The eagerness to change the Brownlow Medal but not other Australian football traditions is misguided

STRIPPING the Brownlow Medal of its “fairest” component is one tradition Australian football should not eagerly adopt.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Bone’s beef: Three strikes for policy

- Danger, Cats accept umpire’s call

- Martin on track to dust Brownlow record

- Saint champ’s Brownlow threat

TRADITION in Australian football is blinding.

So the bounce at the start of a game – and after each goal – stays while the umpires will throw the ball everywhere else. This is despite the players preferring the bounce to go and umpires noting their careers would last longer.

But tradition dictates.

“It has always been part of the game,” the traditionalists say, even though the very first games in the 19th century did not start with the bounce. This came in 1891.

The father-son recruiting rule stays regardless of this quirk compromising the AFL draft – and, for now, having no relevance to Gold Coast or Greater Western Sydney. Again there is this fascination with tradition that even some sons do not embrace.

Only the 22 players in a winning grand final team get an AFL premiership medal. Yet the importance of an AFL squad in a marathon campaign to a flag merits every contributor having a premiership medal more than ever before. It is the case with far more treasured sporting awards such as an Olympic medal.

But Australian football tradition demands no change to the term “premiership player”.

And then there is the Brownlow Medal.

Since 1924 the VFL-AFL’s highest individual award – following the same premise of Australian football’s first league-wide player trophy, the Magarey Medal in the SANFL in 1898 – has demanded the umpires acknowledge the “fairest and best” player.

Voting systems have changed. There has been a countback system (1930-1980) and in 1989 the league struck retrospective Brownlows for those players denied the award by the tiebreaker system.

The debate has raged whether the umpires should make way for a panel in the stands, as there is for other trophies such as the Norm Smith Medal for the best-afield in the grand final.

But tradition dictates the “fairest” aspect of the Brownlow be retained regardless who marks the voting slips after each home-and-away game.

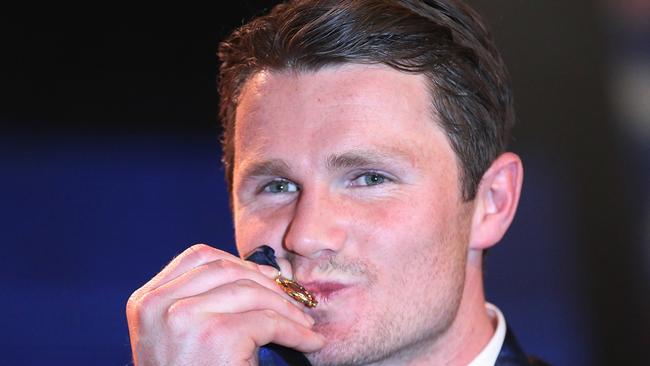

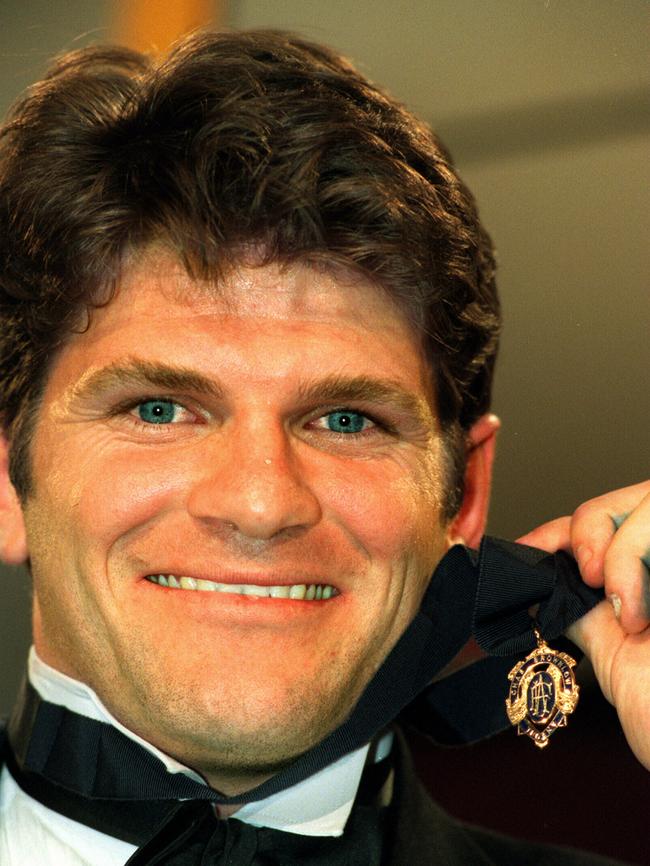

Geelong midfielder Patrick Dangerfield’s one-game ban this week – for his tackle of Carlton ruckman Matthew Kreuzer – puts tradition on the line again. Even though no-one knows if Dangerfield has enough votes to retain the Brownlow Medal, there is now certainty (by his suspension) that he cannot become the first player since Robert Harvey to win consecutive Brownlows (1997-98).

Harvey’s first Brownlow was with tradition dictating the player with the most votes (27-26), Western Bulldogs half-forward Chris Grant, not take home “Chas” because of his one-match suspension (from a report filed from AFL House rather than the umpires).

Tradition holding the AFL to the bounce is silly. Tradition with the father-son rule is contradictory to all the AFL demands with the draft. Tradition with premiership medals is well outdated.

But tradition with the Brownlow Medal does have its merit (more so when clubs still hand their “best-and-fairest” awards to players who even cop bans in their own clubhouses).

Had Dangerfield polled an unbeatable 35 votes to Round 22 and then been banned for one game for striking Will Langford – in reaction to the Hawk kissing him on the cheek in Round 23 – would he merit the Brownlow?

Some traditions are worth protecting.

michelangelo.rucci@news.com.au

Originally published as The eagerness to change the Brownlow Medal but not other Australian football traditions is misguided