How Sydney sisters changed the Australian film industry from 1926

Three Sydney sisters who had no training in film production made a silent film so well received in 1926, they turned a corner of Sydney’s inner west into our version of Hollywood.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The black and white scene opens on a group of people enjoying a beach party, a young woman gets up and starts doing the Charleston. We cut to a scene in a seedy bar, a woman watches a drunk man sitting alone at a table, before a fight breaks out. The reel ends as a woman meets her lover at a wharf, kissing him as a couple of dockworkers look on.

The whole thing lasts less than three minutes, but it is all that remains of the debut feature film, Those Who Love, which premiered in Sydney in September 1926 to rave reviews.

The filmmakers? Three Sydney sisters who, while they had no training in film production, made a silent film that was favourably compared to a Charlie Chaplin flick and is said to have made the then-governor of NSW, Sir Dudley de Chair, weep in the audience.

Isabel, Phyllis and Paulette McDonagh were in their 20s and, for six years during the Great Depression, entertained Sydney theatregoers with their melodramas which they financed, directed, produced, edited, promoted and even acted in themselves, paving the way for the likes of Australian Oscar nominee and power producer Nicole Kidman.

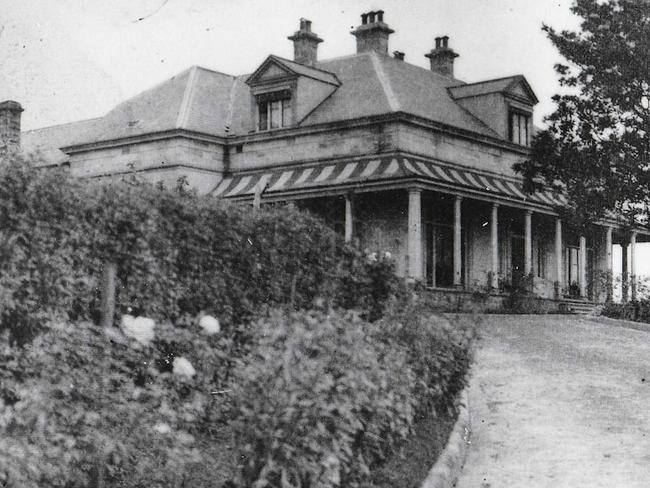

The scenes were shot around Sydney including in their own home – the stately inner-west mansion Drummoyne House – with their friends playing bit roles and using the very modern idea of product placement to encourage car, fashion and building owners to loan them props for free in exchange for promotion on film.

Those Who Love is a tale about the son of a wealthy family, Barry, who falls in love with a poor but well-meaning woman named Lola, played by Isabel McDonagh who used the stage name Marie Lorraine.

While the sisters filled most roles on the set themselves, they employed former Hollywood cameraman Jack Fletcher, spending about £2000 to make the film over four weeks.

But it made back £4000, which was enough to finance a second film and earn them the reputation of being pioneers in the Australian filmmaking industry and the first Australian women to own a production company.

Isabel, Phyllis and Paulette were born in 1899, 1900 and 1901 respectively to Dr John McDonagh, a surgeon for theatre promoter JC Williamson’s troupe, and Annie.

Their father’s professional involvement in the theatre industry meant the girls – the three eldest of seven children – grew up in this bohemian world. But their father, who died in 1920, and their mother, who followed in 1924, would never see their daughters’ film success.

It was with the money left to them in their parent’s will that they set about making their first film, conceived while the three were away at boarding school.

Their second film was The Far Paradise, released two years later in 1928, and while it was also successful, it did not earn as much as their first film and they struggled to make their third, The Cheaters, released in 1929. It was this film, which came out when the first American talkies were flooding the Australian market, that proved their undoing.

In a bid to compete in the Commonwealth Film Prize, they reproduced it as a talkie by using the less-sophisticated sound-on-disc method which plays the sound on different equipment to the film. It fell out of sequence at the official screening and was reported a failure, earning the ladies a disappointing fourth place.

Their fourth and final movie, a World War I feature called The Two Minutes’ Silence financed by Isabel’s future husband Charles Stewart, was also a box-office flop. They would go on to make some documentaries, including one about Phar Lap and another on Donald Bradman, but they would never make another movie.

Phyllis moved to New Zealand to work as a journalist and died in 1978. Paulette, the only one who remained in Sydney and attempted unsuccessfully to raise funds for more films, also died in 1978. And Isabel, who moved to London with her husband and had three children, died in 1982.

Snippets of their films are kept with the National Film & Sound Archive.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedesmaguire@news.com.au

DRUMMOYNE’S FILM STUDIO

The stone mansion fronting Parramatta River was built in the late 1850s by merchant William Wright who lived there with his wife Bethia until his death in 1889. It was renowned for its gardens, which included an orchard, kitchen garden and a croquet lawn.

It had various tenants and owners throughout the early 1900s, including department store owner Anthony Hordern and the McDonagh family, who converted two wings into a convalescent home in the 1920s to help bring in an income, while another section was retained as a film studio.

It was demolished in 1971 and flats are on the site today.

OUR LOVELY MOVIE STAR

Nellie Louise Carbasse was born in Paddington, Sydney, in 1895 to an Italian father and Swiss mother. She made her stage debut at the age of nine and went on to appear in several films prior to WWI before heading to Hollywood in 1914 and changing her surname to Lovely.

She was contracted to Universal Pictures and also made movies for 20th Century Fox. She starred in a total of 50 films, before returning to Australia in 1924.

