Covid stimulus boom could be about to lead to a bust

After a “prosperous pandemic”, the reality for Australia looks set to hit – and our biggest weakness is about to be exposed.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When the pandemic first arrived on Australia’s shores, Prime Minister Scott Morrison promised that the federal government would provide a bridge back to where the economy was prior to Covid-19.

Looking back, late 2019 seems like a bygone era in some ways. No virus, no running political battles between the states and an Australia united by the challenges of the worst bushfire season in years.

But when you look back on the economy of late 2019, it’s quite a different story.

Rather than seeing an economy on the cusp of another year of strong growth, the various indicators at the time suggested that Australia was facing a major economic slowdown.

Yet in a stroke of ironic luck that we have almost come to expect from the Aussie economy, a $507 billion in stimulus the pandemic prompted saved the economy from a year of lacklustre growth and perhaps even a recession.

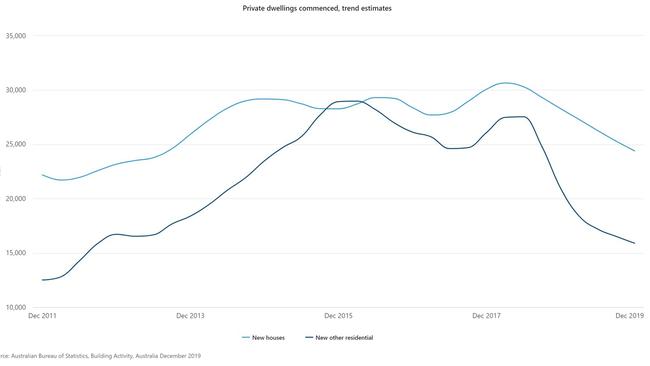

In October 2019, a paper authored by the Reserve Bank (RBA) warned that the housing construction boom was coming to an end.

After five years of strong growth, the housing construction boom had finally run out of gas, particularly in the apartment and unit building sector.

In March 2018, 30,797 houses and 29,111 units/apartments commenced construction.

By the time the RBA paper was authored a little over 18 months later, the number of houses commencing construction was down 19.1 per cent, with unit/apartment construction starts down 45.3 per cent.

With a large number of builds expected to be completed during 2020 and a lack of new projects commencing construction, it was clear that there was going to be some pain for the economy and the construction sector.

In the RBA’s paper it concluded that the decrease in construction activity would directly decrease GDP growth by 1 per cent and have a “somewhat larger” than 1 per cent decline due to the impact on associated industries.

In the fourth quarter of 2019, the economy grew by just 2.2 per cent over the course of the year.

With the population growing by 1.5 per cent over the same period, 0.7 per cent growth after accounting for population growth was not an impressive outcome.

In July 2019, UBS senior economist George Tharenou warned that it was expected that construction investment would fall by 10 per cent.

“Our tracking of construction job ads is consistent with 100,000 job losses ahead,” Tharenou said.

In reality, instead of 100,000 jobs being lost, the construction sector boomed on the back of government stimulus programs such as HomeBuilder and various state government new home grants.

Meanwhile, in the labour market, things were less than stellar despite a relatively average year in terms of overall job creation.

In the fourth quarter of 2018, private sector jobs growth came to an abrupt halt and public sector jobs growth took over almost entirely.

A little reminder that prior to the pandemic Aussie private sector jobs growth was flatlining and the vast majority of new jobs being created were by the public sector.

— Avid Commentator 🇦🇺 (@AvidCommentator) December 2, 2021

In some ways the pandemic saved us from having to deal with the consequences of this weak jobs market. pic.twitter.com/feks0T08ES

At the outset of 2020 the Aussie economy was in a challenging place, the construction industry was set to slow, private enterprises weren’t especially keen on hiring and the nation was coming to grips with the aftermath of a devastating bushfire season.

In early January 2020, AMP Chief Economist Shane Oliver predicted that the bushfires would subtract 0.4 per cent off Q1 GDP, as the impact on affected areas and the broader economy became clear.

Between all these various factors, it was clear that the Australian economy faced a challenging 2020 even before the virus arrived on our shores.

But we know now that this was not to be. Instead, Australians have faced a very different series of challenges, but ironically the majority of people have enjoyed a remarkably prosperous pandemic.

I bet you never thought you would have read those words together two years ago.

In late 2019, Australia’s economic growth cycle was arguably coming to an end, as the various booms supporting the economy faded and we were left with a heavily public sector supported job market and headline growth majority driven solely by population growth.

Like so many other strokes of luck over the past 30 years, Australia never saw the end of that particular boom, instead a stimulus commitment by the Morrison government of over half a trillion dollars created an entirely new boom on top of the faltering old one.

This unprecedented cash splash bought Australia a great deal of time, but the question is how much?

Is this the beginning of an entirely new economic cycle that has years of strong growth yet to come, or is it merely a protracted sugar hit that will fade and leave us more vulnerable than we were when we began this journey?

The simple truth is we don’t know. We are in truly uncharted waters, and there are no signposts or landmarks to help guide us.

The Morrison government’s stimulus programs created an enormous economic boom which has left some Australians with more work than they could ever possibly do.

But ultimately, most huge booms eventually end in some form of correction as the economy regains its equilibrium and things return to normality.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as Covid stimulus boom could be about to lead to a bust