Why Alcoa finally wants to clean up its Aussie partner Alumina

With more of the financial spoils going to Alcoa and a skinny premium, the hardened ex-WMC shareholders could still put up a fight.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Is the last piece of the WMC empire about to be swallowed up?

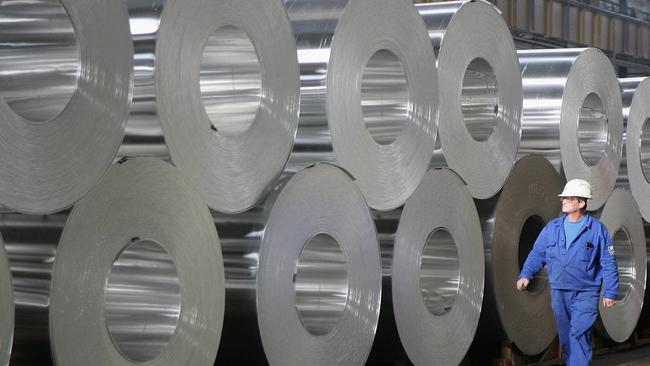

Pittsburgh metals major Alcoa is pulling the trigger on a $3.4bn move on Alumina, its minority Australian partner it shares in a string of smelting and mining operations in Australia, including the aluminium smelter in Portland, Victoria.

This is a buyout that is more than two decades in the making, and today Alumina represents a quirky cul-de-sac of corporate Australia.

However, with more of the financial spoils going to Alcoa, including $500m of franking credits than the Australian investors and a skinny premium under the all-share deal, there’s no certainty the Alumina side street will be finally closed off.

Alumina emerged as the remaining listed rump of WMC that later saw BHP snap up the Olympic Dam and Nickel West assets for nearly $10bn in 2005.

In a broad arc of business, it was an approach from Alcoa several years earlier that got the ball rolling on WMC’s big split.

In 2001 amid a commodities prices slump, the cash-strapped WMC and its then boss Hugh Morgan saw its long-time partner Alcoa as a way to raise some funds. The US company’s then chief Alain Belda flew to Australia and met with the WMC board. He blindsided the Australian miner by making a bid for the entire business copper and all. This pushed Morgan to reluctantly split off the aluminium assets from the copper, nickel and fertiliser business. Morgan was convinced Alcoa’s spurned Belda would return with an offer for the newly listed aluminium business – but nothing materialised.

In a banking footnote, WMC’s 2001 adviser Tony Burgess, then with Deutsche Bank, continues to advise Alumina today through Flagstaff Partners.

Listed postbox

The ASX-listed Alumina continues to be the 40 per cent owner of Alcoa World Alumina and Chemicals joint venture, with US major Alcoa the majority partner and operator.

AWAC in turn owns a string of assets including the Kwinana refinery in Western Australia and several bauxite mines. It owns refineries and mines in Spain (San Ciprian), the Middle East and Brazil. AWAC is also the 55 per cent owner of Victoria’s Portland plant, which also includes Chinese and Japanese partners.

Since its listing, Alumina was always seen as nothing more than a postbox in Melbourne’s Southbank for AWAC to send its dividends and in turn the passive Australian company would distribute the cash out to shareholders.

The messy ownership structure has made many headaches for Alcoa – including a bitter court battle that led to a rewriting of the “green book” that governed the rules of the venture, including the level of dividends that would come out.

Strategic and policy decisions around AWAC were also slowed down through the need to regularly have them signed off by Alumina through a strategic council.

Still, this arrangement continued on for almost two decades, so the question is why is Alcoa moving now?

A key change last year had swung the balance in the way that Aloca viewed its long-term Australian partner.

A surge in European energy costs prompted AWAC to first curtail production at the San Ciprian refinery and then later the Kwinana refinery in WA. These two decisions resulted in a huge cash call on AWAC. At the same time, there are plans to expand bauxite mines in WA, although a lapse of mining leases means for now it is contained to extracting lower-grade ore that comes at a cost.

AWAC was moving from a net cash generator for Alumina to a business that needed cash injections, and there is limited balance sheet capacity for ASX-listed Alumina to support this. Last year alone, Alumina injected nearly $200m into AWAC, representing its share of the working capital needed to support AWAC and to help pay for distributions.

Already, Alumina’s net debt position has moved to nearly $300m, which is closing in on its $500m debt ceiling. The rise in borrowings comes at a time when financing costs are surging. With the debt pushing up, it is likely that Alumina is likely to strongly push for more of the cash flows of the business to be used to pay distributions, over reinvesting back into growth.

Portland looms

It is telling that Alumina’s independent board members under Peter Day have endorsed the deal that stands to deliver Alumina shareholders 31 per cent of Alcoa following the merger.

