IT had been a late night of serious conversation for Richard Randall and his wife.

It was past midnight, and outside their front door a thick winter fog had settled like a shroud over the town of Childers.

“From this point on, I’m going to look at quitting,” he’d said to her.

This part-time firefighting job, which some mistook for his full-time job, was consuming their lives.

They both worked at the school, had four young children.

His wife would take the pager with her if she went into town, knowing that she’d need to rush home and take over with the kids if it went off.

It sounded its alarm now, in protest of their discussion.

He hadn’t quit yet, so he got to his feet and ran out the door.

It was just after 12.30am and Lieutenant Richard Randall, officer in charge of Childers Fire Station, was a 15 second sprint from home to truck.

He belted over bitumen, running headlong into the dark, into fog, the first of his crew to arrive.

On a normal night, if he’d turned his head, he would have seen it.

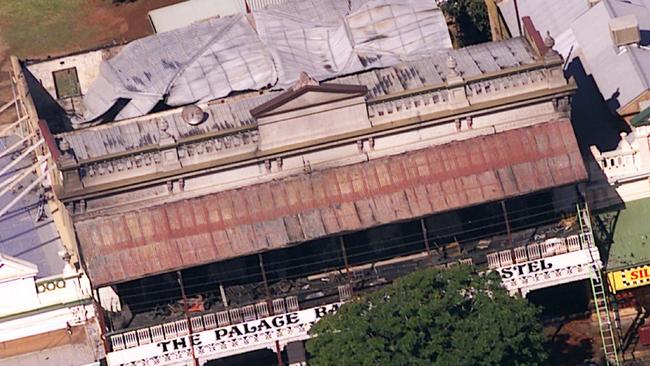

The Palace Backpackers Hostel – just 50m away from his home – was on fire. That’s what his pager had said. That’s what the Firecom operator would tell him.

He hadn’t needed to look. And maybe it would have done no good. The fog was thick. And anyway, he could smell that fire.

At his house, the phone was ringing. They had rural fire phones back then. His wife picked up.

“Is it true?” someone asked. “Is the backpackers’ on fire?”

She ran into the street and stared through the fog at the glow of one of Queensland’s most deadly fires.

‘IT WAS BLOODY GOING’

COL Santacaterina – or Curl to everyone who knows him – was a train driver by trade and a firefighter by passion.

His first fire was more of an unofficial one. He hadn’t known he was a firefighter until he and a mate spotted a shed ablaze.

There’d been nobody around.

So they’d “commandeered” the local fire truck and tried their best to get water out of it. They’d worked it out in the end. But things hadn’t ended too well for the shed.

He’d joined the auxiliary – or part-time – brigade after that.

Back in the day they’d turned out in thongs and shorts. No radios. Fighting fires all day and night with no way of anyone knowing if they were alive or dead.

“And then we got overalls and gumboots and we thought we were just bloody it,” he said.

In 2000, Santacatarina and his wife lived out near the hospital.

The station was a minute or two by car, the route taking him past the Palace.

His pager had woken him that night and he’d jumped into his ute in his pyjamas, no clue what time it was.

He’d glanced at the backpackers’ as he drove by on the way to the station. Saw nothing but fog. The fire, at that point, was at the back of the old building.

“All I could see was some people out on the footpath. And I thought, hello, they’re going to work, or a bus has come in and dropped them off,” Santacaterina said.

“I couldn’t see nothing, so I thought, it can’t be much.”

They had a crew of four. Randall, Santacaterina, Robert Winkleman and Hayden Whitaker. The first triple-0 call had come through at 12.32am. Randall’s crew were out the front of the Palace, blocking half the Bruce Highway, six minutes later.

Only minutes had gone by since Santacatarina had peered through the fog as he’d driven by. And everything had changed.

“It was bloody going,” he said.

A TRUCK RUMBLES PAST:

SERGEANT Geoff Fay had arrived in town 18 months earlier. It had been a four-officer station in those days. No nightshift.

The master bedroom in the police residence was at the front of the house. Sometime after midnight a truck rumbled to a stop outside his window.

He peered out to see the fire appliance collecting a crew member. His neighbour across the road was in the local brigade.

Somewhere inside his house a phone started ringing.

TWENTY BACKPACKERS HUDDLED ON A ROOF

APPLIANCE 913 from Childers Station and its on-call crew made a quick assessment from the edge of the Bruce Hwy.

Randall called it through to the Firecom operator. Code 99. Building well involved. They’d need more crews on scene.

