Scientists say Australia will play key roles in coronavirus vaccine

It took 15 years to get the incredibly successful cervical cancer vaccine to market, but the Australian immunologist behind that medical marvel says we can beat COVID-19 much faster.

NSW Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Blood, sweat and tears in race for a coronavirus cure

- Crack squads of scientists developing 70 vaccines

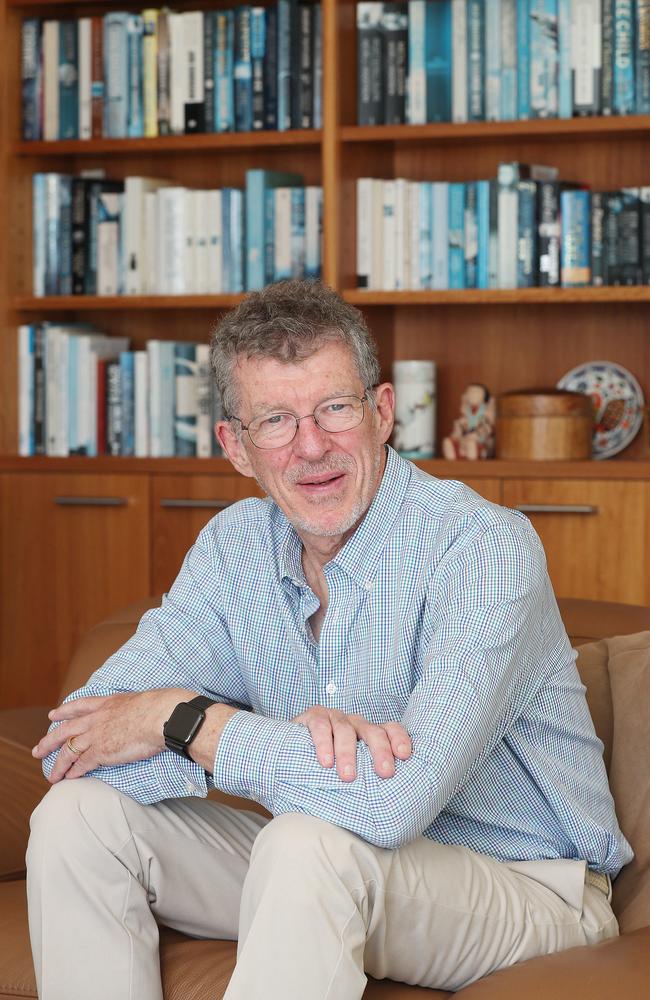

When world-renowned Australian immunologist Professor Ian Frazer made his breakthrough discovery of a vaccine preventing cervical cancer, it took 15 years to get it to market.

Luckily he doesn’t believe a COVID-19 vaccine will take that long, estimating it will be a year to 18 months.

His vaccine has been a remarkable success story, with millions of schoolgirls and boys jabbed every year and deadly cervical cancer rates cut by almost 80 per cent.

The eminent scientist, a former Australian of the Year, said most Australians could be exposed to the coronavirus, although it’s also possible the COVID-19 bug could significantly weaken and become less deadly.

MORE CORONAVIRUS NEWS

NSW’s strict rules have spared 700 lives, leaked data reveals

Coronavirus mask shipment brings elective surgery hope

Abuse, spit or cough at any worker and cop a $5K fine

Back when he and his team were working on the human papillomavirus — the virus that causes cervical cancer — they were one of the first to engineer a non-infectious synthetic vaccine by conducting genetic sequencing.

“We can now plan to make vaccines by means which simply weren’t possible even 20 years ago, where basically there were only two ways of making a vaccine that were accepted,” he said.

“One was you took a virus and killed it and used that as the vaccine.

“The other way was we tried to make it less strong in the lab, by growing it repeatedly, and that made it so that it couldn’t cause disease.

“Now we can actually work from the molecular building blocks of the virus.

“We work out what it’s made of and we can make the proteins artificially in the lab using genetic engineering technologies.

“We have new tools at our disposal, which are certainly a lot quicker than the old ways of doing things.”

He is optimistic about the research being carried out for a vaccine at the University of Queensland — one of many teams around the nation racing to find a breakthrough — because they are using a new technology of “molecular clamping”.

This allows the scientists to assemble a part of the virus protein in the lab and keep it in the right 3D shape, increasing their chances of success.

“I think that there’ll be a number of groups will get to the point where they’ve got to do vaccines fairly quickly, including the group in Queensland and some groups in America,” he said.

