Cathy Freeman: ‘People, for that small moment, became equal’

Notoriously private Olympic athlete Cathy Freeman grants a rare interview to celebrate the milestone anniversary of her gold medal win, and reveals it was her daughter who has prompted her to revisit that history-making moment 20 years on.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“I’m not one to step into the light.” It may seem a strange observation coming from one of the most famous faces in the country, but Cathy Freeman is the first to acknowledge the irony of the situation.

“I’m a shy girl who makes my natural choices,” she tells Stellar. “The next thing, I find myself in places I wouldn’t have possibly imagined.”

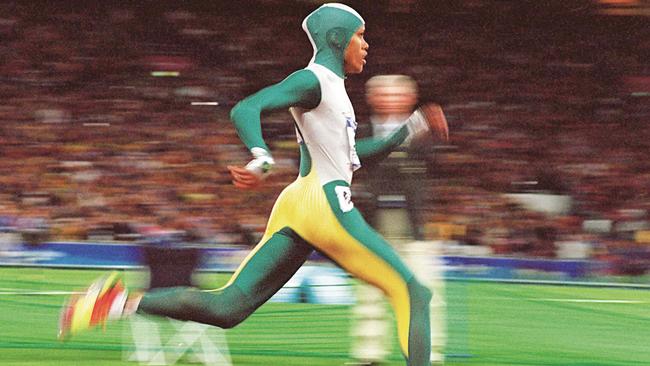

Twenty years ago this September, on a spring night in Sydney, Freeman found herself on the track at what was then called Stadium Australia, making history over the course of 49.11 seconds as she soared through the final of the women’s 400m at the 2000 Olympic Games.

Most of us know exactly where we were when she crossed the finish line in first place. The lounge room. A bar. The stadium itself, if we were really lucky.

Because Freeman did more than win gold that night. She united the country and created a moment when everyone, no matter the colour of their skin, was proud to be Australian.

Ironically, the one person averse to reflecting on what that night meant seems to be Freeman herself. In fact, her conversation with Stellar – which has been years in the making – marks the only print interview she will do to mark the milestone anniversary.

And up until six months ago, while she had watched the race many times before, Freeman had never really seen it. Up until that point, her nine-year-old daughter, who she shares with husband and manager James Murch, had only ever known her mother as Catherine Murch.

And it was her daughter’s questions and a growing curiosity that would finally inspire her mother to dive back into the memory vault.

“She was part of the reason I had to embrace all of this,” says Freeman. “She started to get an understanding that part of Mum was Cathy Freeman. This athlete, this Olympic champion.”

When kids at her daughter’s school started becoming aware of Freeman, the now 47-year-old knew it was time to start sharing more. “I didn’t want to omit information. It’s part of my family’s life. It just started to get ridiculous how I would get so funny talking about or watching something that made so many people happy. Even in the deepest crevices of my mind, I knew this was something that had to be shared. It’s almost an injustice not to share this sort of story.”

So after having spent years politely declining offers to tell her story on film, Freeman finally gave permission for director Laurence Billiet, who she met while making the 2006 series Going Bush, to do just that. And in the process of making the documentary, which would go on to be called Freeman, she finally confronted the footage from that night.

“It was so emotional watching it,” Freeman says. “The race itself was like counting to three. I am so familiar with it, but the actual environment outside the race was just extraordinary to me. I was so taken by people’s reactions. I saw things I was completely unaware of, like crossing the finish line and seeing the reaction of people in the stadium. I found that really incredible.”

Running has been Freeman’s salvation since her childhood in Mackay, the city on Queensland’s central coast where she grew up and where, at age five, she discovered an unadulterated love for the sport. She was the middle of five children, with a beloved older sister named Anne-Marie who had severe cerebral palsy and a supportive stepfather who wanted Freeman to pursue her passion. When she was 10 years old, he encouraged her to hang a sign that said “world’s greatest athlete” on her bedroom wall.

“I was such a shy kid, but I expressed a boldness and fierceness in my running,” Freeman recalls. “Running is the purest expression for me. I don’t think I could have endured what I did as an elite athlete if I didn’t simply love running.”

Getting on the track also helped Freeman – who growing up was denied medals because of the colour of her skin – embrace her Indigenous heritage. At 16 she became the first-ever Aboriginal Commonwealth Games medallist. Four years later at the event in Auckland, which took place three days before Anne-Marie’s death, her decision to drape the Australian and Aboriginal flags – or as she says, “the two Australian flags” – over her shoulders after winning a race caused an uproar. At the time, she responded by simply saying, “With all due respect, I don’t care. I’m just here to run.”

