WHAT dreams did she have, this young mother from a small country town, as she sat in her run-down rented Queenslander with its view of a petrol station in inner-Brisbane?

Had she envisaged this, the worker’s cottage with the slumped fence and cracked window out front, the abusive and philandering husband, the convicted criminals breezing in and out of the house, when as a child she performed a sketch in a Sunday School concert called A Wedding in Fairy Land?

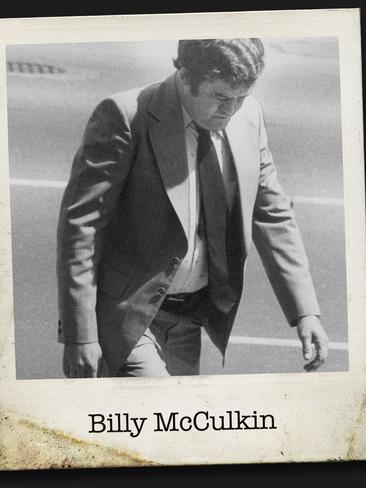

By early 1973, Barbara May McCulkin had been married to Robert William “Billy” McCulkin for almost 13 years, and life with him and their two children – Vicki, 12, and Barbara Leanne, 10 – in the house at 6 Dorchester St, Highgate Hill, was far from fairyland.

CHAPTER 2: Mass murder at Whiskey Au Go Go

CHAPTER 3: The night a family vanished

CHAPTER 4: The murder of Mrs X and her children

CHAPTER 5: Return to Dorchester Street

How could she have seen this, coming from a good country family, having grown up in a sprawling Queenslander not far from the Mary River in Maryborough, 255km north of Brisbane? Here she sat, already feeling old and neglected, at her sewing machine, making her own and her daughters’ clothes while her husband was in town, drinking heavily with workmates, criminal associates and corrupt coppers.

The only star in Barbara McCulkin’s firmament at the beginning of 1973 was the bulb of her sewing machine. Then 33, Barbara was a good mother with an uncertain future.

Billy had rarely seen full-time work since his time in the Royal Australian Navy in the late 1950s and into the 1960s, and money was always tight.

They had no car (Billy McCulkin professed that he couldn’t drive), so Barbara and the children’s social life was restricted to public transport and the kindness of friends with a vehicle.

Since 1971 she had worked at the Milky Way snack bar in the Brisbane CBD, and had struck up a good friendship with her co-worker Ellen Gilbert.

And it was in Gilbert she confided about her deteriorating relationship with Billy McCulkin, 32.

“Mrs McCulkin informed me that her marital relationship was not normal and that her husband came and went at will from their place of residence and he boasted to her of his conquests with other women,” Gilbert would later reflect.

“(Barbara) informed me that her husband had beaten her and that she had not been able to attend work as a result of the beating received from him.”

On one occasion he bruised her arm and broke all the crockery in the kitchen. That night she took her daughters and stayed with Mrs Gilbert.

McCulkin, drunk, would tell Barbara about his sex life outside of their marriage. She knew that he had fathered a child with some “Russian” woman. He had also slept with one of Barbara’s close friends. That time she unsuccessfully tried to kill herself with an overdose of sleeping pills.

As for Billy – just over five foot six inches tall, with brown wavy hair and green eyes – he had always been a roustabout. His nose had been broken so many times in fights that a detective would later call it “Billy’s east-west nose”.

In his Record of Service with the Navy’s Strategic Reserve, he listed his profession as “storeman and packer”. He joined eight days after he turned 18 in March 1957. He saw service on various vessels – HMAS Tobruk, Sydney and Penguin – before marrying Barbara in June 1960. She was four months pregnant with their first child, Vicki, who was born in Sydney on November 9 of that same year. Billy took two weeks’ leave for the occasion.

Barbara Leanne was born on June 26, 1962, when Billy McCulkin was based at the HMAS Albatross, the RAN’s air base near Nowra, south of Sydney.

By the end of that year, McCulkin parted ways with the Navy and began kicking around Sydney. In 1966, he temporarily separated from Barbara.

“Why does anyone leave their wife, because they’re incompatible or far fields are green, or something,” he later said of that period in his life.

