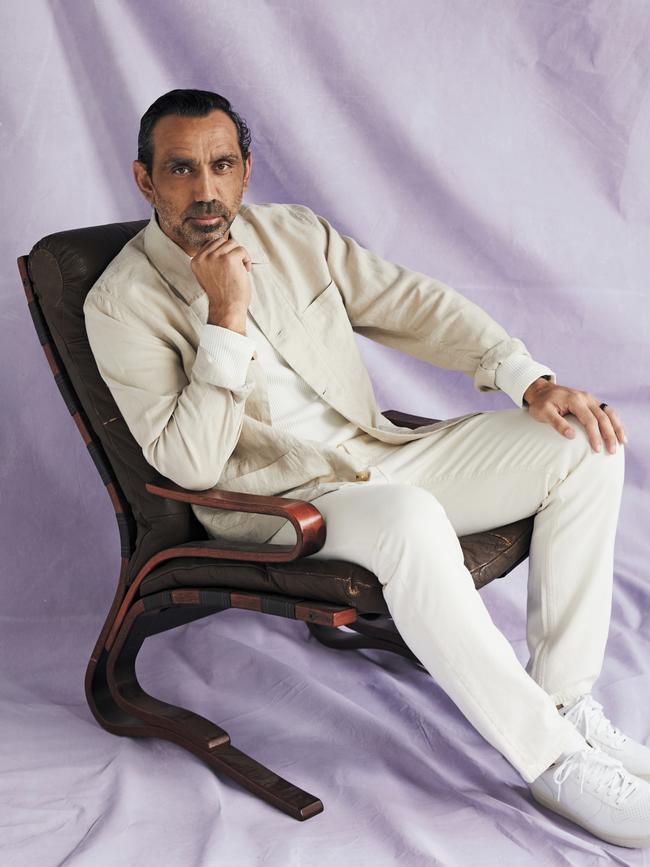

Adam Goodes: ‘It’s a chance to put a black person’s face on a busy corner’

Speaking openly with Joe Hildebrand, Adam Goodes reveals how it felt to see his own face on a mural and his big plans to bring Indigenous stories to the wider population, starting with his own daughter.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Cathy Freeman: ‘People, for that small moment, became equal’

- Michael Clarke on his first Father’s Day as a single dad

The legend of Adam Goodes permeates deep and wide within the Australian psyche. He is an almost unrivalled star in our native sport, was given our nation’s highest honour and became a lightning rod for heroism and hate when he found himself in the vortex of an ugly wave of pack brutality.

And so he looms like a Greco-Roman god: a figure of worship, a symbol of conflict and a cipher for explaining dark truths about ourselves that perhaps we’d rather not gaze upon directly.

He also looms, literally. In inner-city Sydney, heartland of his beloved Swans, a giant mural of his image is plastered across the full side of a building. But Goodes is not a god. He is just a man, one who has no time to dissect his own mythology. So about that mural? “Well,” he tells Stellar, his voice deadpan, “it cost me a lot of money to paint it.”

The mural was something the building’s owner asked him for permission to undertake more than 18 months ago, but never got around to it. Then when the death of George Floyd electrified America and sent ripple effects to Australia’s Indigenous community, that owner and the artists he would eventually engage decided the time was right.

“He was like, ‘You know what? With everything going on in the world, we’re just going to do it. Are you still OK with it?’” Goodes recalls. “I said, ‘Yep.’ For me, this is an opportunity for people to see what was going on around the world with the Black Lives Matter movement – and to put a black person’s face on a busy corner and to celebrate that sort of symbol means my face on a building.”

But Goodes has little time to marvel at his own greatness. In fact, he wasn’t even sure which corner it was on. “I’ve only driven past it once and that was by accident and I thought ‘Oh my goodness!’ I can only imagine what it would look like my standing there, looking at myself.”

Perhaps the most striking thing about Goodes is that someone so iconic is so casual, funny and self-deprecating in person. When we catch up at his photo shoot for Stellar, he is joking about his new-found glamour as a male model.

Goodes is here as an ambassador for David Jones, but the real reason he does the job is to raise awareness and money for the Australian Literacy & Numeracy Foundation (ALNF). This week, David Jones will launch and sell designer “Literacy Is Freedom” T-shirts that will channel vital funds back into the ALNF’s life-changing programs.

But all this posing up seems to be taking a back seat to his preoccupation with a dodgy hamstring, one that will stop him playing soccer on the weekend. Yes, the dual Brownlow medallist is now a daggy suburban soccer-playing dad, albeit one who gets tips from former Socceroos star Craig Foster.

You have to pity the other blokes pitted against him. For all the lionising of Goodes as an angel, it’s easy to forget that he is a ferociously driven warrior – and not just on the playing field.

The next goal Goodes has his eye on is getting a First Nations voice to Parliament, as called for by the Uluru Statement From The Heart. When hundreds of Indigenous leaders were sent to the Red Centre to develop a form of constitutional recognition in 2017, the Malcolm Turnbull government was shocked when they came back with a proposal not for some token words, but an enshrined constitutional voice.

The then-PM panicked that this would be a so-called “third chamber of parliament”, and Indigenous recognition was shelved once more.

Three years later, Goodes is still palpably unhappy. “The government pie-faced us once again when they asked what we think and what we want,” he says.

“That’s just another slap in the face for Indigenous people and leaders. But we’re now out there working with corporations and CEOs to make them aware of the statement. We, as a small part of the population, can’t get this over the line. We need the people of Australia to understand what it is and what we can play to make that a reality.”

When he retired from football, Goodes cast his eyes far and wide to seek out where he could do the most good, particularly for Indigenous communities – often the most disadvantaged and obviously the closest to his heart.

He quickly realised the magic bullet was to tackle that disadvantage before it calcified, by giving children the tools they needed for success in life, and as early as possible. Hence the ALNF is teaching them before they even get to school and, just as importantly, engaging their parents, as well.

Of course, this goes beyond being a mere academic exercise for Goodes. He and wife Natalie Croker are now parents, and their daughter Adelaide, who was born in June 2019, is just starting to walk and talk. He reads to her constantly and sees first hand how language makes children come alive.

This is extremely personal for him. As a child, he never learnt his own Indigenous language and so he is making sure that his daughter knows hers, right down to her middle name. It’s Vira, and it means moon. “We want to keep using words like ‘hello’ and say ‘nangga’ so she knows they mean the same thing. It’s something I didn’t have growing up, so we think it’s important to teach Adelaide,” he tells Stellar.

He is also working on a major project to develop stories to help both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children and parents across Australia understand our shared history. “Storytelling is a part of Indigenous culture,” he says. “It’s a way to educate everyone, all Australians, of our past and our journey, and who we want to be moving forward.”

And that’s also central to Goodes’ understanding of himself. “There’s always been something missing in my life. And that was the ability to identify as an Indigenous man, and for me to go on that journey to learn about our history.” These days, of course, Goodes hasn’t just learnt about history. He has also made some himself.

To get a T-shirt and support Indigenous literacy programs, go to davidjones.com/alnf.