She retired from acting in 1925 and lived out her years in Hobart. She died in 1980, aged 85.

How fortunes changed for Point Piper’s namesake

Oh to be a guest at one of John Piper’s great gatherings.

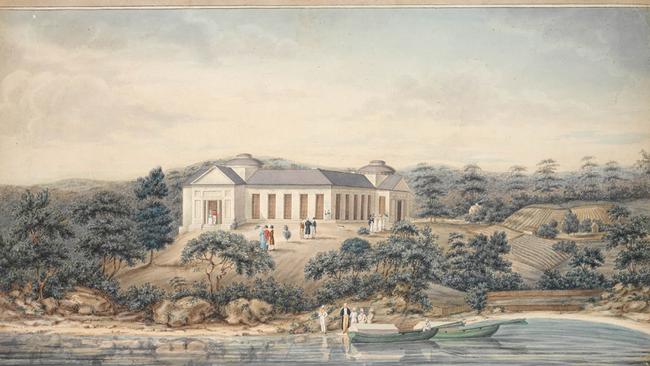

If you arrived by carriage, you would have travelled along the road constructed purely to connect his grand Henrietta Villa to Sydney town. And if you arrived by boat, you would have been greeted by the boom from a row of brass cannons positioned outside Piper’s home on the Sydney Harbour foreshore.

Once at Henrietta Villa, you would have sat down for a decadent meal in the banquet hall then danced the night away in the magnificent domed ballroom.

Henrietta Villa was described in 1824 as “a home unrivalled in the colony” and an invitation to the famed address was an honour for the dignitaries of Sydney town.

Completed in 1822 at a cost of £10,000 (about $1.35m today) Henrietta Villa, for all its opulence and fame, would last only several decades, demolished in the 1850s after Piper lost his wealth and moved to Bathurst.

Today, a plaque honours Captain John Piper out the front of Rose Bay Police Station on Wunulla Rd. It marks the spot where the fashionable elite of Sydney once arrived through a grand entrance.

His legacy and name, if not his beautiful home, remain a prominent part of the still-prestigious Sydney suburb.

John Piper was born in Scotland in 1773 and came to Australia in 1792 as part of the newly-formed NSW Corps, posted to the penal settlement at Norfolk Island.

He travelled back and forth between Sydney and Norfolk Island, returning permanently to Sydney in 1810, which meant he had missed the chaotic events of the Rum Rebellion in 1808.

Promoted to captain, he married Mary Ann Shears, the daughter of a convict he met on Norfolk Island, on February 10, 1816, and that same year laid the foundation stone for Henrietta Villa on land granted to him by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, although the land grant was not formalised until 1820.

On December 2, 1819, the Sydney Gazette reported on a “fete champetre” – or garden party – held at Henrietta Villa even though it wasn’t yet complete and the Piper family had not yet moved in.

“About 100 ladies and gentlemen sat down to dinner; after which the merry dance commenced which was kept up with great spirit; and on the party leaving Henrietta Villa they were saluted by a discharge of 15 guns,” the Gazette wrote.

Davina Jackson, author of Australian Architecture: A History, says historians can’t say for certain who designed the white neoclassical palace, but it is believed to be either convict architect Francis Greenway, English architect Henry Kitchen or an unknown architect.

But what is not disputed is that the Villa was a prominent building in the early colony.

“Although it was only one storey, Henrietta Villa boasted soaring ceilings, generous verandas and shallow domes over the entrance hall and ballroom-banquet hall,” Jackson says.

Despite a career that included a lucrative naval officer commission in 1813, which involved collecting customs duties, an appointment of magistrate in 1819 and a role as chairman of the newly-formed Bank of NSW in 1825 (as well as land holdings in Woollahra, Vaucluse, Neutral Bay, Petersham, Bathurst and Tasmania) Piper’s fortunes turned swiftly in 1826.

Governor Ralph Darling questioned his financial mismanagement of the bank, though not his honesty, forcing him to resign.

A story was circulated that after making a will, Piper invited his closest friends to Henrietta Villa to dine, then he had his crew row him out beyond Sydney Heads where he jumped overboard. He was rescued by his crew and returned to Henrietta Villa.

The Piper family retired to an estate in Bathurst but the 1838 drought further crippled him financially and, with the aid of friends, the Pipers relocated to a home on Macquarie River in the NSW Central Highlands. Piper died there on June 8, 1851, aged 78.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

RISE AND FALL OF WOOLLAHRA HOUSE

Woollahra House was built on the site of Henrietta Villa in 1856 by Sir Daniel Cooper, a merchant and a politician. He sold it to his son, William Charles Cooper, who built the second Woollahra House there in 1883.

When Cooper returned to England five years later, Woollahra House was rented out to various society people until the land was subdivided in 1899.

Industrialist Thomas Longworth bought the portion with Woollahra House on it but it was demolished in 1929.

The gatekeeper’s lodge is today the Rose Bay Police Station and the stables were converted into a block of flats.

OUR CONVICT ARCHITECT

Francis Greenway was already a respected architect in England when he pleaded guilty to forging a document and was transported to NSW in 1814.

While still a convict, he designed Macquarie Lighthouse on South Head in 1818 and as a result was emancipated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie and appointed the colony’s first architect.

He was responsible for many public buildings, including St James’ Church in Sydney and Hyde Park Barracks.

He died of typhoid in Newcastle in 1837, aged 59. His face graced Australia’s first $10 note, which was in circulation from 1966 to 1993.

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au