Thick black smoke was pouring out from under the veranda, from the building’s side windows.

An orange glow was coming from inside. Backpackers were huddled on the footpath or stranded on the awnings of the adjoining butcher’s shop.

Santacaterina helped Whitaker throw a ladder up to get the backpackers down to safety. There were 20 or so on top of the butcher’s.

“Get them down,” he yelled, and took off to get into his breathing apparatus. It would be up to he and Winkleman to enter the burning building.

FIRE FLASH ‘NEARLY BLEW US OUT THE DOOR’

THEY went in through the front doors with a hose. No time to tap a hydrant, so they would use water from the truck – a couple of minutes worth at best – to get things started.

There were people inside on the ground floor. Shocked. Walking in circles. Santacaterina and Winkleman got them out.

They put the hose on it. The fire roared back.

“Then Richard told us to get out because it was going to flash over,” Santacaterina said.

“And then there was a big gust of wind. Just about blew us out the door.”

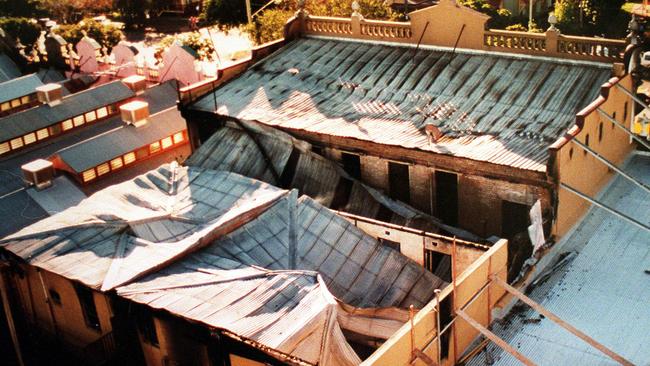

The “wind” was the fire flashing over. Super-heated. A build up of heat in the building’s atrium area that had caused the sudden combustion of the upper floor.

It was a roar. An explosion.

They hadn’t had time to think yet about who might have been up there.

“Our truck was parked on the Bruce Highway, probably 35 to 40m away and it melted our flashing lights on top, melted them,” Santacaterina said.

“On the front seat, we had a new truck, only a week old. It still had the new plastic covers over the seats. Melted them to the seat.”

Randall felt it. Understood what it meant.

Another crew had arrived by then. He’d sent them out the back. Later, they’d tell him one of the backpackers who’d escaped had run back in. They’d tried to stop him. He wouldn’t make it out.

“You just know … when it flashes over like that, the temperature is 1000 degrees. No-one is living through that,” Randall said.

He had so many things to do. Above him, powerlines were arcing and cracking. The noise was everywhere and it was nowhere. He blocked it out to focus on the fire. Winkleman ran at him, shouting.

The aluminium railing had liquefied from the heat. Molten metal ran down the back of his coat.

Randall flicked it off before it burned through.

A frantic backpacker approached him.

“My friend is inside,” he said. “Upstairs.”

“Yes mate,” Randall told him. “We’re trying to do something about it.”

There was nothing they could do about it. Anyone inside that building would be dead.

BURNING BODY FALLS THROUGH CEILING

JOHN Watson’s pager was an incessant beep that had been plaguing him all week. He was the Area Director, based in Bundaberg, and an alert on his pager meant a serious incident.

“We should just put the pager in the freezer and forget about it,” his wife had joked earlier that night.

They’d been woken up at odd hours a lot. And again that night. A little after 12.30am.

It always gave him a jolt, that beep-beep-beep that could not be ignored.

He got up and called Firecom as he headed out to his work car.

A sedan with emergency decals. Lights and sirens. There was a fire at the backpackers on the Childers main street. A bad fire.

It was a 30-minute drive and no easy drive that night.

The fog was thick. He had trouble following the white lines.

“It was an old pub that had been converted into an accommodation building,” Watson, who would go on to become the QFES’ Assistant Commissioner, said.

“So, my knowledge of the Palace was … it had a lot of backpackers in it and that was quite a high life risk for us. It was quite a level of urgency for us that night.”

Randall briefed him. They were fighting the fire at the building’s rear at that point. The upper floor had flashed over.

It was an inferno. There were flames exploding from the top of the building.

Police had arrived on scene and were talking to stunned backpackers wrapped in sheets and blankets about who might be missing.

Randall had told him there could still be people up there.

There was nothing they could do but keep working to put the fire out. Dread. Watson felt nothing but dread.

