Shedia magazine: How Christos ‘Chris’ Alefantis is lifting Athens’ homeless out of the streets

One Australian is helping rebuild Athens, one magazine at a time. Christos Alefantis’ story is one of hope, charity — and success for the troubled city’s homeless.

Real Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

From a grand but crumbling building in the streets of central Athens, an Australian man is quietly helping the forgotten victims of the Greek economic crisis get back on their feet.

Christos “Chris’’ Alefantis, 53, moved from Melbourne a decade ago and now dedicates his life to getting those who have lost their jobs back into the workplace, and back into a home.

He publishes a street paper, Shedia, sold by homeless vendors, which has become the largest-selling magazine in Athens.

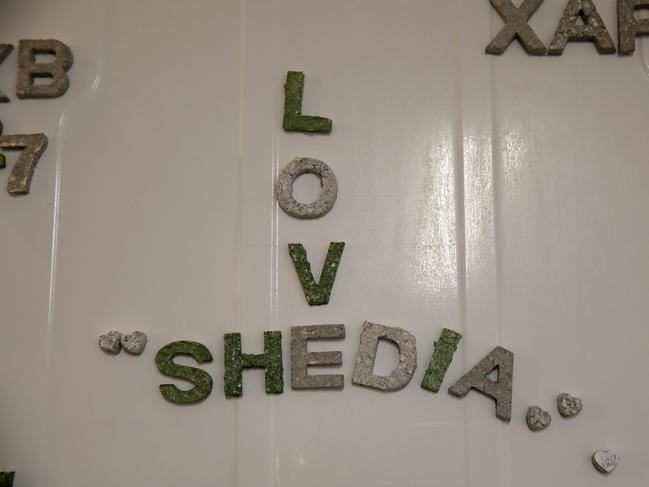

Leftover copies of the magazine are upcycled into pretty household objects, art and jewellery and sold in their shop.

Alefantis organises walking tours, where paying customers take tours through the Athens backstreets with homeless people who share the stories of their lives.

A Michelin-starred chef has helped his charity develop a cafe, restaurant and bar which will open shortly in their ground-floor offices, providing hospitality training and a career path for the vendors.

And what sets it all apart is the charity is built around a sustainable business model — it makes enough money to pay its own way, and teaches its vendors how pay their own way too.

“We have a business plan in place to be self-sustaining. There is no other way for us,’’ Alefantis told News Corp Australia.

The Australian-born son of Greek migrants who came from the Peloponnese with so many others to Melbourne in the 1950s — arriving at Station Pier, his dad moving to the Bonegilla migrant camp — Alefantis always maintained strong ties with Greece.

“I moved here in 2005 for a couple of years — those couple of years are now 13 years,’’ he said.

He’d lived in Brunswick St in Fitzroy and worked as a journalist at the Greek Herald, and was always active in the community.

Shortly before moving to Greece, he read about the Australian team in the world cup soccer event for homeless people, and was “blown away by the impact of how to launch a global voice against poverty’’.

In 2007, he launched a Greek team, which continues to this day.

But by the time the Greek economic crisis hit in 2009-2010, he could see something more needed to be done.

Hundreds of thousands of people were out of work, losing their homes, and the economy was on its knees.

“Homelessness in Greece is about people who have lost everything due to the economic circumstances,’’ he said.

“All of our vendors are victims of the socio-economic crisis, not mental health or drug abuse.’’

He said those who turned up seeking help who had issues such as substance abuse problems were referred on to other services for help.

Six years ago, Alefantis launched Shedia, written and edited by professional journalists, as a way of providing an income to the homeless men and women who sold it.

Shedia, which means Raft in English, now sells 25,000 copies a month in Athens and Thessaloniki in northern Greece.

The move saw Alefantis go from a volunteer organising a football team to working seven days a week running a multi-layered charity.

He named the charity Diogenes, for the Ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, who rejected all that was considered unnecessary in life such as personal possessions, and became homeless, living in an old wine cask in the markets of Athens.

The paper sells for four euros (equivalent to $6.30), of which vendors get to keep 1.52 euros. Shedia keeps 86 cents per edition for operating costs and the rest goes in government taxes.

The vendors will never get rich on paper sales, not even the highly-organised ones who can sometimes sell up to 300 a day. Many make only 10 or so euros a day.

But they have a purpose, and a way of interacting with a society that had forgotten about them.

“We discourage our vendors from accepting tips. If they really want to accept a tip of course they can, but if they went to buy a Herald Sun in Melbourne would they tip the newsagent? No,’’ Alefantis said.

