Forced adoption Queensland: Victims pushing to change statute of limitations

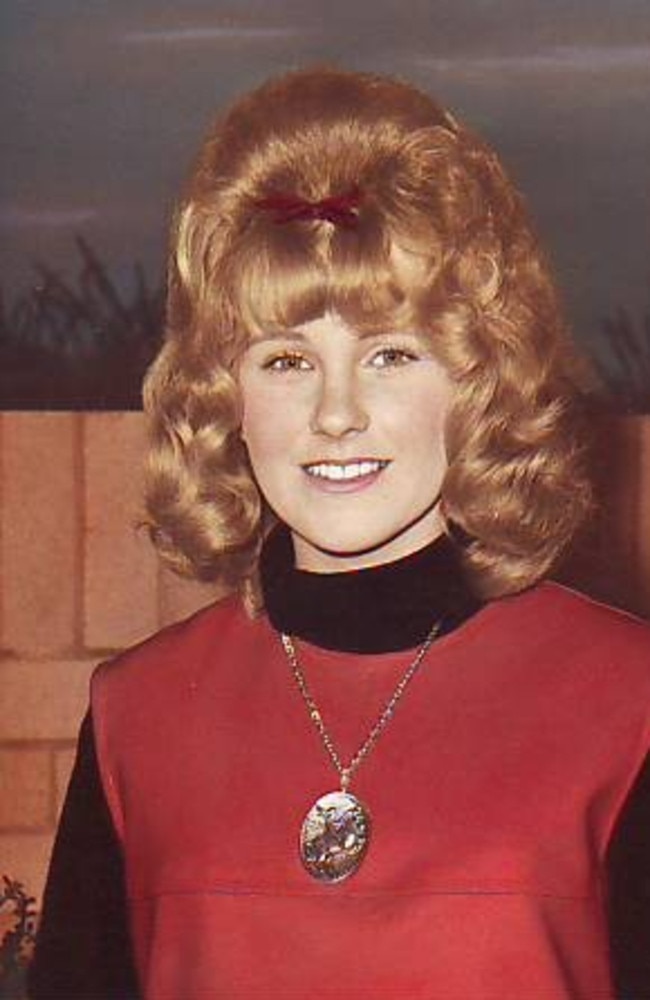

It’s been 58 years, but forced adoption victim “Julie” still remembered the harsh demand as her life was changed forever.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

She was the shamed daughter of a solicitor sent to a home for unmarried women, made to drink castor oil to trigger an early labour to a girl she’d never know who’d be sold to strangers.

“Hand her over.”

It’s been 58 years since Julie (not her real name) was forced to give up her six-day-old daughter to adoption, but the brutal demand still echoes in her mind.

Julie had fallen pregnant at 15 to an older teenager.

To hide the shame of an unmarried pregnancy her parents would lock her in wardrobes and bathrooms, and make her hide her baby bump until it was no longer possible.