He spoke to the hostel’s operators. He wanted their records, their fire and evacuation plan. They’d pulled Santacaterina and Whitaker out but now a team needed to go back in.

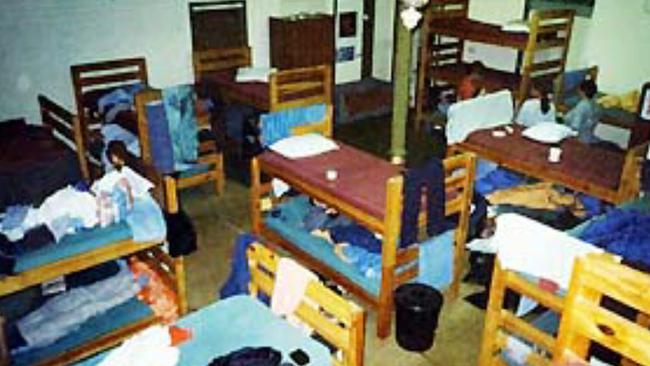

They busted a door in, one that had been screwed shut to turn a room into more accommodation. A dorm room.

Watson remembers seeing beds everywhere. Bunks crammed in to a large open room. The ground floor wasn’t burning like the floor above but debris fell around them as they navigated the dormitory.

Then, a crash. They didn’t see it fall. But the burning bundle landed on the floor in the room with them.

“There’s three or four of us in the room and there was a small ceiling collapse,” Watson said.

“And that was the first deceased person we came across. They actually fell through the ceiling.

“That just really rammed home the fact that we had lost people inside the building and how bad the fire was on the second floor.

“It had burnt through … and the floor had started falling through the pressed metal ceiling on the ground floor.”

They threw wet blankets on the man. There hadn’t been much more they could do for him – he was already dead – but they could stop him burning.

Fire fighters were by then bringing the blaze under control. They got hoses to elevated positions and fought it on the upper level from the outside.

On the ground floor, Watson and his team moved through the dorm room to the foyer and office areas.

In the office they pulled the fire safety plan from the wall. They searched for – and found – the register of occupants.

A list of names. Young people. Kids on adventures, far from home, far from their families.

WHO LIT THIS FIRE?

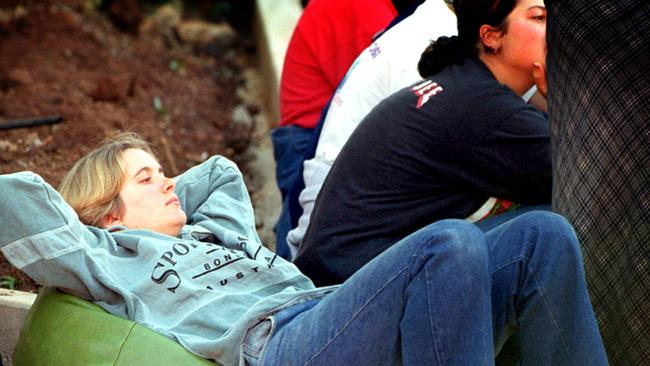

SERGEANT Fay and his team spoke to blanket clad backpackers one by one. Some had escaped in their underwear.

Who were you with, they asked. Where are they now?

A young man, a backpacker, approached.

“This is not an accident,” he said. “This has been deliberately lit.”

