Forced adoption Qld: Victims in push to change statute of limitations

A mother strapped to a bed to birth a son who would be taken from her. A baby sold into adoption for £5. Families separated for 44 years. This is the dark history of Queensland’s forced adoptions.

QLD Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

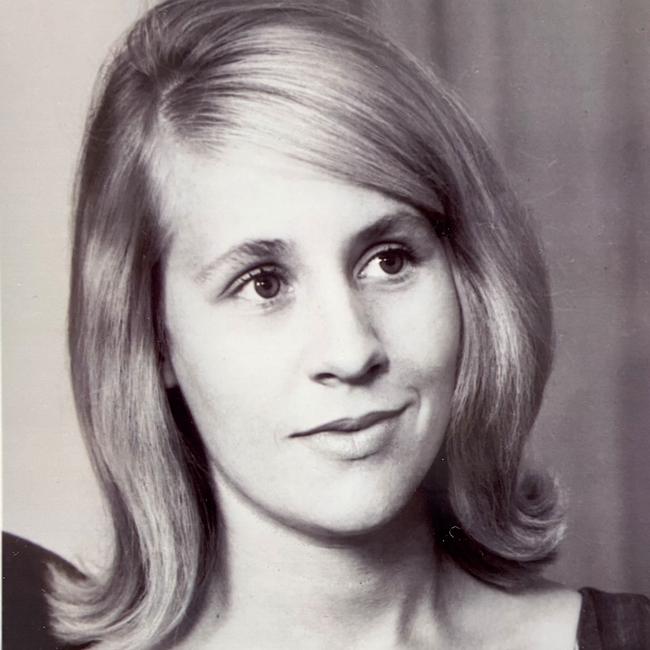

Shackled to the bed and injected with drugs, Janice Benson would wake up without her baby bump – and without her baby.

She would not lay eyes on her little boy for 33 years.

For Lesley Mitchell, it was 44 years before she first saw her son after he was walked out of the hospital birthing suite in the arms of a stranger.

A sheet partition, put up by Catholic nuns at a religious Queensland hospital, would cruelly stop her from seeing the baby she had birthed.

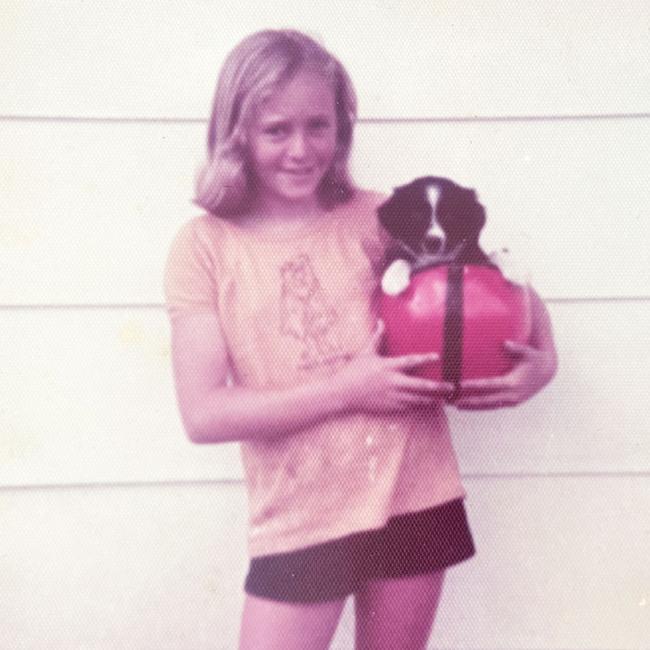

For Kerri Saint, who was sold to her adoptive parents for £5, life would deliver a series of blows while growing up as a labourer, sent to work in a charcoal pit from age five.

She would endure serious abuse throughout her childhood.

All three women would struggle with the impacts of forced adoption and, despite legal threats and welfare penalties, would decades later find the courage to reunite with their family members.

These women are some of a legion of parents and children who form part of Australia’s dark history of forced adoptions.

Now, some 60 years later, they are banding together to hold to account the charities, churches, institutions and individuals who wronged them.

But first, they need the law to change.

Under the statute of limitations, people subjected to forced adoption cannot pursue compensation for complaints more than three years after the wrongdoing occurred.

A Senate inquiry into former forced adoption policies estimated there were 140,000 to 150,000 total adoptions in the years between 1951 and 1975, however the report, released in 2012, concedes the actual number is much higher.

The inquiry recommended that “formal apologies should always be accompanied by undertakings to take concrete actions that offer appropriate redress for past mistakes”.

It recommended governments responsible for adoption activities establish mechanisms that allow complaints to be heard, and where evidence of wrongdoing is established, ensure redress is available.

