward.”

Lawson’s sister and parents have been banned from crying in front of her. They cry for her in the hospital hallway instead.

“Cancer doesn’t just affect the patient,” Michelle says. “There is this devastating ripple effect that impacts anyone who loves the patient.”

In the office of Dr David Grimes, Lawson listened as the oncologist discussed how her cancer was responding to a relatively new drug: osimertinib.

Used to treat non-small cell lung carcinomas with specific mutations, it’s taken once a day in tablet form. Grimes has a plan for if and when the drug becomes less effective, and a plan after that, too.

But on this day, Lawson is concerned about her radiology report, which she has received prior to her appointment.

There is a mention of spots on her liver and bones and some in her brain that have not shrunk since the last scan. She worries it is a further spreading of her cancer, or a sign her medication is no longer working.

But the news is good: The doctor explains the spots on her brain, the ones that haven’t shrunk, are sort of like scar tissue, most likely remnants of dead cancer cells. He tells Lawson her existing tumours have shrunk, making new tumours unlikely – for now.

Michelle is in the waiting room, filing her nails, as Lawson is given this small reprieve. The sisters smile as they walk towards Michelle’s car.

When Lawson was six years old, she climbed the fence of a roadside paddock while on a family holiday in New Zealand and on to the back of a friendly horse.

When called for breakfast, it cantered its way to its owner somewhere else on the property. He was confronted with a strange little girl riding bareback, clutching the horse’s mane. Lawson developed an early love for animals – particularly horses – and the logo on Brisbane’s Exhibition Equestrian Centre was designed in memory of her horse Robbie.

It’s one of the few dreams she did not achieve, to be a jockey. But she knows she achieved so many others.

The business she built that is still going strong, the adventures she’s had to every continent, her passion for music that’s seen her write songs with and for famous musicians.

Lawson is treating her diagnosis like an early semi-retirement. And while she is planning new adventures, she is also planning something else: her funeral.

It will be no place for tears. She is planning a celebration with Champagne, live music and fabulous food.

She wants her old friend Malcolm Cole to emcee, knowing he’ll be hilarious.

“And while being respectful to those members of my family who are traditional, I would still want it to reflect my personality and have everyone go away feeling a little bit uplifted by the experience,” Lawson says.

“I would rather give the people I know and love an opportunity to go to something where they can have a little bit of a laugh. I have so many people in my life that I am so grateful for and I don’t want to think of them standing around crying.” ■

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Katy Perry got this really wrong – it’s time to come clean

Imagine going all the way up to space and coming back and telling everyone only the most banal details.

My origins: Claudia Karvan digs deep into her DNA

Actor Claudia Karvan was blown away by what she learned from the genealogy program Who Do You Think You Are? – surprised by the many traits she has inherited from her ancestors.