Madeleine West interviews refugee Fadak Alfayadh

Fadak Alfayadh and her family fled war-torn Iraq when she was 10 years old. Now a Melbourne lawyer, she sits down with actor Madeleine West to share her story of growing up as a refugee in Australia.

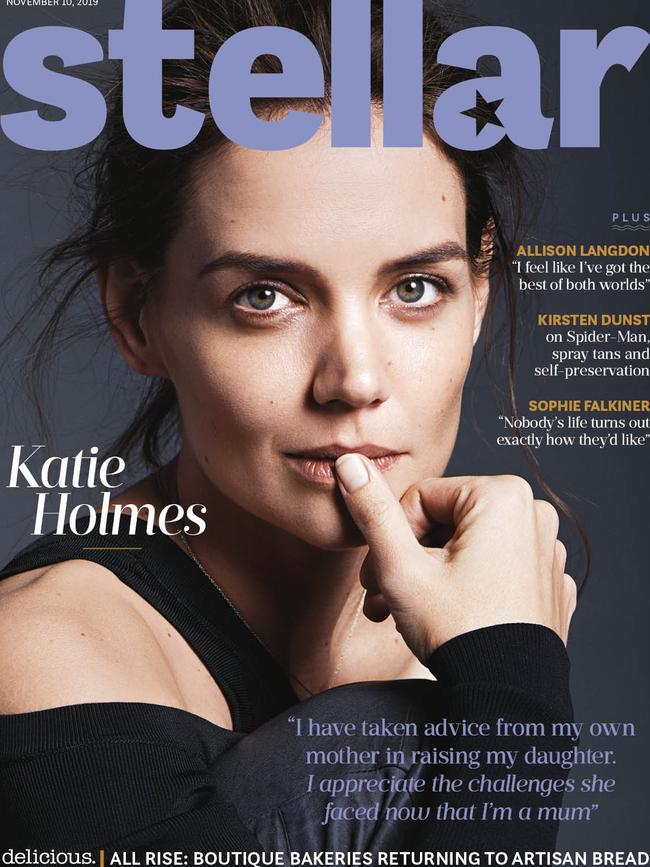

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fadak Alfayadh pauses, sips delicately from her cup of espresso, and launches into an impassioned discourse about the plight of Melbourne’s homeless and the epidemic of domestic violence.

Only moments before, we were giggling helplessly at her account of a recent trip to the Mercedes-Benz Fashion Festival in Sydney as a guest of Dior.

To converse with this remarkable 27-year-old is to receive a lesson in humanity – you walk away wanting to strive to be your very best, and then use that platform to ensure those without a voice have the chance to do the same.

Alfayadh is a lawyer. She is also a communications manager, a TEDx talk presenter and an outspoken champion of society’s disenfranchised and dispossessed.

She is elegant and eloquent – the kind of young professional that upper-crust universities and leafy eastern suburbs jostle to proudly call their own.

So it can seem inconceivable that the final memories of her homeland are of huddling beside her sisters beneath a staircase in Baghdad, wrapped in her mother’s arms as bombs obliterated all she had ever known.

Perhaps even more difficult to contemplate is that her first impressions of Australia were glimpsed from behind the walls of an asylum-seeker processing facility: “My name is Fadak, I am Australian, and I am a refugee from Iraq.”

When she was five, her doctor father Jalal was conscripted to Saddam Hussein’s army. Objecting would sign his death warrant, so he fled, via Malaysia and by boat, to Australia as a refugee, one forced to leave his young family behind.

It would be six years before they could join him. “Iraq was home,” Alfayadh tells me with a sigh. “Life under a dictatorship is crushing but my mother was content to wait for our opportunity to join my dad in Australia.”

Their patience was tested daily – the spectre of a looming invasion meant constantly sandbagging their home and stockpiling food.

By 2003, that life became untenable. “Mum hid us in the back of the car, we drove through the night with the lights off, and waited a full day at the border, having to bribe officials, before finally entering Jordan,” recalls Alfayadh.

They applied to the Australian Consulate for residency, and her first impression of the lucky country actually occurred far from these shores. As she and her siblings passed through immigration in Malaysia, an imposing Australian customs officer waited with them while her mother was interviewed.