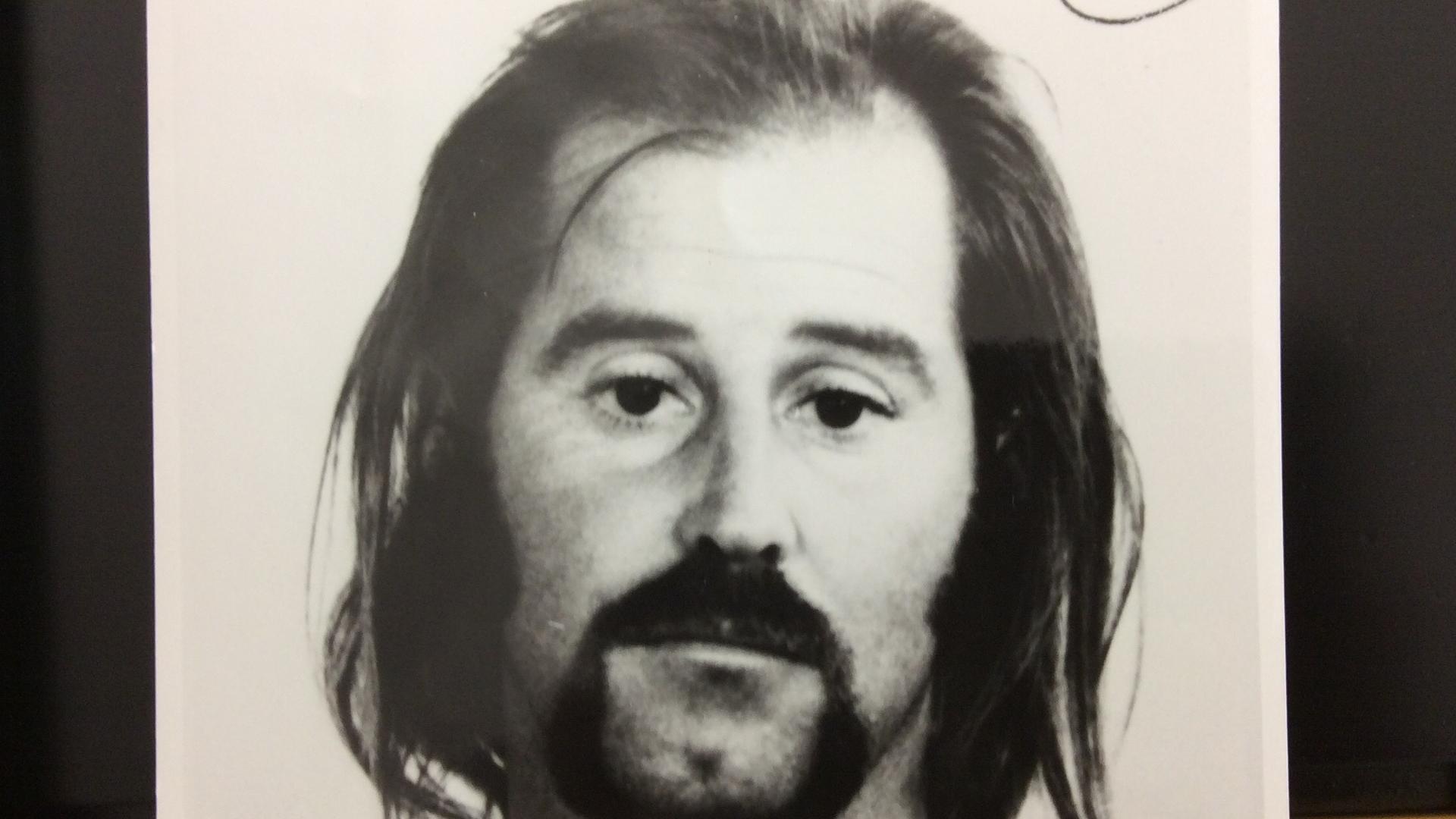

It was in 1966, too, that he met and started hanging out with another expatriate Queenslander, Vincent O’Dempsey of Warwick, 130km south-west of Brisbane.

O’Dempsey had been raised by a respectable Catholic family. His father Tom was a stock and real estate auctioneer, and he had brothers who entered the priesthood. O’Dempsey’s parents both attended mass on a daily basis.