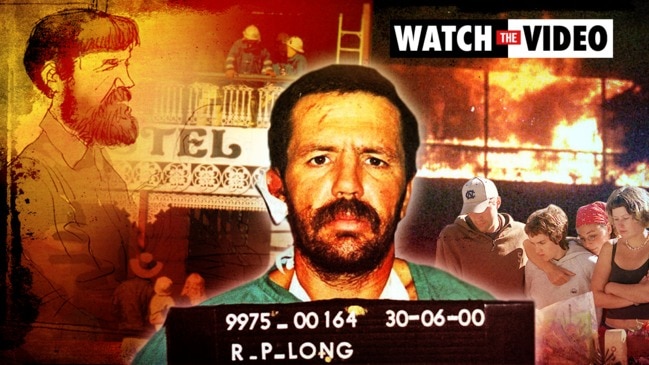

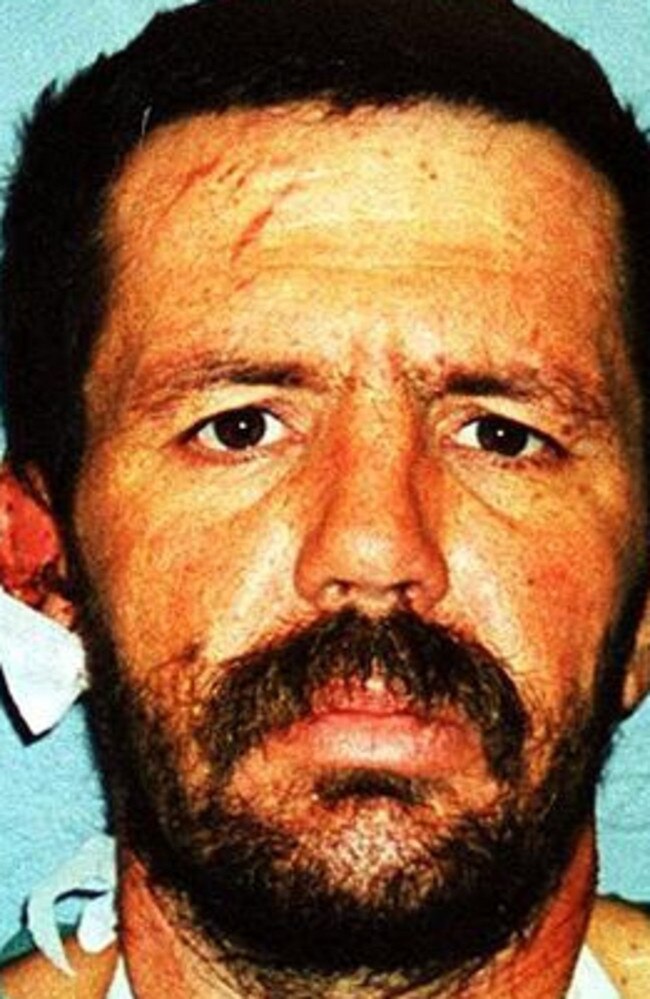

Then, a name. Robert Long.

They knew him. Police had checked him out when he’d arrived in town. He had a long criminal history.

They knew he’d had a beef with the hostel. He’d left owing money. He’d been leaving suicide notes around town.

“We basically had to try and task (two local officers) to try and track this fellow down,” Sgt Fay said.

“Obviously he wasn’t at the immediate scene. Is he here or not? Is he in the building?

“I remember one of the officers had mentioned his name … before the fire.

“Obviously when there’s someone new in town, we’ll check their details and see if they’re wanted … see what form they’d had. Often you get people come into town and they’re wanted on warrants. You can see that police in other areas have had trouble with them, so you keep an eye on them.

“The sooner you can identify those people, the sooner you can get on top of managing people in your town.”

Long didn’t just have a criminal history. He had a history of lighting fires.

“Pretty much any time he had a disagreement with somebody, I think he’d burn their caravan or burnt their car … or whatever it might have been. But that’s turned out to be his MO,” Sgt Fay said.

THE REALISATION OF DEADLY INFERNO

BILL Trevor was supposed to be going to Brisbane. He’d had plans to meet with the heritage council to discuss shifting the town clock from its current location, just across the road from the hostel.

But when the Isis mayor was called at 2.30am about a fire at the Palace, he felt uneasy. He decided to have a look for himself. He’d make sure all was OK, then drive to Bundaberg and hop on a plane.

“When you are the mayor of a small town you know 90 per cent of the people personally,” Trevor said.

“I just had a gut feel that I had to have a look at it first.”

The highway was blocked and Trevor drove around a barricade and to the post office.

It was 5am when he pulled up. The sight in front of him will never leave his mind.

Dozens of people were sitting on the gutter and staring up at the Palace. Their faces looked sad, desperate.

They were young. Just kids. Not much older than his own kids.

“A lot of them were only in their underwear and some had blankets draped around their shoulders,” Trevor said.

“It was smoky, foggy and it was almost if they knew their mates weren’t coming out and that they were willing them to join them on the footpath.”

The sun hadn’t yet risen and Trevor crossed the road where the fire trucks were parked, lights still flashing.

He met Sgt Fay and the firefighters.

“Bill, this is a real bad one,” the policeman told Trevor. They had 20 people missing.

“There were rumours at that stage that it was deliberately lit,” Trevor said.

“We immediately had on our hands the fact that there were so many survivors that had to be looked after.”

They took over the cultural centre across the road. It had a new industrial kitchen. Local avocado farmer Donna Duncan and other town folk came down and began cooking what would become 1400 meals a day.

Trevor stood in the town’s main street taking it all in, this tragedy that was too big for this tiny town.