“Accessing grievance mechanisms should not be conditional on waiving any right to legal action,” the report said.

The women called for their ordeals to be referred to as what they are – crimes.

“The things they did to us have names,” Ms Benson said.

“When they took my baby from inside my body while I was unconscious, that is rape.

“When they stole my child and gave it to someone without my consent, that is kidnapping. These are crimes that no one has ever paid for.

“They happened and no one does anything about it.”

Queensland’s Attorney-General Shannon Fentiman has this morning said the government is currently looking at a redress for Queensland victims of forced adoption.

“Absolutely that’s something the government will look at and of course we have had an apology to those Queenslanders who have experienced forced adoption,” she said.

“Having been once the Child Safety Minister and the minister responsible for that portfolio area - I have met with a number of victims of forced adoption and I understand the pain they have been through and I understand that is something the minister and department are now looking at.”

When asked whether those victims should receive compensation, Ms Fentiman said “I understand that is something that the minister is looking at”.

DISAPPROVING FAMILY

Ms Benson was 20, engaged and in love when she fell pregnant unexpectedly.

She intended to raise her child with her partner, who was from an educated immigrant Russian family.

But Ms Benson’s well-known Brisbane family did not approve of the arrangement and she was sent to the Anglican Church’s Carramar Home for Delinquent Girls in Sydney’s leafy Turramurra.

Ms Benson, a teacher, says the home threatened her with police action if she dared keep her son after birth.

“What am I going to tell these people that I have for your baby, what am I going to say to them?” Ms Benson would be asked.

“Tell them they can have someone else’s baby, they don’t need my baby. It’s my baby,” Ms Benson would reply.

When it was time to deliver her baby, Ms Benson, now 80, told nurses at Hornsby Hospital “my son is not up for adoption, he’s coming with me”.

“Then … I was drugged,” she said.

Ms Benson’s hands were shackled to the sides of the bed with a leather strap. The nurse told her the restraints were “just a precaution”.

“I thought ‘they’re going to kill me, they’re not going to let me get out of here because I made a nuisance of myself saying my son’s not for adoption’,” Ms Benson said.

“I was unconscious for the last hour of my son’s birth. I didn’t see him. I didn’t know he was born. And I looked for him down the end of my bed. He wasn’t there. No one was.”

A DIRTY SECRET

In 1972, Lesley Mitchell was told to keep her “dirty secret” to herself when she found she had fallen pregnant.

“It was this dirty secret that we weren’t allowed to talk about,” Ms Mitchell said. “We were told it was disgusting … there was a lot of shame.”

When birthing her son, who she later learned was named Shane, a nurse would say of Ms Mitchell’s body “oh well, let her rip”.

“The nursing staff were awful, oh my god they were horrible,” Ms Mitchell said.

Like Ms Benson, Ms Mitchell never laid eyes on her baby. After she was given an unauthorised epidural, a sheet was placed in front of her.

“I heard him cry as he was taken out of the room and that was it. He was gone,” she said.

A HORRIFIC START

For Kerri Saint, tragically, life as an adopted person would be “pretty horrific”.

“My upbringing was child slave labour – there was a lot of mental, physical and sexual abuse,” she said.

“Some of the abuse bordered on torture.”

Ms Saint lived in a tent and worked in a charcoal pit for much of her childhood.

“Growing up, I was always made to feel that I had to be ashamed of my mother and ashamed of how I came into the world,” Ms Saint said.

It would not be until Ms Saint went to a specialist for back pain as an adult that the trauma was realised.

“The specialist gasped, looked at me and said ‘all right love, you’ve either been in a car accident or you’ve been bashed’ …

“And all I could say was that I had not been in a car accident.”

Ms Saint’s spine had been crushed. In the specialist’s opinion, there had to have been days when Ms Saint would have been unable to walk.

“I’ve blocked that trauma from my memory,” she said.

THE FIGHT

These women are angry and want their voices to be heard – for the statute to be lifted.

It’s not just about financial compensation, but about holding those who committed the illegal acts to account.

“I think it’s time for all those who stole babies to acknowledge their crimes and to apologise to the women whose babies were taken from them,” Ms Benson said.

Ms Benson and Ms Mitchell said they had not known how to fight a system designed to keep their children away.

“I had no clue that I could say anything against what was happening,” Ms Mitchell said.

“The statute of limitations needs to be lifted and it needs to be advised because there’s so many aspects of what was wrong with (what happened).”

For Ms Saint, the system did what it was meant to – keep her from her mother.

“I was told that my mother was 16 and had died while giving birth to me,” she said.

“We’ve had all these apologies and other people who have suffered abuse get compensation, but not people of forced adoption.”