He went to the local Christian Brothers college where he was seen as a quiet boy who never looked for trouble. One fellow student claimed that whenever O’Dempsey was caned by the Christian Brothers, he never flinched or said a word, and was often seen smiling at the punishment that was meted out to him.

In his later teens, however, he developed some behavioural irregularities. With another boy he would bag stray cats around town and knife them to death “through the bag”, according to one police officer who investigated O’Dempsey.

He was diagnosed in a Toowoomba Hospital as being in a “psychopathic state with schizoid tendencies”, and was intermittently institutionalised.

Despite this, a teenage O’Dempsey earned a name for himself in the boxing ring. Training out of the Warwick Athletics Club, he won numerous regional bouts.

His other interests included breeding hard-feather bantam chickens. At Warwick’s 87th annual show in 1954 he won second prize in the black Pekin bantam category and first place in the hen or pullet section.

This hobby appeared wildly at odds with the man who, when shooting the breeze at a local Warwick pool hall, was asked about the best way to get “girls”. One local allegedly heard O’Dempsey say that procurement was easy, you just “walk up behind them with a rag soaked in chloroform and hold it over their nose, then you can do what you like with them”.

In his mid-to-late-teens, O’Dempsey presented as a peculiar, dichotomous, multi-faceted and complex character. A fastidious breeder of prize-winning poultry. A boxer. A big thinker who was fond of quoting the Bible. A killer of small animals. And a man who, for whatever reason, had an absolute pathological hatred of police.

In the early 1960s, O’Dempsey had been working on the construction of the Leslie Dam near Warwick when he befriended a co-worker named Raymond Vincent “Tommy” Allen.

Allen, a flamboyant dresser (he was often seen around town in leopard-skin pants), assisted O’Dempsey in the burglary and arson of the Pigott and Co department store in Toowoomba.

When he was picked up by police and questioned in 1964 he admitted to the crime and agreed to testify against O’Dempsey in court. Allen vanished and was simply listed as a missing person and the charges against O’Dempsey were dropped.

Shortly after, when O’Dempsey met McCulkin in Sydney, he was living off the earnings of a prostitute who worked out of the Rex Hotel in seedy Kings Cross. The Rex had also been the former playground of the notorious Brisbane prostitute and madam Shirley Margaret Brifman.

They were a curious pair. McCulkin was short, stocky and drank too much. O’Dempsey imbibed very little and was extremely conscious of his diet.

According to sources close to O’Dempsey, however, he had developed a reputation in Sydney as a feared “gunman”, much like the Sydney gangster Stewart John Regan, who would make headlines in the early 1970s and was acquainted with O’Dempsey.

At some point after 1966, O’Dempsey hooked up again with McCulkin in Brisbane and both were arrested for attempting to steal a safe from the Waltons department store in Fortitude Valley. (The word was that they had been “dogged” or dobbed into the police by local weapons dealer and tattooist Billy Phillips Snr.)

O’Dempsey was given five years for the robbery and possession of a concealable handgun.

Still, a friendship had been forged, and the two men would reunite, with catastrophic consequences.

SMALL FIRES

When O’Dempsey was released from Boggo Road Goal in Brisbane’s Dutton Park – just a couple of kilometres south-west of Highgate Hill – in December 1970, he went to stay with McCulkin at his newly rented property in Dorchester St.

McCulkin got him a job at Queensland criminal identity Paul Meade’s “mock auction” shop in Queen St, the city. Mock auctions were a scam that stemmed back to the Victorian era, where criminal associates of those running the auctions would act as fellow customers, purchasing superior goods at bargain prices. The auctioneer would then win the trust of gullible buyers and sell them inferior or faulty goods at inflated prices.

McCulkin would later tell police he worked “wrapping things” with O’Dempsey at Meade’s auctions. O’Dempsey in fact acted as both security guard and spruiker, enticing pedestrians to come into the auctions.

O’Dempsey stayed at 6 Dorchester St for about six weeks and was the model house guest. He used to go to bed early and he kept to himself.

Occasionally he would drink with McCulkin at the Lands Office Hotel, a hive of local and interstate criminals and corrupt police.