He wouldn’t learn until later that he knew the man responsible. Long had worked on his farm, picking zucchinis.

When they’d had to downsize pickers because of the heat-dependent crops, Trevor's field boss sacked Long because of his work ethic. And because he was strange. His demeanour and stare had made the women on the farm feel uneasy.

As emergency crews kept working, Trevor began organising care and support for the survivors. For the next six hours the town of Childers was on its own. But help was on the way from Brisbane.

DON’T GO ON THE SECOND FLOOR

WATSON had given the order not to enter the second floor. It was too unsafe.

But the 1997 Thredbo landslide disaster had taught emergency responders valuable lessons.

Some Queensland fire fighters had been put through specialised technical rescue courses off the back of Thredbo.

Watson knew this. He went up the chain and requested a technical rescue crew.

“So that was their very first response to an emergency event,” he said.

“They sent up a team that went through the process of actually shoring up the whole building. So they put a false floor underneath the floor, supported the end walls of the building so the police could actually take over the job.

“I handed the scene over early morning to police as a crime scene and they took it over from that.”

BURNT BODIES OF YOUNG BACKPACKERS

WATSON knew, even before he walked over that false floor, through that burnt out shell, what he would see in room seven of the Childers Palace Backpackers Hostel.

Firefighters had been up ladders to look through windows. Randall had looked. He’d seen the bodies.

“OK,” he’d thought to himself. “That’s what we’ve got.”

Randall hadn’t seen too many burnt bodies at that point. And these were kids. Young people on an adventure. He blocked it out. Went through the checklist of things he needed to do. He did what he’d been trained to do.

But in the months that followed, he’d find himself awake til all hours. Awake again at 4am. Jumpy.

“Certainly it’s one of those memories I’ll never forget,” he said. “There are a few nasty ones like that over a career that are really personal. You try to lock it away a bit.”

Today he knows a lot more about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. As a lieutenant, he’d paid far more attention to how his crew was coping. He hadn’t thought too much about himself.

THEY WERE TRAPPED, THERE WAS NOWHERE FOR THEM TO GO

THE scrutiny that followed such a terrible fire was hard on the heroes who ran into the flames.

Journalists spoke to experts about what firefighters could have done differently. They were criticised for not using equipment they didn’t even have.

Press from all over the world had arrived within a day or two and set up link trucks and satellite dishes on the town green.

They filmed the arrival of a container, a temporary morgue, outside the gutted building. It stayed there for weeks.

“Just alongside the national highway,” Trevor said.

“Once the highway reopened you could see people pulling up at the traffic lights next to the Palace and their head jerked to the left and they’d say: ‘Oh that’s where it is’.”

Coroner Michael Halliday arrived in town and Watson took him from room to room. The ground floor, where Long had lit his fire. The dormitory. The office. The atrium. Fifteen bodies.

“Disbelief,” Watson said of the death toll.

“Was he the most clever arsonist? Because he couldn’t have lit the fire in a better place, or worse place, to create the devastation because of the design of the building. I don’t know if he’s a clever criminal or not, but the outcome and the carnage that he created was horrific.”

The fire, lit in the TV room, had spread to the adjacent atrium – a natural funnel that channelled super-hot air until the top floor exploded.

And that’s where Watson took the coroner. Upstairs. A series of rooms crowded by bunks. Beds blocking doors. Bars on windows.

They walked over charred and blackened floors. Past the body of Hui-Kyong Lee, who was supposed to be learning to swim the next day, who had been holding Sarah Mahoney’s hand as they tried to crawl to safety.

Sarah had got out.

Past the body of Kelly Slarke, whose twin sister Stacey died in that building with her. And past Dutch woman Joly Van der Velden, who’d loved Australia and its vivid landscapes.

Watson took the coroner into room seven. There were so many bodies. This is where they’d all come to escape the flames.

“That was the most surreal scene that I’ve seen in my life,” Watson said.

“The people in that room. I couldn’t describe it. It was a surreal thing.”

It was the worst thing he’d ever seen. It is still the worst thing he’s ever seen. Nothing has come close.

“It was … the room was reasonably well intact, as in, it was burnt out, but it was not ashes. There were still beds and there were still people in bed,” he said.

“And they’d obviously all gathered in that room trying to get away from the fire.

“I’ve been to a lot of road accidents. They are horrific in themselves. But this was overwhelming. It was a devastating scene.”

Coroner Halliday looked around the room. He looked at the beds, at the bars on the window.

He turned to the senior firefighter, who’d seen plenty, but never this.