“I had no idea what he was saying,” she says wistfully. “But I do remember wondering why he smiled so much, why he made the effort to hunker down and talk to us on our level. He made me feel safe, welcome. So he came to symbolise Australia.”

Once here and reunited with her father, Alfayadh and her family eventually settled in Dandenong, just in time for Christmas.

“We had fled a world of colour, movement, fear and devastation, a world ravaged by war,” she says. “Christmas in Australia presented a world of colour, movement and light. It was a world defined by beauty, and so much love.”

Enrolled in school, she recalls, “I never felt like an outsider, because there were kids from all over the world in my classroom and community – from Albania, to the Congo and Turkey.”

But the language barrier seemed insurmountable. “I was a top student in Iraq,” she says. “My intelligence defined me, it was how I identified myself. But without the words to express myself, I felt invisible... worthless.”

In a tragic twist of fate, and mere months after they were brought together again, her father was killed in a car accident. Now even the sound of thunder felt like a threat, recalling bomb blasts, death and devastation.

Without a solid grasp of the language, she struggled to express the trauma of war; her grief, her fear. Then along came her Year 6 teacher, Mrs Surace. “She was tall, with blonde curly hair,” says Alfayadh as her eyes well with tears.

“Initially, I didn’t understand most of what she said, but she was instrumental in me becoming who I am today.”

Mrs Surace equipped her students – many of them refugees and witnesses to the horrific atrocities men wilfully inflict upon each other – with tools to be the best version of themselves.

“It was more UN than a classroom, but she took time outside of school to patiently wade through children’s books so I could grasp English,” says Alfayadh.

“I could then tackle maths, science, start friendships. I could express myself. I felt understood. I felt I belonged. Mrs Surace probably did the same for every struggling kid in her classroom, but her care demonstrated she saw potential in me. I felt seen... That was all the motivation I needed.”

MORE STELLAR:

Liz Cambage: ‘Look at the facts: I am great’

How do I tell my richer friends I have money issues?

Post-Tampa and the Children Overboard affair, much of her stress was fuelled by an increasing sense of unease about her place in Australia.

The events of 9/11 had demonised an entire culture, so her Arabic heritage became a source of shame, and she experienced racial vilification in casual acts of cruelty.

“I was constantly teased about my lunchbox,” she says, wincing at the memory. “Middle Eastern food is everywhere now, but back then, amongst a sea of Vegemite sandwiches, it was smelly and messy. I felt ashamed about who I was.”

Small acts of kindness ended up having great impact. She tells me of a time when Mrs Surace asked if she could try one of her mum’s homemade rice dumplings. “She took a bite and started rhapsodising, ‘Oh! So delicious. So beautiful!’ I had to ask my mum what ‘beautiful’ meant.

From that day forward, my classmates became curious instead of cruel about my lunch and my culture. Despite some Australia doesn’t want Muslims’ rhetoric, my community didn’t fear me, they wanted me to succeed... that is why I wanted to share my story – I wanted to change the world.”

So she went on to study law and politics. Migrant advocacy in a community legal centre, public speaking engagements, and commentary in the media followed. The culmination was Meet Fadak, a national speaking tour aimed at breaking down walls.

She recently represented refugees at the annual United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) NGO Consultations in Geneva.

“I want to change the narrative for refugees and asylum seekers,” she explains. “Meeting people who have always been an ‘unknown quantity’ to us creates common ground, bonds and communities. I’m often surprised to discover how much we share.”

The asylum seeker issue is as complex and multilayered as Australia’s cultural identity, but Alfayadh says that at its heart is the need to embrace commonality by putting a human face on an escalating moral crisis.

“If people meet me and hear me out, their negative connotation towards refugees might shift.”

Small shifts can prompt seismic change, hence our mutual involvement in the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC)’s The Story Beside You campaign, which celebrates those who overcame seemingly impossible odds to call Australia home – their faces plastered on trams in Melbourne as part of the Yarra Trams Community Partnerships Program.

We are encouraging them not just to tell their stories, but to listen to the responses.

Or, as Alfayadh observes with trademark eloquence, “There has to be more story sharing, more talking, more getting to know each other. There is a lot more that unites us than divides us.”

To learn more and sign #TheStoryBesideYou pledge welcoming refugees to Australia, visit asrc.org.au/stories.