Her defiance and pride made her a symbol of hope for Indigenous Australians, which was only heightened in the lead-up to those fateful Olympic Games in 2000. That May, as part of the Corroboree, 250,000 people walked across the Harbour Bridge in the Walk for Reconciliation.

Her 400m race was always going to be a politically charged event. Freeman was the favourite after only having lost one race in four years, which was only because of an injury mid-race, but she would still need to face off with three-time Olympic champion and arch rival Marie-José Pérec of France.

While the pressure became too much for Pérec, who dramatically fled the Olympics days out from competition, Freeman carried the weight of a nation on her 163cm frame. She can still recount, as if it were yesterday, the noise of the stadium’s crowd vibrating through her body while she was warming up. “It’s like a beast. I’m nervous using that description because I don’t want people to feel insulted. But it had a beast-like presence,” she says. “I remember saying to myself, ‘Just do what you know.’”

She also has a vivid memory of a near out-of-body experience that took place as she was marshalled underneath the stadium before the race. “I hear a gentleman say, ‘Good on ya Cathy!’” she tells Stellar. “And literally everything turned dreamlike. I’ve never had a moment like that – before or since.”

From there she went on to autopilot. Walk out on to the track. Look to the sky and take a few deep breaths. Take off the tracksuit to reveal the famous Nike Swift Suit. Crouch down into position. Wait for the starter’s gun. Go.

In the film, Freeman describes the race itself as a moment of transcendence, and of feeling as if the spirits of her ancestors were carrying her. She was third when she came out of the bend into the finishing straight, but it obviously didn’t remain that way. Freeman strode across the finish line almost a second ahead of the field. The stadium might have erupted in elation, but Freeman’s first thought was: “I wish I’d ran faster.”

She says now, “That’s the athlete mindset. I’m never completely satisfied. I’m always reaching for more. I laugh about it now, because the bottom line is it was a pretty good result: Olympic champ. Best in the world against this scene with all the other moving parts. But I really would have loved to have got under 49 seconds.”

Freeman entered the nation’s heart – and its history books, becoming the 100th Australian to win an Olympic gold medal. While she never contemplated losing the race, Freeman does admit there was a time months before when she considered not running it at all.

“I remember ringing up to speak to my brother and got a message that he had gone fishing. For a minute I compared his life to mine. And in that moment I got a little bit jealous. I thought, ‘What am I doing?’ The penny had dropped that this was going to be a highly hyped event. Growing up Indigenous there was that social-justice background. [So] I fantasised about running away with my brother to go fishing. But obviously there were forces at play that had me be there.”

And those forces conspired to bring Australia one of its all-time greatest sporting moments. Sports journalist Phil “Buzz” Rothfield, who was covering the race as the Olympic Editor for News Corp, tells Stellar, “When Cathy crossed that line, it triggered the biggest sporting celebration this country has ever seen. We could hardly print enough newspapers. It sold out in nearly every suburb and every newsagent. Not just our regular readers but the internationals were all over it, too.”

Billiet was one of those internationals. She arrived in Australia from France in 1999, and jokes that she was a staunch supporter of Pérec’s until Freeman’s story transformed her. “As you get older you realise you don’t get to witness many moments like that in a lifetime,” she says. “It was so much more than a gold-medal win. It contained so many emotions, aspirations... and all of them still feel so tangible today.”