“So they were trapped,” the coroner said.

“There was nowhere for them to go.”

THE MIRACLE

THE auxiliary crew from appliance 913 stayed on scene until the following evening. Close to 24 hours on the fireground.

Another crew came to relieve them but they still had work to do. Back to the station where they cleaned the truck, restocked equipment. Got it ready for the next fire.

Richard Randall never did quit firefighting. But the days that followed were hard. The scrutiny. The media. The calls to his home phone from parents, hysterical with grief, wanting to know if their children were alive or dead. They didn’t even realise they were calling the home of a firefighter. Parents from all over the world were ringing any number they could find in Childers.

A year or two later he applied for a full-time position. He still fights fires today. There’s nothing like it, he says. Nothing like that feeling of kicking in a door, rushing in, getting people out, getting people to safety.

Curl Santacatarina, now in his 70s, doesn’t count Childers as the worst thing he’s seen – although it does come close.

He still drives his wife Bev crazy by disappearing to the station to scrub toilets, clean out the engine bays. It’s his second home.

But it also gave him the skills to save her life a few years later. She’d had surgery. Breast cancer. He’d been out on a job. A drunk had walked out in front of a car. It was the early hours of the morning. They’d been lying in bed, talking, neither able to sleep.

He’d asked her a question and she hadn’t replied.

“You right Bev?” he’d asked her. No reply. He’d switched on the light. She was gone. Cardiac arrest.

He’d dragged her off the bed and done CPR until he’d got up the guts to stop long enough to dial triple-0.

The same paramedics who had been with him at the crash got the job.

They’d been at the hospital. They’d commandeered a doctor, bundled him into the ambulance. Much like Santacatarina had commandeered a fire truck all those years ago.

They drove up over the gutter and across his front lawn to get to her. She’d lived.

He’d saved her.

Now, when he thinks about Childers, he remembers going into that office, the heat and smoke around him, and seeing a single goldfish swimming in a bowl. All those people who’d died - and that silly fish had survived.

Geoff Fay is still the officer in charge of Childers police station. He celebrated his 20th anniversary a couple of years ago.

He hadn’t known the town too well when the Palace burnt down. But now he is part of it, part of that town’s history.

John Watson rose up the ranks to become assistant commissioner of the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services before retiring. He still thinks about Childers, about the horror, about the sadness.

He hopes that on this, the 20th anniversary of the worst fire he’s ever seen, people will think about the lives they saved as they remember the lives they lost.

TRACKING LONG

ON June 28, five days after the fire, a tracking dog being led by officers from the Queensland Police Service’s Special Emergency Response Team picked up Robert Long’s scent on the edge of the Old Bruce Highway at Burrum River Bridge, about 30km out of town.

The tracked him to the edge of the riverbank. They tried to arrest him. He struggled. Swung a knife, getting one of the officers in the jaw.

The dog attacked. One of the officers fired his gun. Long ended up with a minor injury to his ear. He’d assessed it differently.

“I’m dying anyway,” he told them. “I started the fire.”

MORE FROM THE SERIES:

- ‘BODIES FELL THROUGH CEILING’: FLASHPOINT OF DEADLY INFERNO

- SEVEN COFFINS OF HEATHROW: MOMENT FAMILY’S NIGHTMARE UNRAVELLED’ (live Friday June 5 at 5pm)

- HOW SUICIDAL MADMAN GOT AWAY WITH KILLING 13 (live Friday June 5 at 7pm)

- ‘I’M DYING ANYWAY’: LONG’S BIZARRE $10 NOTE CONFESSION(live Saturday June 6 at midnight)

- TORTURE, TORMENT AND FANTASY: MAKINGS OF SUICIDAL MADMAN (live Saturday June 6 at noon)

- ‘SNAKY LITTLE BASTARD’: INSIDE LONG’S PRISON LIFE (live Sunday June 7 at midnight)

- DEATHLY SCREAMS, SCRAMBLE FOR LIFE: INSIDE AS PALACE EXPLODED (live Sunday June 7 at noon)

‘AUSSIE MUM’ RISES FROM ASHES FOR TRAUMATISED BACKPACKERS (live Sunday June 7 at noon)

Shock link between UK child killer and Aussie bishop stabbing

The teen who murdered three little girls at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class in England had searched for material on the stabbing of a Sydney bishop.

New law to block legal challenge to AN0M sting

New laws will prevent any legal challenge to one of Australia’s most successful covert stings in organised crime using the encrypted AN0M application.