Casino giant Star Entertainment facing a bleak future

For a business which makes its money through gambling, there have been no winners from Star Entertainment’s fall from grace and now it faces the real possibility of going bust.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When you’re in the casino game you can go from winner to loser in a blink of an eye, but Star Entertainment’s plunge into the financial abyss has been a long time coming.

From a seemingly impregnable position in the years before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, Australia’s largest casino operator is now facing insolvency, hit by a wave of crises – much of its own making. Billions of dollars have been stripped from the ASX-listed company’s value as the stock, which peaked above $5.40 in 2018, slumped to a record low of 10c this month, valuing Star at just $287m.

On Monday as it released its December cash flow report, Star warned there is “material uncertainty” it can continue operating.

The Australian also revealed that the cash-strapped casino operator has already received millions of dollars worth of secretive tax deferrals from the Queensland government.

Queensland’s revenue office deferred $9.6m worth of Star’s gaming and payroll tax liabilities last year, under “standard hardship processes”. The former state Labor government then went into negotiations in September for a larger financial lifeline, and offered Star a 12-month tax deferral, capped at $100m. The deal, which fell through, was contingent on the company guaranteeing the retention of a minimum number of full-time equivalent employees across its Queensland operations and halting any incentives or performance bonuses for executives.

Under-siege Star CEO Steve McCann has been locked in a war room with financiers, his board and lawyers as they explore a possible way out of the financial quagmire.

Star revealed earlier this month that it had burnt through more than $100m in three months and on Monday said its cash at hand at the end of December was $78m.

“While discussions continue with respect to a range of different solutions, there is no certainty that any of these negotiations will … increase the group’s liquidity position,” Star said. “In the absence of one or more of those arrangements, there remains material uncertainty as to the group’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

McCann has gone cap in hand to the NSW and Queensland governments looking for a financial lifeline to stave off insolvency. He wants a temporary pause on the payment of gaming taxes to help protect jobs and tourism across the two states.

“We need more time,” McCann said on Friday.

NSW Premier Chris Minns over the weekend was adamant that there would be no more government assistance, after a deal last year in which Star pledged to maintain more than 3000 jobs in NSW until 2030.

Queensland Premier David Crisafulli has left the door ajar, saying his government would “consider any requests that come forward”.

“My support is for the workers (and) making sure that the casino (Queen’s Wharf) continues to operate,” he said. “I am not interested in the bottom line of Star.”

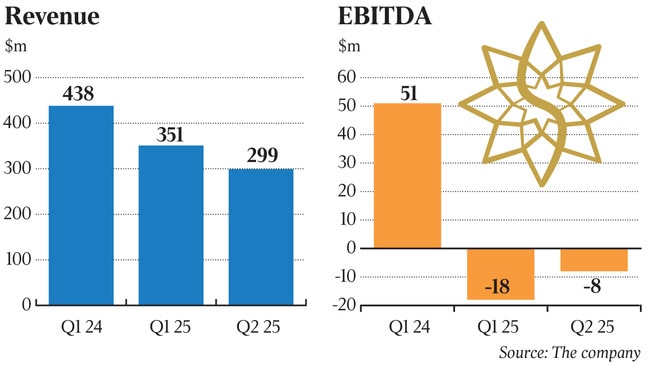

Star’s revenue fell 15 per cent to $299m in the December quarter, even as it narrowed its losses to $8m from $18m.“There is continued weakness in the operating performance of the group due to the ongoing challenging consumer environment, the impact of mandatory carded play and cash limits in NSW as well as costs associated with ongoing remediation activities,” the company said.

The main players

The recent rock bottom share price has also prompted secretive Macau businessman Wang Xingchun to stump up just $30m over recent months to secure a 6.52 per cent stake in Star, emerging recently as the second-biggest shareholder behind pub baron Bruce Mathieson, who spent considerably more building his 9.52 per cent holding.

The pair will want a seat at the table if the group – which has casinos in Sydney, Brisbane and the Gold Coast and employs up to 9000 workers – is broken up or goes bust, which is looking increasingly likely.

“We now incorporate a 50 per cent probability that Star falls into administration, and equity holders are wiped out,” Morningstar analyst Angus Hewitt has said.

Market speculation is that US private equity giant Blackstone, owner of Crown, could have its eye on the Sydney business, while the Gold Coast operation would be a natural fit for Mathieson, and Malaysia’s Genting Group might target Brisbane assets, where Star and its JV partners Far East Consortium and Chow Tai Fook Enterprises last year opened the $3.9bn Queen’s Wharf project.

“It either goes bankrupt or someone buys it,” Mathieson has said of Star’s prospects.

Wang, rumoured to have links to the controversial Hong Kong-based joint venture partners that own half of Queen’s Wharf, no doubt also has an end game.

If Star goes into administration, its shares will be worthless, thousands of jobs will be at risk, and only someone who has passed lengthy probity checks will be able to hold the casino licences, which will limit potential buyers.

The United Workers Union has been in discussions with the company and the NSW and Queensland governments advocating for support for Star’s staff.

“More concrete measures are needed to ensure the long-term stability of jobs and the company’s operations,” union director Andrew Jones said.

