Forced adoption: Brisbane mum’s decades-long search for stolen son

More than 50 years after her newborn baby was taken from her in a Brisbane hospital, Lily Arthur is still fighting for justice on forced adoption. Hear how she was reunited with her son.

Southeast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Southeast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

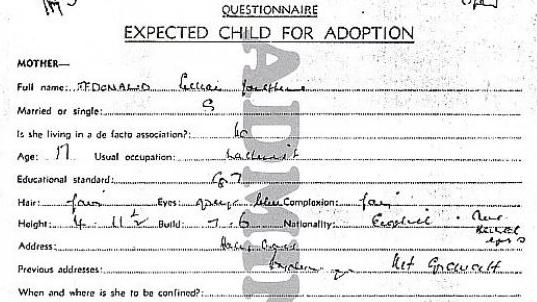

The year was 1967 and Lily Arthur was 16 years old – and six weeks pregnant – when two policemen marched into her home and bedroom in Rocklea.

She said the pair interrogated her about her pregnancy before taking her to a watch-house where she spent the night before facing Children’s Court, charged with ‘being exposed to moral danger’.

For the crime of falling pregnant outside of wedlock, Ms Arthur was committed to “care and control” at Holy Cross Home in Wooloowin – an institution that was, according to the 1999 report of the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions, “for the reception of delinquent girls”.

In Ms Arthur’s words, it was a place “run by the nuns” “where they used to lock the girls up and make them do the bloody washing and everything else like that.”

There, she was “forced to work without pay” until she was discharged in October following the birth of her child.

She was 17 years old and sitting in church when she went into labour.

“When I went into the Royal Brisbane Women’s Hospital, when I gave birth, they had me tied down. And then they took the baby and hid him in the hospital,” she said.

“I never saw him, the whole time I was there. And on the eighth day, a woman from the department came and got my consent off me to adopt my son out ….

“They left me in a position where I didn’t have any choice. I had to sign an adoption consent.”

She said it was only then that she was allowed to see her son. And only for five minutes.

“I had to hold a card up against a nursery window with his name on it and they showed me a baby,” she said.

“I don’t even know if it was mine.”

Ms Arthur said she was immediately sent back to the Home and forced to work. She recalled folding pillow cases in the laundry the very afternoon she gave birth.

Six weeks later she was discharged and living with her parents in Sydney.

It would be another 31 years before Ms Arthur reunited with her son – her search for him only coming to an end after, “by a huge stroke of luck”, she discovered his first name.

“(It) took me another eight years of looking, with only his first name to go by, to eventually find him by scouring 2.5 million names through the electoral roll,” she said.

They reconnected in 1998 and have since shared and an “on-and-off” relationship, which Ms Arthur puts down to her coming into his life “out of the blue”.

He had only learned he was adopted some eight years earlier, when he was 23 years old.

“I haven’t had a great lot to do with him over the years,” Ms Arthur said.

“I think he can’t get his head around how to deal with what he’s found out.

“I think I’m too tired. I’m extremely tired. I’ve given up hope that I’ll ever have any sort of heart-to-heart relationship with him because there’s just that mountain to climb over, to deal with all the emotional stuff, and he doesn’t want to go there.

“I’m still more or less trapped in the outrage of the big picture.”

Ms Arthur said she had been fighting for justice since 1976, when authorities “robbed” her of her son, alongside thousands of other young mothers.

A 2012 Senate Inquiry revealed there were 140,000 to 150,000 total adoptions between 1951 and 1975, and up to 250,000 total adoptions from 1940 to 2012.

And though it is impossible to know the exact number of people who were affected by forced adoptions, the Australian Bureau of Statistics recorded a sharp drop in total adoptions after 1972 – “a time of rapidly changing social attitudes surrounding the plight of young unmarried mothers”.

In 1971-72, 9798 adoptions were recorded. Four years later, this number had halved to 4990 and by 1979-80 it had dropped to one-third. By 1995-96, there were only 668 adoptions recorded in the country.

There are even fewer today, with just 264 adoptions finalised in 2020-21.

What happened to Ms Arthur all those years ago changed the trajectory of her life completely. Now 72 years old, she has been an activist for 25 years and authored a book titled: ‘Dirty Laundry: The crimes a country tried to hide.’

But she fears she and those she advocates for still may not see the action they deserve in their lifetimes.

“It’s the biggest human rights abuse against young women to ever occur in any generation, and no one seems to think that it’s worthwhile to try and fix the damage,” she said.

In the lead-up to the 10th anniversary of former prime minister Julia Gillard’s apology to victims of forced adoption, Ms Arthur has created a change.org petition calling on the federal and state governments to commit to implementing redress schemes for all victims.

“A redress program provides victims with the opportunity to be compensated without having to take prolonged legal action,” she wrote in her petition.

“Victoria has made great progress implementing a redress strategy, and it’s time that all state and territory governments did the same. We also need the federal government to step up by implementing a national redress scheme.”

While financial compensation cannot possibly undo the pain suffered by victims of forced adoption, Ms Arthur said it would at least be a “tangible sign that these people are really, truly sorry”.