This suggests more needs to be done in cleaning up AWAC’s WA assets as well as its long-troubled Spanish plant, and there could be a lumpy investment period in the slender chance Portland remains open beyond the expiry of its current energy deal in 2026.

There are big question marks over Portland, the plant which uses nearly a quarter of the state’s electricity generation, and has previously been slated for closure and efforts for a sale.

Fund manager Allan Gray has already supported the deal with its 19.9 per cent share in Alumina.

Citic, which hasn’t indicated how it intends to vote its 20 per cent Alumina stake, holds the fate of the deal. A third investor, fund manager Schroders, holds a little over 6 per cent of the ASX company.

From Alcoa’s side, the buyout represents a long overdue clean-up, giving it cost savings as well as speeding up strategic and financial decisions as well as the full cashflows of AWAC. Last year, it generated nearly $740m in cash flow. The relative size shows Alcoa, at the equivalent of $7.3bn, is not much bigger than its target.

Earlier Monday, Alcoa chief Bill Oplinger said: “When investors look at the structure, they don’t always understand it. And it can be complex.”

There are serious tax benefits too, with Alcoa inheriting a pool of nearly $500m in franking credits that are only available to Australian shareholders. These will stay with the new entity which in turn will be owned by the 31 per cent Alumina shareholders.

Finally there’s the share price gains. AWAC is more leveraged to the recovery in alumina prices. Since the announcement that Kwinana and San Ciprian’s output is being turned off, Alumina’s shares have climbed nearly 40 per cent. Alcoa’s are up only 6 per cent and the US company clearly wants to capture more of that upside.

Alumina investors – many who have stayed on from the WMC days – now need to weigh-up if after two decades whether the slender 13 per cent premium is finally worth getting up and leaving their comfortable cul-de-sac for.

–

Suncorp’s new era

With Suncorp’s banking arm now on track to be sold to ANZ for $4.9bn in coming months, Australia’s great experiment in bancassurance is over.

Suncorp emerged out of a global push from the late 1990s that lasted until the global financial crisis that viewed banks and insurers as offering a one-stop shop to the same customer. Here it was seen that a bank could seamlessly sell a home loan, just as much as a life insurance policy or home and contents insurance.

The advantage for banks was the “assurance” part was capital light so this allowed them push for profit without the need for heavy investment.

Suncorp was stitched together in the late 1990s as the benchmark of bancassurance by Queensland’s then Borbidge government. This saw the combination of three state-owned businesses of insurance, banking and rural-based and business lending, under one roof to become Suncorp.

However, like most things pushed up from the states, parochialism is never far away with the real aim to have a national champion with the balance sheet heft that could take on the big four from the southern states.

Suncorp chief executive Steve Johnston, who in the mid-1990s was an adviser to former Queensland premier Rob Borbidge, says he hasn’t used the term bancassurance for years, with the 2018 Hayne royal commission largely ending the business model. Cross-selling and commissions were widely regarded as the reason behind banks treating customers badly. The big banks have since offloaded their wealth businesses and exited everything non-core to banking.

“I don’t know that there’s many standout exemplars of having achieved the true elements of bancassurance,” Johnston tells The Australian.

“To the extent that it was challenging and complex previously, the royal commission and the anti-hawking rules have made it even more complex and challenging,” Johnston says. He points outs with insurance as Suncorp’s dominant business it makes it harder to reverse sell insurance back into a bank.

Johnston was talking for the first time since the Australian Competition Tribunal last week gave the green light for Suncorp to sell its bank to ANZ. It follows a long-running regulatory process where the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission attempted to block the deal. However, this ruling was comprehensively overturned on appeal.

The deal still needs the Queensland government to change the Suncorp legislation (state Treasurer Cameron Dick has supported the deal). Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers, a Queenslander, has the final say in the sale. The sale is expected to be finalised around the middle of the year and the bulk of the proceeds will be returned to shareholders.

Johnston admits to some frustration about the length of time of the regulatory process but quickly adds he needs to put this aside because it doesn’t get him anywhere.

Suncorp’s December half results underpinned Johnston’s motivation to become a pure-play insurer. Cash earnings for the half were up 13 per cent to $660m, underpinned by a surge in earnings across consumer insurance. Price rises across policies and growth in market share back the returns. Suncorp’s bank, however, saw earnings drop 25 per cent to $192m as margins were crunched on higher funding costs. As a bank with a smaller deposit book it has to pay up more for costly funds.

The rationale to exit banking remains unchanged, the Suncorp boss says.

“I firmly believe the more that we can focus the whole organisation on delivering improved insurance products – which is what we’re good at and we’ve demonstrated we’re good at it – and reduce the reliance on things that we’re less good at, the better a business we will become,” he says. Suncorp shares ended up 3.5 per cent.

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

Originally published as Why Alcoa finally wants to clean up its Aussie partner Alumina