“It is very crucial for us to establish very honest, transparent relationships with society.’’

More than 1.8 million copies of Shedia have been sold in the past six years by street vendors aged 18 years to 81 years.

The paper has generated $8.4 million for the struggling Greek economy.

“The figure that speaks most to the heart is 86.7 per cent of the vendors say they’re more confident about the future, and how to approach life’s difficulties,’’ Alefantis said.

“When they first walk through our door people often feel really defeated, they have lost trust in society, they’re suspicious of us.’’

He said he can physically see the transformation in vendors, who regain confidence through their new routines and purpose.

“I can see it happen, often after one day. It’s not just them making five or 10 euros a day.’’

“The most important thing is that sense of belonging again, the ‘I’m not invisible anymore, I go to an office’.

“They organise themselves.

“By the end of 2017, 93 of them (vendors) had found employment and left our network.

“When a vendor says ‘I am leaving, I found a job,’ there is a little party in the office. The vision is for Shedia to be shut down.’’

Alefantis’ charity helps their vendors put CVs together, coaches them on interviews and helps them apply for jobs.

To value-add to the paper business, he keeps all unsold copies of the magazine, and they are up-cycled into artwork and jewellery.

Vendors aged over 50 who find it particularly difficult to get back into the workforce are trained in craftwork, and the items made are sold in a shop the charity runs.

Ever-pragmatic, Alefantis decided the items must be attractive to all customers, and not just to buyers looking to help out the charity.

“Homeless vendors over 50 years of age now have a job,’’ he said.

“They have an official employee contract displayed in the shop as required by Greek law.’’

Always looking to make the world a better place, Diogenes has taken over an old heritage building in central Athens and embarked on an ambitious restoration process.

The ground floor is the new shop to sell the artwork, alongside the new cafe, bar and restaurant, while upstairs is the administration offices and distribution centre for the magazine.

Michelin-starred chef Lefteris Lazarou, a famous Greek chef and judge on the local version of MasterChef, is helping establish the cafe, which will provide hospitality training for the vendors, and another income stream for the charity.

The group also runs Invisible Tours, where homeless vendors take groups of paying tourists for walking tours around Athens, showing them other, more hidden sides of the city.

They share their stories with the tourists and schoolchildren and take them to places they would never see on the regular tourist trail.

Alefantis said it was a tour that did not take people to the Acropolis and other archaeological treasures but introduced them to “important social and solidarity institutions’’ such as soup kitchens, day centres, drug rehabilitation centres and homeless shelters.

“From the visitor’s perspective, it is a unique opportunity to get acquainted with and to listen to a very personal, human story that to many will sound very familiar, too close to home,’’ he said.

The Greek economy crisis bit hard eight years ago when the world lending markets stopped giving loans, concerned about the country’s ballooning budget deficit, debt and bulging welfare bill. Debt was 180 per cent of GDP.

The economy shrunk by 26 per cent and the impact has been likened to the scale of the Great Depression in the US in the 1930s.

The country of 11 million people has largely been living off EU loans since that time, although is just now slowly emerging from the slump.

But the damage has been done — hundreds of thousands of jobs disappeared, and 20 per cent of working-age Greeks are long-term unemployed compared with 6 per cent across the EU.

Many cannot access their pension because they did not work the required number of years.

And a lack of social welfare nets meant some people simply had nowhere to turn — meaning organisations like Diogenes stepped into the breach.

One in five of the people the charity helps are women.

One of them, Christiane, 61, started as a paper seller, then learned how to make jewellery and craft from the old copies of Shedia.

She now works in the shop, selling the items she and others have made.

French-born, she came to Greece in 1979, and found herself in need of help after her life spiralled out of control.

“I was married, divorced, I had a child, I lost my child, drug use, I went to jail,’’ she said.

“I went to Shedia and they helped me.’’

Christiane was put in contact with Alefantis’ charity as part of a court-mandated program to stay off drugs.

“The therapy helped me stand on my own feet,’’ she said.

She started in 2015, first selling the papers, then being taught how to make the jewellery, then working in the shop.

“I needed someone to lean on and Shedia was my shoulder to lean on,’’ she said.

Fluent in French, Greek and English, she is a natural in the shop and dealing with customers but prefers making the jewellery to selling it.

“I feel funny to say goodbye to something that has taken many hours to make. Nice, but sad,’’ she said.

Originally published as Shedia magazine: How Christos ‘Chris’ Alefantis is lifting Athens’ homeless out of the streets