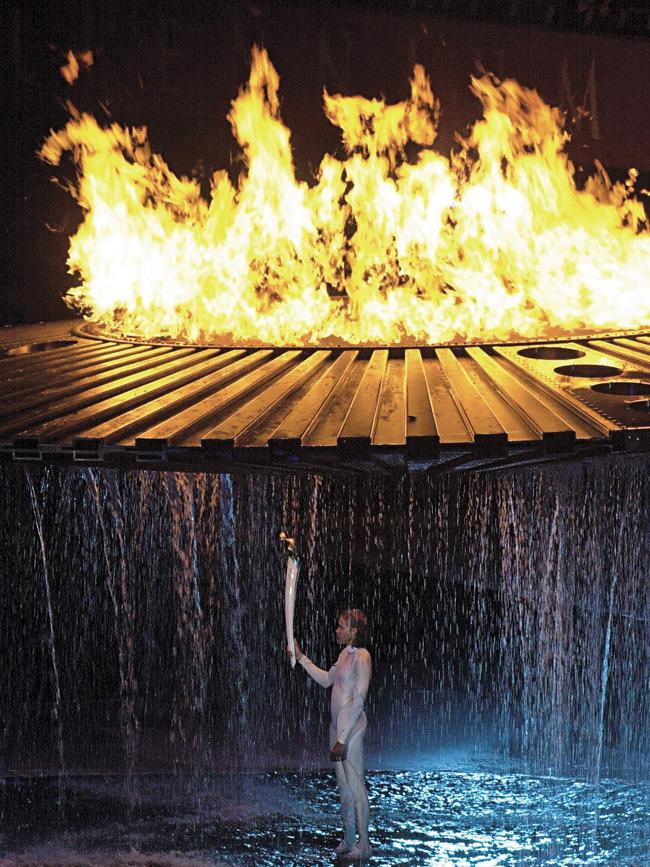

If the race wasn’t history-making enough, 10 days earlier Freeman was also charged with the responsibility of lighting the Olympic Cauldron at the opening ceremony. “I think I get more exhausted thinking about that moment than thinking about my running,” she says, laughing as she reflects on the glitch that saw the cauldron momentarily fail to move up a track to the top of the stadium.

“After the race, I wasn’t physically exhausted. But for the cauldron not to have restarted would have been terrible. It would have smashed the whole image of what the Olympics was all about.”

Nonetheless, the two billion people watching saw a composed 27-year-old hold the flame above her head and smile, but inside, Freeman, who hadn’t even told her mother she would be lighting the cauldron, was trying to comprehend the surreal nature of it all.

“I was already celebrating because I didn’t fall up the stairs, I didn’t fall down the steps, I didn’t fall in the water, I didn’t catch on fire. I was happy and then… I remember looking down at the cameraman when it didn’t move. He looked up at me and at the cauldron and then back behind the camera as if to say, ‘Whoops! OK, not my problem.’ And then I looked at the conductor and he looked up at the cauldron as if to say, ‘Whoops, it hasn’t started, not my problem!’ Those two minutes were the longest of my life.”

Freeman never ran in the Olympics again. She retired from competing in 2003 and only went to the 2004 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City as a flag carrier representing Oceania at the opening ceremony. And when she turned away from running, she had no plan B.

“One thing I knew for sure was that it was good to taste what normal life was like,” she says. “But, dare I say it, I did take my whole running career for granted. Because when you’re a teenager or in your early 20s, you think you are going to stay there forever. Now, in my infinite wisdom, I’m so grateful for that life I had as an elite athlete.”

She gave herself time to rest and get used to life as a non-athlete – there was less structure, and she did not necessarily need to concentrate on a goal. But by 2007, she was harnessing the same focus, determination and passion that made her a champion and pouring it into helping Indigenous children achieve their own version of a gold-medal moment through the establishment of her charity, the Cathy Freeman Foundation.

Freeman maintains her own path to greatness was only possible because of the support and encouragement from others, as well as education, which is what she hopes to pass on to the 1600 Queensland and Northern Territory children her charity supports. “Some of these students may never have been in a lift before or caught a plane, so the world is their oyster,” she says. “We are providing a path for them to take so they can experience the world. It’s lovely seeing their confidence grow, and that moment where they suddenly think of themselves in a whole new way.”

Since 2011, she has also been dedicated to nurturing the dreams of her own daughter. “[Motherhood is] the toughest gig ever,” she says. “Striking that balance between trying to let your child experience their lives in their way and giving them that freedom, but also being there to take control and have some say in the way they view the world.”

In everyday life in Melbourne where she lives, Freeman is – as her daughter can attest – simply known as Catherine Murch. “I am very proud to have my married name. [And] anyone who knows my family knows they cannot handle their daughter or their niece being called Cathy,” says Freeman, who was dubbed Cathy by a journalist at the inception

of her career. “Catherine feels more at home to me.”

And of course, she still runs. “I still love to run. There is that competitor and that athlete still in me. But then there is also the mum who just wants to get out and move her body because it’s healthy and I know it’s good for me. But when I run, even if it’s a really slow slog, it’s like going back to my childhood. While the physical experience is a bit different because of the ageing body, the freedom and the joy is all still there.”

The world has changed irrevocably in the 20 years since that historic night. “Sport enables people to get an insight into their own nature and sometimes this nature is a force of its own, which is where the real power is,” Freeman says. “I only have to cast my mind back to that night where people, for that small moment in time, became equal. That’s so powerful. Everyone is just there celebrating a victory and it’s one of the great privileges of my life to witness. Even though I am ordinary, it’s an extraordinary story.”

Freeman airs on ABC and iview on Sunday, September 13, at 7.40pm.