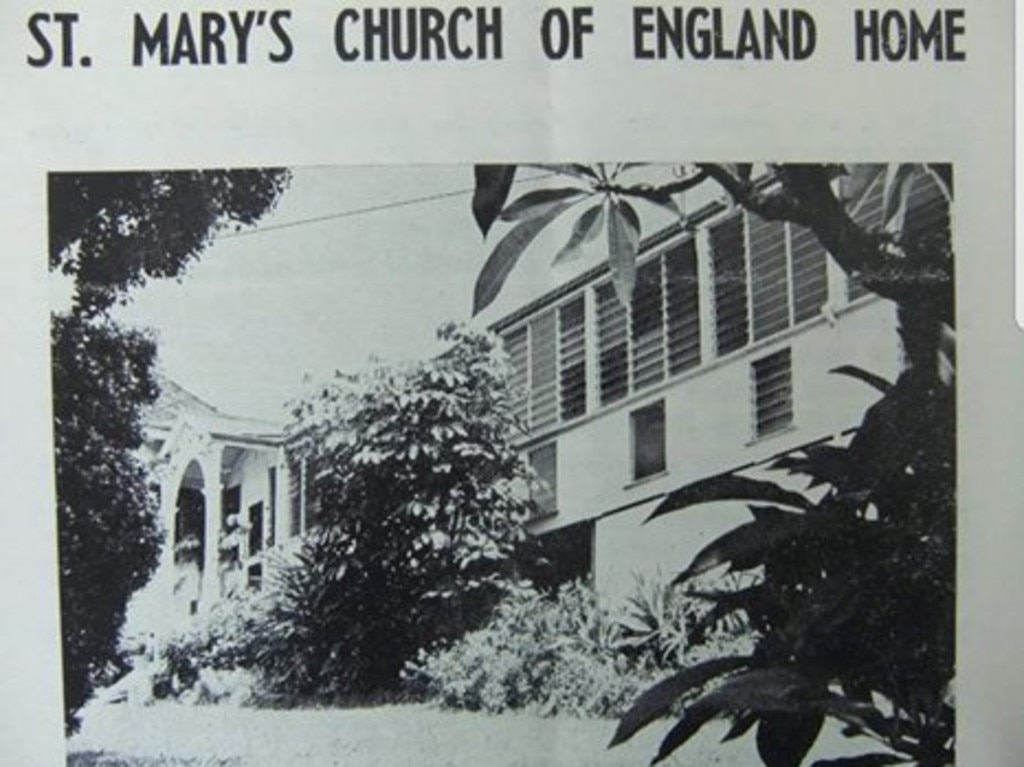

At four months pregnant she arrived at St Mary’s Toowong in Brisbane in 1964 – a “good church home”, her mother called it – where she was housed with 25 other pregnant women.

Dressed in blue and white chequered uniforms, the women would scrub floors on their hands and knees, wash men’s clothes from around the district and received 25c for their work.

They lived on a diet of frankfurts and the Sunday special of baked eggs, mixed with powdered milk and water.

Julie once found a shilling (10c in today’s money) and snuck out of St Mary’s to buy a chocolate bar.

Little did she know the seemingly innocent treat for a pregnant woman with uncontrollable cravings would lead to a premature birth.

She arrived back at St Mary’s to angry staff who placed her on a stool in front of the other women and told to drink the cup of castor oil.

“ ‘You’re going to get punished.’ That’s what they told me before they made me drink it,” Julie said.

Six hours later she woke “freezing” in an old Queenslander at Ashgrove, turned into a private hospital, with no memory of the actual birth.

Julie stayed at the hospital for a week where she was placed in a room with other “wicked” girls before the traumatic “handover” date came and her daughter was taken from her.

“I still remember the look in her eyes,” Julie said about the lack of empathy shown from the mother who adopted her daughter.

“The matron introduced us and then forced me to hand her over.

“After they left with my baby, she made me go to the window to watch them leave.”

A self-described naive child who was not legally old enough to sign documents, Julie had to sign the papers a week before she gave birth.

She claimed staff at St Mary’s would request cash payments – about $1500 in today’s coin – from the adopting parents for the babies. Money she was convinced the staff members pocketed.

Julie, and fellow others who endured forced adoptions want action from the state government to change the statute of limitations so victims of the heinous policy can claim compensation.

Shine Lawyers abuse law practice leader Jake Gardiner said the firm had lobbied Crown law in relation to individual cases, pleading the statute of limitations to be dropped.

Mr Gardiner said the team was in process of compiling formal submissions from 13 victims to send to the government.

“It is time for the government to finally do the right thing by these women by removing time limits on legal claims, as they have done for victims of childhood sexual abuse,” Mr Gardiner said.

“These women and their children have been victims of the most atrocious practices, and endured decades of pain and trauma through no fault of their own.”

A spokeswoman for the Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs said it had received several inquiries regarding redress due to former forced adoption practises.

She said the government had noted these contacts as a matter for consideration and that the conversations with victims were ongoing.

“The state government provides funding for post-adoption support services to help people impacted by past forced adoption practices,” she said.

“The department also continues to work with key representatives from post-adoption stakeholder groups to ensure practices of the past are not repeated.”

Now 75, Julie is still visibly haunted by the trauma from more than half a century ago.

The rushed pregnancy made her unable to have another child while she said no apology or compensation would help numb her pain.