Within weeks O’Dempsey secured his own flat in Harcourt St, New Farm, but he still stayed in touch with McCulkin, dropping into Dorchester St to offer racing tips.

McCulkin later offered a description of O’Dempsey as a man who took “short quick steps like a woman”; that he held one arm in front of himself with his arm bent at right angles when talking; that he kept fit and did not smoke; that he had an intense interest in guns, particularly sawn-off shotguns; that he was in the army and topped the class in ballistics; that he was colour blind; that he was hard to frighten, methodical, and tight with money; that he didn’t like the sunlight because he was fair-skinned and burnt easily; and that he had a tattoo of Saint George and the Dragon on his chest, on his back and both legs.

He shared one trait with McCulkin. Both had tattoos of mice on their penises. It was why McCulkin was referred to as “The Mouse”.

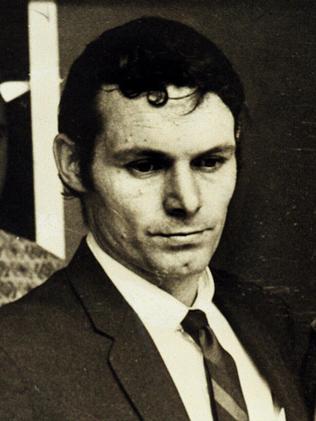

While in prison in the late 1960s, O’Dempsey met a young criminal and convicted rapist, Garry Reginald “Shorty” Dubois, from Brisbane.

Dubois, in turn, was an associate of a group informally known as the “Clockwork Orange Gang”, a group of hoods from Brisbane’s northside that included Peter “The Three” Hall, Tommy Hamilton, Keith Meredith and Doug Meredith. On occasion, Tommy Hamilton, a redhead, was nicknamed “Clockwork Orange”. Some of the gang had gone to school together, others knew each other as childhood neighbours in the suburbs of Chermside, Wavell Heights and Geebung.

Their hero was another local – John Andrew Stuart – who earned his reputation by stabbing a man in the Valley when he was a teenager. Stuart was known to carry a knife, and later a gun. He would be in and out of psychiatric and juvenile institutions, such as the notorious Westbrook, and prison for much of his life.

As for the Clockwork Orange Gang, their activities, by the early 1970s, involved little more than break and entering and indulging in drugs, mainly marijuana and LSD.

“Vince and Shorty were friends,” Hall would later tell police.

“They had been to prison together early on when Shorty was in his late teens.

“I noticed Vince seemed to have a hold over Short, and what Vince said Shorty would agree to. Vince was a bit older than us and was a solo kind of bloke, we knew him but he was not part of our crew.

“I knew he was someone who carried a handgun at various times and he was generally considered as a dangerous man that was not to be messed with.”

Billy McCulkin was similarly entranced by O’Dempsey and was always talking about him, even to Detective Basil Hicks. McCulkin was an occasional informant to Hicks.

“At one point he (Billy) was SP betting from the Lands Office and O’Dempsey may have been involved,” Hicks later said.

“But he (Billy) went on quite a bit about … talking about him, what he’s capable of doing. He talked about he’d heard he’d murdered people.”

By early 1973, another friend of McCulkin paid a surprise visit to Dorchester St. It was John Andrew Stuart, on bail after a custodial sentence in NSW.

The hyperactive and hyper-violent Stuart was telling stories about how Sydney gangsters were set to instigate a comprehensive extortion racket over Brisbane nightclubs. If the clubs didn’t comply, they’d be torched. In fact, Stuart said, they had already chosen a club called the Whiskey Au Go Go on St Paul’s Tce, Fortitude Valley, as an initial target. It would show how serious this southern push really was.

Stuart told a similar story to Detective Basil Hicks, who had known him since he was a troubled teenager, and local tabloid reporter Brian “The Eagle” Bolton.

Bolton sensed a good story and began quoting Stuart in inflammatory stories about the Sydney push for The Sunday Sun.

Then some small incidents occurred in Brisbane that on the surface seemed to bear out Stuart’s wild allegations.

In early January two arson attempts were made on Chequers, a salubrious nightclub in Elizabeth St, the city, owned by brothers Ken and Brian Little. The Littles also owned the Whiskey Au Go Go.