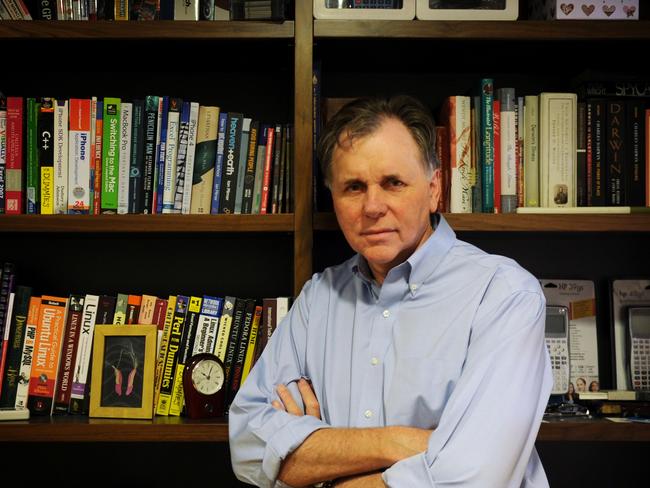

Another eminent Australian scientist, Nobel prize winner Barry Marshall, who defied medical conventions by deliberately infecting himself with the helicobacter pylori bug to prove it caused ulcers and could be treated with antibiotics, said vaccines usually required an enormous amount of research and approvals along the way.

But he said many bureaucratic hurdles are being streamlined during this current crisis.

“Several steps (to manufacture) take time,” he said.

“In between each step may be several months of delay by the bureaucrats and regulators who work on a schedule and usually allocate a number of days to respond.

“For example, I believe that any genetic modified medical product (biological medicines such as vaccines) take about 200 working days for our gene regulator.

“In COVID times these people fast-track applications and probably can do it in two to four weeks.

“An amazing amount of biosecurity documentation is going on for something like COVID-19.

“It’s very tiring and is not really fundamental research — but it does need to be done properly.”

Finding a vaccine is not certain, warn the experts, particularly because most vaccines work on bloodborne viruses and the coronavirus affects the lungs and airways.

But, in the meantime, one of the other promising medical treatments could be the use of serum plasma from the blood of recovered patients, which contain natural antibodies that have learnt how to fight the virus.

“It’s proven technology, we now know people who are immune and have antibodies,” Professor Frazer said.

“Testing whether the serum can control infection is relatively easy in comparison to all the other things we’d like to try.”

He pointed out that Australia’s blood banks had the capacity to make serum from blood plasma already and the CSL is one of the world leaders in that field.

“We are very fortunate we have in Australia a manufacturing capacity to make serum in large amounts, which might turn out to be quite lifesaving,” he said.

Professor Frazer said this coronavirus crisis would become a catalyst for better planning for epidemics in the future.

He said younger generations had never had to deal with the horror of deadly infectious diseases and we have collectively forgotten the devastation they cause.

“I think that’s perhaps one of the reasons why people have been reluctant to accept the need for social distancing is people don’t die of infection any more,” he said.

“We live long, healthy lives and yes, we may get chronic disease when we get old.

“But the concept of getting serious infections which kill off large numbers of people — which happened regularly before vaccines were available — is unthinkable.

“Yet if you go out to any of the graveyards in western Queensland and look at the ages of the kids died, you’ll see that the Victorian-era families would have had eight or 10 kids and most of them died before the age of 10 of infectious diseases.

“Ideally, we want to be ready for something like this earlier in the epidemic — it’s better to try to put the fire out before you discover the fire is already burning the house down.”

Director of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS)

Professor Kristine Macartney said the race towards a coronavirus vaccine would completely change the way clinical trials were conducted.

“We’ve had new ways of running clinical trials where you do a lot of steps in parallel as opposed to one after the other. We are looking at things like adaptive clinical trials and new ways of examining data,” she said.

“We used to do a step, then wait and analyse, but now we are saying can we go in and analyse the data earlier? Can we start to build manufacturing capability even before we know which vaccine will be the vaccine of choice?”

Prof Macartney said it was crucial to balance time with effectiveness when it came to finding a cure.

“To date the progress towards the development of a vaccine has been absolutely incredible. We’ve seen an amazing global effort in time-frames that are completely unprecedented than anything that’s come before us. Vaccine development usually takes decades,” she said.

“Even in ebola and zika vaccines we’ve seen rapid vaccine development then but the time frames here have been absolutely incredible. The world is doing its very best.

“We need to carefully evaluate every vaccine we use in humans for safety and impact.”

Prof Macartney, who has a background in specialising in the rotavirus vaccine and influenza vaccine, said it was also important to consider how the vaccination would be delivered.

“Once we have vaccines that are promising, those vaccines still have to be manufactured at scale and rapidly deployed,” she said.