Angry Star staff have lashed out at the salaries and bonuses being paid to executives of the troubled group.

Queensland-based staff, in an email, said that while they struggled to make ends meet, Star’s executives enjoyed “massive salaries and bonuses”.

“For years, employees at The Star Brisbane (previously Treasury Brisbane) have endured low wages, with pay far below what staff at other casinos across Australia receive,” they said. “Sporadic, insignificant pay rises have done little to address the rising cost of living, leaving us feeling undervalued and disillusioned.”

Burning through cash

Talk of Star’s imminent demise was triggered when the company delivered a shock market update on January 8, stating its cash reserves had sunk to $79m at the end of 2024.

Star burned through nearly half its $179m cash reserves in the December quarter and could run out of cash by the end February.

The company has already used the entire $100m loan offered to it by a banking consortium last year, and it’s struggling to meet stringent conditions so it can draw down on another $100m. Star has about $1.6bn in debt for Queen’s Wharf that needs to be refinanced by December 2025.

Star’s plight follows a series of damning public inquiries that concluded the company is unsuited to hold a licence as it turned a blind eye to the risk of money laundering and other criminal activities.

How did things go so pear-shaped?

Huge cost overruns on the Queen’s Wharf precinct and Covid lockdowns played their part in bringing Star to its current crisis. But the brutal truth is that tighter regulations to prevent money laundering and other criminal activities, as well as a poor corporate culture, has resulted in a broken business model.

The rivers of gold previously enjoyed by Star as it attracted highrollers from around the world have dried up, leaving it scrambling to find a replacement for lost revenue to pay down mountains of debt and huge fines.

There had been rumblings about Star going back to Matt Bekier’s eight-year tenure as chief executive. In 2021, media exposes revealed Star management had been warned that its anti-money-laundering controls were inadequate. They claimed that between 2014 and 2021 Star had attempted to recruit high-rollers who were allegedly linked to criminal or foreign-influence activities.

‘Deceptive process’

A year later a public inquiry in NSW chaired by Adam Bell SC found the gaming giant had set up an “inherently deceptive and unethical process” disguising more than $900m as hotel expenses to allow wealthy Chinese gamblers to bet at the venues, failed to check the source of the money – and knew for years it was in breach of the rules.

Bell’s report said that instead of shutting down the junkets bringing in major overseas gamblers, as Star should have, it allowed them to continue to operate, “a collective decision by the senior management … which reflected a culture in which business goals were given undue priority over regulatory and money-laundering and terrorism financing risks”.

The company was fined $100m, its gambling licence suspended and operations placed under the control of a regulator-appointed manager, Nick Weeks. Weeks also took control of the Queensland casino licences after an independent review found Star had misled regulators in the state and failed in its anti-money-laundering duties. It was hit with another $100m penalty.

Bekier fell on his sword in April 2022 and was replaced on an interim basis by chairman and former Australian Rugby Union CEO John O’Neill, who announced his own resignation in a matter of weeks.

The pair are among 11 former Star directors and executives due to face Federal Court in February in a civil case launched by the Australian Securities & Investments Commission over their alleged failure to “give sufficient focus to the risk of money laundering and criminal associations”.

Hopes that new management would restore Star’s lustre were short-lived. Star under CEO Robbie Cooke, who replaced Bekier in 2022, continued to come under the regulatory spotlight. Cooke was forced out in early 2024 and replaced by McCann, who negotiated a $10m salary package when he signed up for the CEO challenge.

A second Bell inquiry last year found that Star’s problems had persisted.

Star has set aside $150m in cash, in case it has to pay fines over separate action taken against it by federal money-laundering regulator, Austrac. According to some analysts, that could exceed $300m.

Star also needs to pay another $10m of a $15m fine imposed on it in October by the powerful NSW Independent Casino Commission as a result of the Bell II inquiry, as well as pay for a new round of expensive legal and consulting fees from more recommendations.

Cash-strapped Star has now been forced to embark on a series of asset sales to raise money, but its only major sale so far has been the leasehold of the heritage-listed Treasury Casino building in Brisbane to Griffith University for $67.5m.

It has failed to sell the nearby Treasury hotel and carpark, even as McCann has signalled that other assets may have to be offloaded, including the Darling hotel properties on the Gold Coast and in Sydney, as well as car parks and an event centre in Sydney.

As its debts and fines mounted, Star has been stymied in Sydney by the mandatory introduction of carded play to stop money laundering and encourage responsible gambling.

Since carded play was rolled out in Sydney, Star had seen revenue slump 15.5 per cent compared to the period prior to its introduction. Patrons can no longer simply walk into a casino from the street and exchange a wad of cash for chips or tokens.

The new rules mean patrons have to prove their identity and fill out a detailed questionnaire about the source of their finances before taking a seat at a poker machine or card table. Players also are now limited to $5000 daily limits, which will fall to $1000 a day later this year. With the tables empty, cash reserves dwindling and the insolvency hawks circling, Star is running out of opportunities for another roll of the dice.

More Coverage

Originally published as Casino giant Star Entertainment facing a bleak future