Both Chequers and the Whiskey had gone into liquidation in December 1972 amid unproven allegations of staff rorting and mismanagement.

Then in the early hours of Wednesday, January 17, Fortitude Valley café Alice’s Café and Coffee Lounge went up in flames. Alice’s – an erstwhile miniature nightclub that was popular with Brisbane’s gay community – was owned by businessman John Hannay. He also managed the Whiskey Au Go Go. It was in Alice’s that Hannay kept the Whiskey’s financial records.

Just four weeks later, Stuart’s prophecy seemed on the money.

Brisbane woke to the news that the Torino Restaurant and Nightclub in Ann St had been bombed.

It was mid-evening on Sunday, February 25, when the club – run by brothers Frank and Tony Ponticello – exploded into flames.

Police suspected a bomb, given the extent of the damage. Windows were blown out into the street. The ground-floor club, empty at the time, was extensively damaged.

Detectives were puzzled by the bombing. The blast seemed disproportionate to the space being targeted. It appeared the perpetrators may have used a combination of gelignite, petrol and the building’s gas main. The Ponticello brothers told police they knew nobody who had a grudge against them. Neither the Ponticello brothers or John Hannay have ever been implicated in the crimes.

Decades later, Clockwork Orange Gang member Peter Hall confessed to the crime in documents ultimately tendered in court.

He said he and the gang had been seconded by Vincent O’Dempsey to bomb Torino.

“We were paid to set the place alight and we were told it was arranged by the owners of the club,” Hall said in a police witness statement in the trial of Garry “Shorty” Dubois in late 2016 for the murders of Vicki and Leanne McCulkin and the manslaughter of Barbara McCulkin.

“The deal was organised by Vince O’Dempsey through Shorty.

“We were told that it was an insurance job and we were paid $500, which was split four ways.”

He said they didn’t know what they were doing and nearly blew themselves up.

“That was our first and only big job,” Hall admitted.

“This was a big deal for us. Up until that point we were just break and enter people, but it was good money and we got quite a buzz or an adrenalin hit out of it….”

No one has ever been charged in relation to the bombing.

Over in Dorchester St, Barbara McCulkin had for some weeks been picking up information about the impending “fires” through the rogue’s gallery of criminals visiting her husband, Billy. The house was full of chatter about the arson jobs and Stuart’s claims that Sydney bigshots were behind the string of fires. Even Vicki and Leanne were piecing together snippets of information they heard in conversations in the house in those early months of the year.

According to sources, Vicki was sharing stories about the fires with one of the children of Billy Phillips Snr. The Phillips’ lived directly behind the McCulkins and shared a gate on the back fence; an escape route of sorts, when needed, between the two families.

Barbara continued to work at the Milky Way café despite all this mayhem around her and cryptically said to her workmate Ellen Gilbert about the Torino bombing: “I’ll tell you something funny about that one day.”

But nothing prepared Barbara McCulkin for the morning of March 8, 1973.

If the weary mother-of-two had been standing on her back landing at Dorchester Tce just after 2am that day and she had looked across the city towards Fortitude Valley, just behind the Story Bridge, she would have seen a smudge of fire in the darkness.

It was the Whiskey ablaze, and that firebombing would claim 15 innocent victims.

By the time Barbara awoke that day and prepared breakfast for the children and got them ready for school, the bodies had been laid out in a carpark beside the club and the process of identifying the victims was underway.

And when she was to hear the news of the deadly blaze proper, with all the information she’d picked up over the past weeks at 6 Dorchester St, she would enter a blind panic.

His first response to the tragedy was: “Oh my God, they did it.”

CHAPTER 2: Mass murder at Whiskey Au Go Go

CHAPTER 3: The night a family vanished

‘Prisoners in their own homes’: Grim price of drive-by shootings

A victim’s advocate has called for harsher sentencing for contract shootings as the fear invoked by random attacks has gripped some Sydney suburbs. See the hot spots on our interactive map.

Who Owns Tassie’s farms: Biggest investors, landholders named

An annual investigation can reveal Tasmania has been a key destination for capital in the race to invest in Aussie agriculture. See the full list.